Successful Studying

Foundations, strategies and reflections for a self-directed, sustainable and effective academic journey

Summary [made with AI]

Note: This summary was produced with AI support, then reviewed and approved.

- Studying means taking responsibility, co-creating actively, and using digital tools mindfully. Its foundation is teaching-learning relationships on equal footing, with respect and openness.

- Higher education differs from school or further education. A degree programme integrates research, reflection, personal development, and trains the ability for lifelong learning.

- Core elements are freedom, responsibility, and personal growth. A university is not only a place for knowledge transfer, but also a platform for exchange, civic participation, and critical thinking.

- Lecturers act as learning guides. Trust, respect, and open communication shape successful teaching-learning relationships and strengthen motivation and self-confidence.

- Learning arises from a balance between support and challenge. Resilience, independence, and reflection grow when both dimensions work together.

- Diversity is a strength. Inclusive language, mindfulness, and respectful interaction create safe spaces and promote collaboration in diverse groups.

- Digital support is helpful but does not replace critical thinking. Study time develops judgement, self-reflection, creativity, and the ability to engage in discourse.

- Attendance and personal interaction create resonance-spaces that deepen knowledge, build a sense of belonging, and grow networks.

- Shared responsibility, respect, reliability, empathy, punctuality, and community spirit shape the culture of communication.

- Study success depends on time and energy management. A programme requires about **750 hours** of work per semester (full-time or part-time). Most of this must be invested in self-study.

- Motivation, stress management, and a healthy work-study-life balance are keys to resilience. The university offers support services that can help in exceptional pressure situations.

- Effective learning requires active processing of course content, regular revision, multimodal approaches, practical application, a constructive error culture, social learning, and reflection.

- Notes and annotations make thinking visible, structure content, and ease exam preparation. They also help to develop and retain competences over the long term.

- Artificial intelligence can support, but it does not replace independent research. Transparency, critical evaluation, and supplementing with one’s own analysis are essential.

Topics & Content

- 1 Getting Started - Understanding Your Learning Environment

- 1.1 University is not school - how studying really works

- Checklist: Preparations for Starting Your Studies

- 1.2 Studying Combines Research & Reflection - More Than Professional & Training or Vocational Education

- 1.3 What Studying Means - Freedom, Responsibility, Personal Growth

- 1.4 Learning is Relational - Teachers as Learning Companions

- 1.5 Encouragement & Challenge - What is Expected

- 1.6 Learning Together - Why Diversity is a Strength

- Awareness as Attitude and Practice

- 1.7 Digital Support - Recognising Opportunities, Taking Responsibility

- 1.8 Presence & Exchange - Creating Resonance Spaces, Building Connections

- 2 Five Features of Your Study Programme

- 3 Netiquette in Academic Settings - Taking Shared Responsibility

- 3.1 Writing effective emails - clear, polite and to the point

- 3.2 Showing up online - seen, heard and prepared

- 3.3 Being present in class - punctual, focused, involved

- 3.4 Submitting requests - complete, structured, on time

- 3.5 Succeeding in exams - fair effort, smart strategies

- 3.6 Dealing with conflict - stay calm, stay kind, seek solutions

- 4 Planning & Managing Your Studies - Organise Time, Shape Success

- 4.1 Planning Study Time - Realistic, Self-Directed, Reflective

- Energy instead of Time Management

- Prioritising Energy and Time

- 4.2 Shaping Independent Learning - Active, Goal-Oriented, Methodical

- Independent Learning and Classes as a Unit

- Methods for Structuring

- 4.3 Beyond the classroom - explore, connect, grow professionally

- 5 Motivation & Resilience - Staying Well While Studying

- 5.1 Staying motivated - set goals, overcome procrastination

- 5.2 Managing pressure - understand stress and take action

- 5.3 Keeping your balance - rest, move, connect

- 5.4 When life gets tough - use support

- 6 Learning Techniques & Self-Management - Making Learning Effective

- 6.1 Understanding Learning - A Process, Not a Type

- 6.2 Notes & Annotations - Making Thinking Visible

- 6.3 Reading Strategies - From Initial Overview to Deep Understanding

- 6.4 Using AI in Your Studies - Purposeful, Responsible and Learning-Oriented

1 Getting Started - Understanding Your Learning Environment ^ top

Starting a university programme - whether at Bachelor’s or Master’s level - is a major change. It means moving from school, work, or other life experiences into a new learning environment with its own expectations, opportunities, and ways of working. Some students start right after school or a previous degree, while others bring valuable work or personal experience. No matter your background, university is a place for academic learning, personal growth, and active participation in society.

Learning at a university is clearly different from school-based formats. It is characterised by personal responsibility, critical engagement, application-oriented knowledge transfer, and a multiperspective learning culture. Multiperspectivity in this context means that topics, questions, or problems are not considered from only one point of view. Instead, different academic disciplines, methodological approaches, professional experiences, and personal backgrounds are included. This creates a broader and more critical understanding, makes connections visible, and encourages creative solutions. Study content is not an end in itself but part of a larger context that addresses social, technological, and ecological issues and contributes to the development of sustainable solutions. University is also a social space where people with different experiences, backgrounds, and perspectives come together. To learn successfully in such a setting, certain attitudes are important: respect, openness, reliability, the ability to give and receive constructive feedback, and communication that is fair and inclusive. These are the foundations for working well with others.

This chapter describes the key principles of studying at our university in the degree programmes Energy & Sustainability Management and Facility & Real Estate Management. It explains structural and cultural differences compared to school, reflects on the relationship between teaching and self-responsibility, and highlights the main conditions for good cooperation. The focus lies on the question of the framework under which learning can be successful-promoting performance, ensuring social fairness, and strengthening awareness of one’s own effectiveness. Successful learning at a university is not only a matter of content or methods; it is largely based on trusting, respectful, and dialogical relationships between lecturers and students. Good teaching-learning relationships provide orientation, enable feedback, support individual development, and strengthen self-efficacy. They form the framework for collaborative academic work on equal footing, shaped by mutual appreciation, active participation, and shared responsibility for the learning process.

1.1 University is not school - how studying really works ^ top

In the first weeks of a degree programme, university is often compared to school. Words like "class group", "lessons", "timetable" or "break" still come up frequently. This is understandable - after many years in school, such ways of thinking and speaking feel familiar. Many things may seem the same: fixed times, group work, and set topics.

However, this impression is misleading. A university is not just a continuation of school. It is a place with its own identity, different goals, and different expectations for students and staff. In school, learning often focuses on memorising facts, passing tests, and covering the curriculum. At university, learning is about taking responsibility for your own study, dealing with complex topics, and thinking critically. It includes doing research, working on projects, and reflecting on what and how you learn and it means developing a scientific way of thinking.

In contrast to school, learning at university does not take place on the basis of detailed instruction or close supervision by lecturers, but through active, self-organised, and continuously reflected personal action. This change concerns not only the form of knowledge transfer but also a different attitude towards learning and a new role that students take on.

Actively shape your learning culture

let go of the idea that everything at university is planned out for you.

set your own goals instead of only focusing on grades or assessments.

see university not as a service you consume, but as a space you help shape.

take time to reflect: what expectations do you bring? What are you ready to contribute?

Checklist: Preparations for Starting Your Studies ^ top

Before starting a degree, there are no compulsory reading lists, no prescribed learning materials, and no specific subject-related prerequisites. The entry into university studies is designed in such a way that it can begin from a wide range of starting points and subject areas. Students bring along very different prior knowledge, competences, and either professional or school-related experiences. This diversity is intentional and is taken into account within the study programme. In some cases, prior knowledge can be formally recognised, allowing individual study paths to be shaped accordingly.

English language competence is essential for participation in this programme, as most courses, academic materials, and a large part of the literature are provided in English. However, it is important to emphasise that this does not mean that every student or lecturer communicates with perfect grammar or in a native-like way. The programme brings together people from many different countries, cultures, and professional backgrounds. As a result, there are a variety of English levels, speaking styles, and accents present in lectures, seminars, and group work. Even some lecturers may not be highly fluent in English, and their accents or vocabulary may differ. This diversity should not be seen as a barrier, but as a resource that reflects the international character of the programme.

What really counts in the academic context is not linguistic perfection but the ability to communicate effectively:

- to understand the main ideas of texts, lectures, and discussions

- to express your own thoughts and arguments in a clear way

- to participate actively in teamwork

- to contribute to debates and group projects with confidence

It is normal to make mistakes, search for words, or sometimes struggle with complex academic texts. What matters is openness, the willingness to practise, and the courage to speak up. Developing self-confidence to communicate in English, even if your sentences are not always perfect, is a key skill for study success.

Support is available through peers, who often share similar challenges, as well as through digital tools such as dictionaries, writing aids, or grammar checkers. Study groups and tandem partnerships can also be valuable spaces for practising English in a supportive environment. Making use of feedback helps to improve gradually.

For international students, it is also highly recommended to acquire basic German skills to manage daily life. Even simple competences in German - ordering food, reading signs, or greeting neighbours - make everyday routines easier and strengthen the feeling of belonging. The university offers German language courses during the programme, and there are many informal opportunities to practise, for example by watching local media, joining social activities, or speaking with peers.

Taken together, the study environment encourages openness, mutual support, and continuous learning. Success is not about flawless language, but about curiosity, participation, and the readiness to communicate across differences.

At the same time, this also means that during the course of study it may become clear that certain foundations or competences are missing or need further development. Self-directed learning plays a central role at university, and working together with fellow students offers many opportunities for exchange, mutual support, and balancing different strengths. In this way, missing knowledge can be gradually supplemented, deepened, and integrated into the overall context.

What is decisive from the outset, however, is operational readiness: students who, at the beginning of the semester, have reliable technical equipment, are confident in using key software applications, and have organised their working environment, can concentrate fully on content and learning processes. This includes having a powerful laptop or tablet, the ability to use standard software in a stable and efficient way, and a structured working environment that supports both focused study and participation in online formats. A carefully prepared organisational framework makes the start considerably easier and subject-related gaps can then be addressed in a targeted way without unnecessary distraction.

1.2 Studying Combines Research & Reflection - More Than Professional & Training or Vocational Education ^ top

Studying at a university differs fundamentally from professional training or continuing education. While short courses or training programmes mainly focus on current specialist knowledge and specific skills for immediate use in the workplace, a degree programme pursues a broader aim with the integration of knowledge acquisition, academic research and personal development.

At the centre is academic work and research: asking questions, investigating problems systematically, and reflecting critically on results. This forms the foundation for managing new and unexpected challenges in professional life.

At the same time, a degree programme promotes personal development. Analytical and communication skills, taking responsibility in projects or teams, as well as the ability to represent one’s own position independently, are deliberately strengthened. These overarching competences are often referred to as key competences and are not limited to a single professional field, but open up diverse career paths and social roles.

Another important feature is independent learning. Unlike in school or professional training, responsibility for successful learning rests primarily with the students themselves. Strategies for engaging with complex material and a continuous involvement with content are decisive. In this way, the capacity for lifelong learning is trained - a central objective within the European Higher Education Area.

In addition, students develop the competence to work with complex texts and regulations. The focus is not on memorising individual paragraphs, but on understanding structures, recognising connections, and responding flexibly to changes. Laws and standards are constantly evolving. Therefore, what is important and in demand is the ability to examine these developments critically and to place them within one’s own professional context.

A special format in university studies are seminars, which are characterised by intensive discussions, independent research, and written work. There are also integrated courses (ILVs) that combine theoretical knowledge transfer with practical exercises in a single unit. Assessment may be continuous, meaning that evaluation takes place throughout the semester based on active participation, assignments, presentations, or tests. Unlike lectures, which are mainly focused on providing basic knowledge, seminars and ILVs require active involvement. Here, content is worked on collectively by students and discussed in groups together with the lecturers. Preparatory readings, presentations, group work, or short inputs may be given, which are then explored in open discussion. These formats require social and communication skills. Different perspectives come together, ideas are negotiated, debated, and solutions are sought collectively. Seminars and ILVs are therefore not only places of knowledge transfer, but also training grounds for cooperation, reflection, and independent thinking. They directly prepare students for professional situations in which discussion, teamwork, and presentation are essential.

Studying is More Than Continuing Education

Not everything is predetermined: set out on your own path to discover knowledge and create new ideas.

The material presented is only a starting point: your initiative and your questions deepen the learning process.

Professional practice alone is not enough: studying teaches you to reflect critically and to carry out independent research.

Learning does not end with an exam: use your studies to practise ongoing development and openness to new challenges.

1.3 What Studying Means - Freedom, Responsibility, Personal Growth ^ top

The university is not only a place for subject-specific knowledge transfer, but also a space for social and personal development. It sees itself as a platform where new perspectives can be explored, current challenges reflected upon, and sustainable solutions developed. In this sense, the university becomes a social learning environment that invites participation and co-creation.

This idea of the university as a platform is especially important in degree programmes that deal with complex areas of change such as sustainability, real estate, or facility management. In these fields, students are not only learners. They also take on roles as co-researchers, co-creators, and people who share responsibility. The university offers spaces to explore important social questions, to define your own research interests, and to actively take part in shaping the future.

This platform concept is particularly relevant in degree programmes that deal with complex fields of transformation, such as sustainability studies, real estate economics, or facility management. In these contexts, students are not only learners but also co-researchers, co-creators, and co-responsible actors. The university provides spaces to engage with societal issues, to develop individual research questions, and to actively participate in shaping the future. Key elements of this platform approach are exchange, diversity of perspectives, and a culture of discourse. A culture of discourse means a respectful and open way of communicating, in which different viewpoints are heard, critically reflected upon, and constructively developed further. The goal is not to find supposedly "correct" answers, but to develop well-founded positions. This takes place through dialogue, critical engagement, and collective thinking.

Make active use of your learning environment

take part in projects, seminars and discussion forums to explore your ideas.

look for links between academic topics and real-world problems.

keep track of your learning progress, open questions, and new insights.

see university as a space for meaningful exchange - not just a place for tests.

1.4 Learning is Relational - Teachers as Learning Companions ^ top

An the university context, not only the role of students changes, but also that of lecturers. While in school the position of authority often dominates, lecturers at university primarily act as initiators, coaches, and discussion partners. They see themselves as supporters in the learning process rather than as controlling authorities. This changed attitude makes collaboration on equal terms possible. However, it requires that students are willing to take responsibility for their own learning path. This includes active participation in courses, seeking feedback, and asking questions. In addition, the ability to deal constructively with uncertainty is essential-not seeing it as a disturbance, but as a starting point for deeper reflection, new perspectives, and individual learning.

The university context thrives on dialogue. Lecturers contribute expertise, didactic experience, and structural guidance. Students bring curiosity, their own questions, and relevant practical experience. Learning emerges where both perspectives productively come together. Academic success is not only a matter of self-discipline or subject knowledge. Relationships between lecturers and students play a central role. A trusting, appreciative, and dialogue-oriented relationship significantly increases students’ motivation, self-efficacy, and engagement. Teaching-learning relationships on equal footing foster a sense of belonging, create space for reflective thinking, and allow for individual feedback. They encourage openness to express uncertainties, to ask questions, and to participate actively. In a study environment shaped by diversity, complexity, and dynamic change, such relationships are more than just "soft skills" and they become essential qualities for successful learning.

Foster respectful relationships - on equal terms

talk to your lecturers - not just during assessments, but also informally.

use feedback not just to improve grades, but to grow and develop.

prepare for each session with your own questions and ideas.

accept uncertainty as part of the learning process - it is not a sign of failure.

1.5 Encouragement & Challenge - What is Expected ^ top

Learning at university depends on a balance between support and challenge. Support means getting help, useful resources, encouraging feedback, and guidance from others. Challenge means being stretched to think deeply, leave your comfort zone, and take responsibility for your own ideas and actions.

Challenging and supporting at the same time is not a contradiction, but a necessary condition for a successful period of study. Learning does not happen through comfort, but through irritation, effort, and engagement. Lecturers provide guidance, but they do not take over responsibility. This lies with the students themselves. A study routine that supports this is characterised by open questions, challenges in time management, complex task formats, and diverse communication situations. Those who show themselves to be capable of learning, reflective, and willing to cooperate will benefit not only during their studies but also in their future professional lives.

Own your learning process

set clear, realistic goals at the start of each semester - for subject knowledge, methods, and personal growth.

keep track of your progress - for example, by writing a learning journal.

see difficulties and setbacks as part of the learning journey - reflect on what went wrong and make changes.

take responsibility for your development - even when there are no clear external rules or deadlines.

1.6 Learning Together - Why Diversity is a Strength ^ top

Universities are diverse spaces where people of different age groups, cultural backgrounds, professional experiences, identities, and life realities come together. This heterogeneity is not a disruptive factor but an essential resource for collaborative learning, multiple perspectives, and innovation. Diversity makes it possible to view complex challenges from different angles and to develop new solutions together.

An inclusive, discrimination-aware, and discrimination-reduced learning culture - a "safer space" - forms the foundation for a vibrant, fair, and productive study environment. Universities are spaces that offer all participants - regardless of gender, social background, sexual orientation, disability, religion, nationality, language, mental health, or other personal circumstances - equal access to education, recognition, and participation. Respectful cooperation is based on democratic values, mutual appreciation, and an open and reflective dialogue climate. The goal is not harmony in the sense of avoiding conflict, but rather dealing with differences in a way that is shaped by respect, listening, willingness to take on other perspectives, and the ability to tolerate ambiguity (= diversity of meaning, uncertainty).

Awareness as Attitude and Practice ^ top

Awareness means conscious attention to exclusions, boundary violations, and structural discrimination in everyday study life. It starts with individual attitude and means:

-

Use language consciously: Diversity-sensitive formulations, respectful forms of address, avoidance of stereotypes, and the recognition of individual self-designations are expressions of respect and responsibility.

-

Naming discrimination when it happens: Even small things - like rude questions or excluding someone without meaning to - should be addressed calmly and supportively.

-

Showing empathy and acting with care: Don’t look away when others are being treated unfairly. Help create spaces where everyone feels seen and safe.

-

Willingness to learn and reflect: No one is without bias. What matters is the willingness to listen, learn from discomfort, and rethink your own actions.

These principles are not "additional topics" but essential key competences. They influence not only how people live and work together during their studies, but also the professional handling of diversity in later fields such as sustainability management, real estate, or working with different stakeholder groups in facility management. University studies can be a central place where these principles are experienced in practice. Where lecturers and students meet as equal partners in the educational process, a social climate emerges that enables security, development, and engagement at the same time.

Value diversity - embody awareness

meet your fellow students with openness - especially when you have different opinions or experiences.

speak in ways that include everyone - and respect how people choose to describe themselves.

listen before judging - and ask questions instead of making assumptions.

respond carefully when someone says something hurtful - whether it’s from others or yourself.

help create a learning space where everyone feels safe, respected, and seen.

1.7 Digital Support - Recognising Opportunities, Taking Responsibility ^ top

Studying takes place in an environment where digital assistance systems are available at all times. As a result, information usually no longer has to be gathered laboriously, but often appears instantly and seemingly complete. This convenience can be a relief, but it also carries a risk. Relying solely on ready-made results means missing the opportunity to train one’s own thinking and to develop as an independent personality during one’s studies.

-

Studying is more than the pursuit of examinations.

It is a period in which essential competences are tested, consolidated, and further developed. This includes the ability not merely to consume information, but to classify it, examine contradictions, and assess whether it is truly relevant to one’s own research questions. Digital systems provide answers, but they cannot decide which of these answers are meaningful, which implicit assumptions underlie them, or how they should be placed within a broader context. This responsibility remains with the students themselves. -

The period of study is also a phase of personal growth.

University offers time to further develop one’s judgement, self-reflection, ability to engage in discourse, creativity, and ethical reasoning. These skills are also crucial for later professional success. Our fields of work are increasingly shaped by uncertainty, time pressure, cultural diversity, and conflicting interests. This requires personalities who are able to assess complex situations, justify decisions, and take responsibility for their actions. Those who practise this during their studies gain a competence base that extends far beyond graduation. -

Judgement plays a key role.

This means reviewing information critically, setting priorities, and making decisions that remain valid even under uncertainty. Especially in times of digital assistance systems, it becomes clear that not every answer has the same value. It is often necessary to distinguish between superficial generalisations and well-founded analyses. Self-reflection complements this ability by making it possible to question one’s own approach and to learn from mistakes. Those who reflect regularly not only recognise progress but also identify blind spots and thus develop greater flexibility in dealing with challenges. -

Creativity takes on special importance in this process.

Digital systems are strong at reproducing patterns and suggesting familiar solutions, since they are trained on existing data and derive statistical probabilities from them. They therefore mainly rely on what is already available and only rarely open up genuinely new ways of thinking or acting. Something truly new arises only when these patterns are broken, rethought, and transferred into new contexts. Creativity means combining what seems unrelated, asking unconventional questions, and not settling for obvious answers. This ability is valuable not only in university studies but also in professional contexts, where innovation and problem-solving skills are becoming increasingly essential. -

Discourse skills are, finally, an indispensable element.

While digital systems can generate suggestions, the lively exchange between people remains irreplaceable. Discussions make contradictions visible, open up new perspectives, and challenge us to sharpen arguments. Discourse goes beyond discussion: it does not only mean speaking and counter-speaking, but a deeper, structured process of collective reflection in which knowledge, experiences, and perspectives are connected. The ability to deal productively with different positions, to tolerate ambiguity, and to arrive at solutions together shapes the quality of both academic and professional work.

Digital support can be a valuable catalyst in all fields. However, this requires that it is used consciously. It opens access to complex topics, provides inspiration for new ways of thinking, and makes it easier to approach difficult questions. Yet it is only through critical examination, methodological evaluation, creative further development, and discussion with others that these impulses are transformed into genuine learning and personal development. The benefit of advanced systems does not lie in quick access to answers, but in the opportunity to shape one’s own maturation process, to train judgement, to practise self-reflection, to unfold creativity, and to expand discourse skills. From this perspective, studying means understanding digital assistance systems not as a substitute, but as a resonance space of one’s own thinking. A resonance space emerges when diversity is welcomed, different voices are heard, and contradictions are not blocked but used as a starting point for deeper engagement. It is fostered by open questions, active listening, the courage to share one’s own uncertainties, and the willingness to seriously include others’ arguments in one’s reflection. Digital assistance systems can play an important role by mirroring patterns in data, suggesting alternative formulations or perspectives, or encouraging students through their responses to critically examine their own thoughts. Their strength does not lie in delivering ready-made solutions, but in offering impulses that can be taken up, questioned, and developed further in exchange with others. A bubble, on the other hand, narrows when only confirming feedback is sought, differing perspectives are ignored, or critical questions are rejected. In this way, communication remains trapped in the circle of the familiar, without enabling new thinking. Real progress arises where these impulses are not adopted uncritically but are discussed critically, recombined, and creatively shaped. Thus, the period of study becomes an experimental space in which digital support and human effort meet - with the goal of developing competences that are crucial both in academic studies and in professional life.

Integrate Technology - Develop Personality

use digital assistance systems as a starting point to develop your own ideas instead of simply adopting answers.

evaluate each output critically: question plausibility, identify possible distortions, and assess the line of reasoning.

train your judgement by weighing digital suggestions against alternative perspectives and justifying your decisions.

practise self-reflection by recording how you have used assistance systems and what insights of your own have resulted.

foster creativity by breaking, transforming, and transferring digital patterns into new contexts.

seek discussions with others in order to analyse, question, and further develop digital results collectively.

view your studies as a laboratory: a reflective and creative approach to assistance systems strengthens those skills that are indispensable both in higher education and in professional life.

1.8 Presence & Exchange - Creating Resonance Spaces, Building Connections ^ top

Studying does not only mean working through content and passing exams. What is also decisive is the quality of the encounters that arise during the course of study. Courses, discussions, and collaborative work create resonance spaces that are difficult to replace when working alone. It is precisely where ideas collide, questions are asked, and different perspectives become visible that deeper understanding and new viewpoints emerge. Where there is no compulsory attendance, freedom opens up - but this also means great responsibility. Without compulsory attendance, it takes a conscious decision about when and how to use opportunities for personal exchange. Attendance is not an end in itself or a mere formality. Its value lies in the conversations, in spontaneous questioning, in direct feedback, and in the experience of being part of a community. Such experiences help not only to expand knowledge but also to strengthen belonging and motivation.

-

Direct exchange acts as a catalyst for personal development. Arguments become clearer when they must be expressed in front of others. Uncertainties are easier to resolve in dialogue than in solitary study. Often, it is precisely the unexpected contributions of fellow students that lead to insights reaching far beyond what prepared texts or digital systems can provide.

-

Presence unfolds its potential not only in lectures and seminars. The times before and after classes also provide valuable opportunities for encounters: conversations in the cafeteria, brief exchanges in the corridor, spontaneous discussions after a seminar. These informal moments create closeness, trust, and a sense of belonging. They also make it possible to meet lecturers as approachable individuals beyond formal frameworks and to get to know fellow students better.

-

The university offers spaces specifically designed for collaborative learning and creative work. Laboratories, project workshops, or open creative areas invite students to test ideas in practice, experiment together, and develop solutions. Such spaces make learning tangible and provide a foundation for linking theory with practice. They extend study opportunities far beyond listening - towards independent and cooperative shaping.

Presence in higher education therefore means more than mere physical attendance. It is a field for learning discursive ability, teamwork, and social competence - skills that are of central importance in any professional context. In complex work environments, it is not only subject expertise that counts, but also the ability to persuade in dialogue, to develop solutions together, and to build sustainable relationships. University study offers the opportunity to practise and refine exactly these qualities - in seminars, during breaks, in laboratories, and in all the spaces that higher education provides as a shared environment of experience.

Learning Together - Building Networks

Make use of encounters before and after classes - conversations in the cafeteria, on campus, or in the corridor build trust and create new impulses.

Seek direct exchange with fellow students to initiate spontaneous discussions and sharpen arguments through dialogue.

Approach lecturers outside of classes to take up new ideas and clarify open questions.

Actively explore laboratories, workshops, and creative areas - collaborative experimentation makes learning tangible and opens up new perspectives.

Understand times of presence as resonance spaces: they strengthen belonging, foster motivation, and enhance your teamwork and discursive skills.

2 Five Features of Your Study Programme ^ top

Studying here means working scientifically, taking responsibility, and applying knowledge in practice. A mix of personal guidance, feedback, independent study, and project work shapes everyday learning.

-

Study = Science

Great emphasis is placed on academic work and research. Reading specialist texts is part of daily study, and students practise formulating ideas clearly and supporting every statement with evidence. Correct referencing is considered essential. -

Ask Questions

Contact with lecturers is straightforward. Questions are best asked in personal conversations, in an atmosphere that allows for follow-up and open feedback. In this way, problems can be identified early and solutions found more easily. Dialogue itself becomes part of learning, as questions and responses deepen understanding and open new perspectives. -

Get Feedback Before It Counts

It is possible to receive comments while tasks are still in progress. Mistakes become visible at an early stage, and improvements can be made straight away. Learning becomes an ongoing process in which results are refined step by step, leading to a deeper and more sustainable development of skills. -

Work Independently & Take Responsibility

Studying requires self-organisation. Content is worked on independently, and self-study makes up the largest part of study time. Often not all structures or complete data are provided, so part of learning is dealing with incomplete information and working into new challenges. This is a competence that is equally important in professional life. -

Learning by Doing

Exercises, project work, and practical applications are an integral part of the degree programme. They complement the academic standards and show how knowledge can be applied in real situations. Hands-on use of open-source tools, own coding, and practical experience deepen competences and train the ability to design solutions that are not only theoretical but also feasible and problem-oriented. This creates a clear advantage for professional practice.

3 Netiquette in Academic Settings - Taking Shared Responsibility ^ top

A respectful, reliable, and professional approach to communication and collaboration is essential for effective learning whether on campus, online, or via written messages. Universities bring together people from diverse backgrounds, with different experiences, cultures, and perspectives. This diversity is enriching, but it only becomes a strength when everyone actively contributes to a considerate and constructive environment. Netiquette means more than politeness. It reflects a shared mindset shaped by clarity, respect, participation, and care for one another. It is not about perfect manners, but about the willingness to take responsibility for one’s own behaviour whether in everyday situations such as an email, during a lecture, or in a conflict discussion.

Eight key principles support a healthy and inclusive academic culture:

-

Respect - treating others with appreciation and avoiding harmful language or actions

-

Active participation - engaging with content, discussions, and group work

-

Privacy - protecting personal data and confidential information

-

Reliability - keeping commitments and being accountable

-

Empathy - understanding and valuing different perspectives and life situations

-

Constructiveness - communicating in a thoughtful, reflective, and helpful manner

-

Punctuality - managing time responsibly and being prepared

-

Community spirit - shaping a positive and supportive learning environment together

These principles are expressed in everyday actions - in tone, body language, communication style, and how criticism or feedback is handled. Netiquette is not about rigid rules; it is a living practice that grows with every choice to take others seriously and to see oneself as part of a shared responsibility for learning.

You are part of this culture. Thank you for helping to shape it.

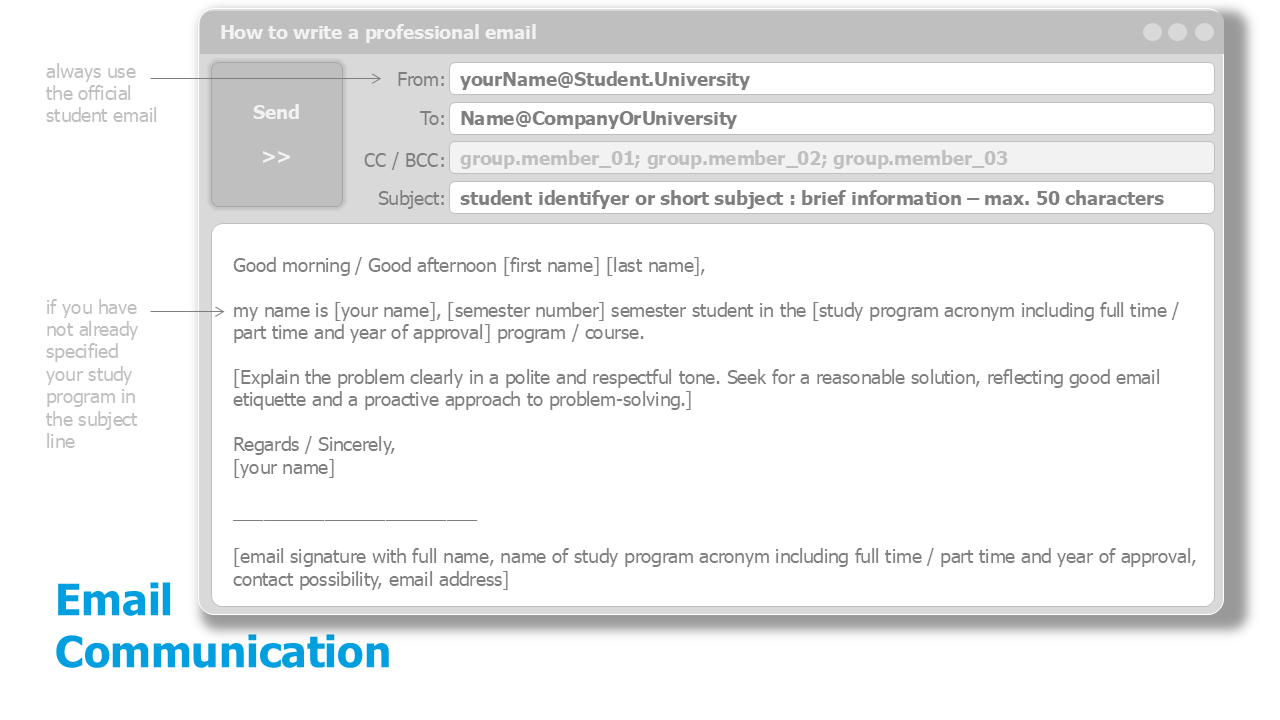

3.1 Writing effective emails - clear, polite and to the point ^ top

Emails are often your first point of contact - they influence the tone of any cooperation.

-

Start with a clear subject line - include your programme code (e.g. FIM.vzB.22) to help classify your request.

-

Use a respectful greeting - "Dear Programme Management Team" is always appropriate if unsure.

-

Be concise, constructive and professional - avoid emotional or demanding language.

-

End with a complete written closing - please avoid shortcuts like "BR" or "Thx".

-

Include a full signature with your name, programme, intake/year and student ID - this speeds up processing and shows respect.

3.2 Showing up online - seen, heard and prepared ^ top

A learning atmosphere also develops in virtual spaces - through presence and attention.

-

Check your technology and login early - to avoid delays and stay focused.

-

Use headphones or a headset - to avoid background noise and audio disruptions.

-

Turn on your camera - being visible supports engagement and builds connection.

-

Keep your microphone muted - unless you are speaking.

-

Do not record the session - recordings without permission violate privacy and legal rules.

3.3 Being present in class - punctual, focused, involved ^ top

The lecture room is a shared learning space - attention and respect make a difference.

-

Be on time - arriving late disrupts the learning environment.

-

Talk to peers only during group activities - side conversations are distracting.

-

Use laptops and phones for learning only - unrelated use distracts everyone.

-

Do not eat or drink in the lecture hall - it’s a place for concentration.

-

Leave your space tidy - take all your belongings and waste with you.

3.4 Submitting requests - complete, structured, on time ^ top

A clear and well-prepared request helps everyone involved - including you.

-

Check FAQs, guides and forums first - many questions are already answered.

-

Contact the Study Management first for requests - only use the programme head as last resort.

-

Submit documents digitally and in full - ideally as a PDF with clear attachments.

-

If you are caring for a sick child or dependent person - you can still submit a sick note.

3.5 Succeeding in exams - fair effort, smart strategies ^ top

Exams show what you’ve learned - not how well you can bend the rules.

-

Do not share or publish exam questions - this is a legal violation.

-

Marks are final and not negotiable - feedback is welcome, appeals are not.

-

Use your three exam attempts - only the passed attempt appears on your transcript. No need to stress.

3.6 Dealing with conflict - stay calm, stay kind, seek solutions ^ top

Stress, disagreement or misunderstandings can happen - how we deal with them matters.

-

Do not post hurtful or personal content - even private chat groups are not exempt from legal and ethical standards.

-

Bullying or discrimination has no place - the university is a safe and inclusive space.

-

Give and receive feedback respectfully - constructive criticism helps us grow.

-

**No gossiping about lecturers, content or teaching methods."" Constructive criticism and suggestions for improvement are important - but it should be expressed directly, honestly and on equal footing. Speak to your lecturers instead of venting in group chats or behind their backs. Real change only happens through open dialogue.

4 Planning & Managing Your Studies - Organise Time, Shape Success ^ top

Study success also means a realistic assessment and organisation of one’s study time and the related "energy" investment. Whether full-time or part-time, a degree programme always requires conscious engagement with the overall workload, individual learning organisation, and the wide range of requirements and opportunities both within and outside the university. Independent learning, project work, exam preparation, engagement with additional academic literature, and participation in extracurricular activities are all expected in the course of study.

This chapter explains how to understand, plan, and use your study time in a helpful way. It has four parts: the total workload of a semester, tips for learning on your own, how to prepare and follow up on lectures and assignments, and how to make use of extra learning offers inside and outside the university.

4.1 Planning Study Time - Realistic, Self-Directed, Reflective ^ top

The time available is limited. This means that structuring it is essential for academic success. A semester comprises a workload of 30 ECTS credits. ECTS stands for the European Credit Transfer System and enables comparison of the intensity of academic learning across Europe. At Austrian universities of applied sciences, one ECTS equals an average workload of 25 hours. Of this, about 5.5 hours per week are typically allocated to planned attendance in classes - the much larger share must be organised as self-study. This includes working on projects, group assignments, essays and seminar papers, as well as individual preparation and revision. Altogether, the workload amounts to roughly 750 hours per semester, corresponding to around 38 to 41 hours per week. At the University of Applied Sciences Kufstein Tirol, this calculation applies regardless of whether the programme is full-time or part-time.

Study time is therefore not the same as timetable hours. It is an individual working framework that must be actively shaped by planning, prioritising, making conscious learning decisions, and scheduling time for recovery.

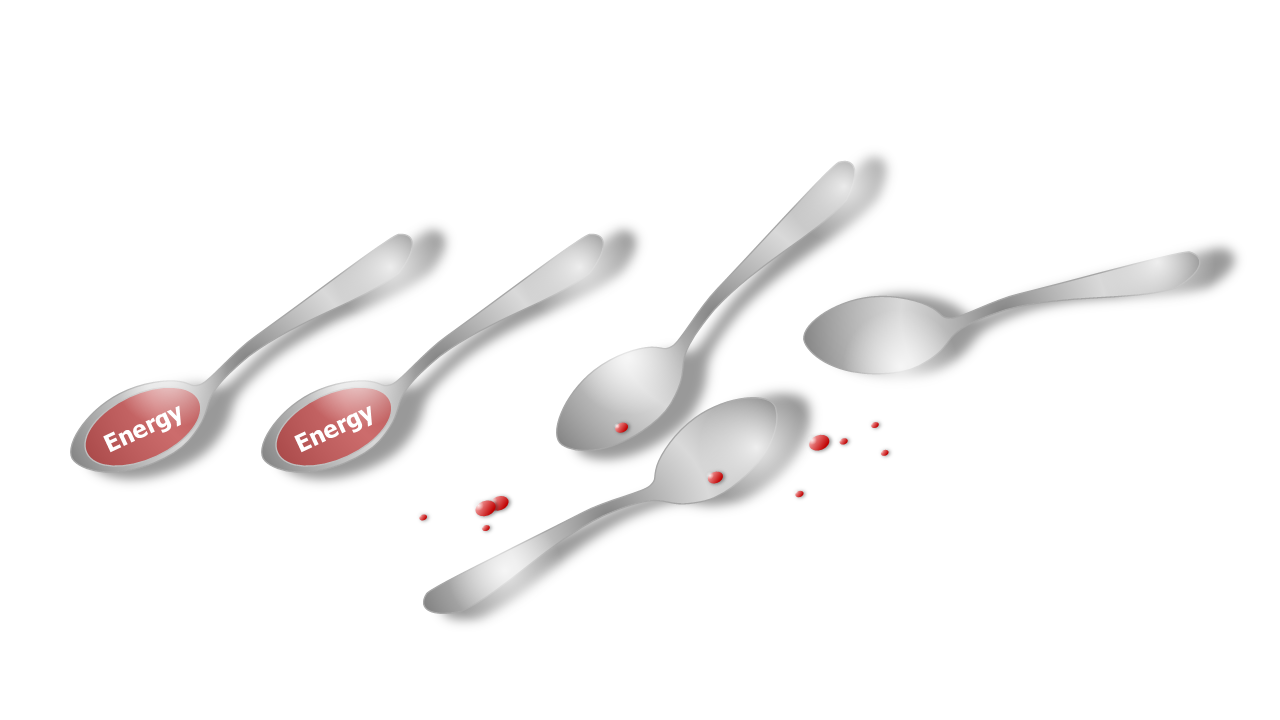

Energy instead of Time Management ^ top

Looking only at the time needed for a task is too limited. Even if the calendar seems to offer many free hours, the energy to use them effectively may be missing. What matters is not only the time available, but also personal energy. A helpful model is the Spoon Theory by Christine Miserandino. It describes that each person has only a limited number of "spoons" per day - symbolising the energy available for activities. Every action - whether attending a lecture, writing a paper, working, doing sports, or talking to friends - consumes spoons or may even generate energy. Once energy is used up, no further activity can be managed without overload.

Productivity cannot be increased without limit. Energy and time are finite resources. Effectiveness arises not from squeezing more tasks into the calendar but from using available time and energy deliberately.

Prioritising Energy and Time ^ top

Prioritisation is key. Those who try to fit as many tasks as possible into a single day risk consuming too many spoons - too much energy - at once. It is more effective to identify one to three particularly important and energy-intensive tasks and give them priority. Other tasks can be managed later or shifted to days with more available spoons.

- Match tasks to energy levels: demanding activities should be scheduled for high-energy phases, routines for times of lower capacity.

- Take recovery seriously: breaks, exercise, sleep, and social contacts are not "lost time" but necessary to restore spoons.

- Practise self-awareness: recognising when limits are reached protects long-term health and performance.

From this perspective, time is a fixed factor, whereas energy is variable and individual. Those who manage only time treat hours as empty boxes to be filled at will. Those who value time recognise that not every hour is equally productive - and that it is wise not to overload days. Academic success results not simply from more working hours, but from a reflective use of energy.

Example

| Task | Time required | Energy spent | Energy gained / Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attend class | 2 h | 2 spoons | 0 spoons |

| Read chapter in textbook | 1 h | 3 spoons | 0 spoons |

| Write section of essay | 3 h | 5 spoons | 0 spoons |

| Exercise session | 1 h | 2 spoons | +3 spoons |

| Meeting with friends | 2 h | 2 spoons | +2 spoons |

| Walk / break | 0.5 h | 1 spoon | +2 spoons |

| Adequate sleep | 8 h | 0 spoons | +8 spoons |

| Total | 17.5 h | -15 spoons | +15 spoons |

Plan study time with energy in mind

- Structure your days by both time and energy: schedule demanding tasks for high-energy phases, routine activities for low-energy phases.

- Set priorities by selecting three key tasks that require many spoons and give them precedence.

- Create a semester plan that combines deadlines and exams with sufficient breaks, recovery periods, and opportunities for gaining energy.

- Take recovery seriously - walks, exercise, social contacts, or quiet phases are not "lost time" but conditions for regaining spoons.

- Consider invisible tasks such as research, working with literature, formatting, or integrating feedback into your learning - they often require more energy and time than expected.

- Reflect regularly: which activities consume more spoons than anticipated? How can planning be adapted to maintain balance between energy expenditure, recovery, and the limited time in a day?

4.2 Shaping Independent Learning - Active, Goal-Oriented, Methodical ^ top

Most study time at university does not consist of attending classes, but of self-directed learning. For every teaching unit of typically 45 minutes, an average of 60 to 150 minutes of independent learning is expected to acquire the required competences. This is 1.2 to 3.45 times more time than spent in class. Independent learning is not a passive act of receiving or merely consuming additional information or repeating lecture notes; rather, it is an active, structured, and methodologically guided process. It requires self-discipline, clear goals, prioritisation, and realistic planning - particularly when multiple demands need to be managed simultaneously.

Independent Learning and Classes as a Unit ^ top

Learning forms a continuous process of preparation, participation, and follow-up. These three phases interlock like a cycle: prior knowledge is activated, new content is actively processed, and results are consolidated, applied, and adjusted with feedback. This recurring process deepens understanding, strengthens retention and transfer, and reduces the workload of revision during exam periods.

-

Preparation includes reviewing provided materials, reading recommended literature, formulating questions or hypotheses, and activating prior knowledge. The aim is to enter the session with a basic orientation and to be able to connect more effectively.

-

Teaching session involves active participation during class. This includes structured note-taking, asking questions, contributing to discussions, identifying connections, and marking open issues. It is important not to receive content passively, but to engage actively, linking it to personal experience or other study content.

-

Follow-up means organising and expanding notes, systematising core content, clarifying open questions, and connecting material to other topics. Structured follow-up supports long-term knowledge retention, the development of one’s own arguments, and exam preparation.

In addition, students must independently complete academic assignments: seminar papers, project reports, presentations, and talks. These formats combine subject knowledge with methodological, writing, and communication requirements.

Methods for Structuring ^ top

Various methods are available to support this process, which can be combined depending on individual working styles. Here is an example list of different methods. These well-known approaches have been adapted to the time-energy connection.

-

Prioritisation: Energy-Eisenhower Matrix:

This method extends the well-known Eisenhower Matrix for prioritising tasks by adding the aspect of required energy. Tasks are categorised according to importance, urgency, and energy demand (spoons). This creates an overview of which tasks should be completed, delegated, or avoided at which times.High Importance Low Importance High Energy Demand A - Core Tasks (urgent & important)

Very relevant, high energy cost, deadline-bound.

→ Complete during high-energy phases.

Example: submitting a seminar paper, exam preparation.

B - Strategic Investments (important, not urgent)

Long-term relevance, high energy cost.

→ Schedule early, before they become urgent.

Example: literature research for a dissertation.C - Energy Wasters (neither important nor urgent)

Consume energy without benefit.

→ Eliminate.

Example: excessive formatting with no real relevance.Low Energy Demand D - Efficiency Tasks (important, not urgent)

Relevant, manageable energy cost.

→ Complete during low-energy phases or simplify/delegate.

Example: organising notes, checking reference lists.E - Minor Tasks (not important, but urgent)

Low relevance, low energy cost, external pressure.

→ Delegate or simplify.

Example: administrative details, compulsory forms.The matrix illustrates that not every task with time pressure is important, and not every important task can be handled in low-energy phases. Combining importance, urgency, and energy demand creates a tool that helps students use their limited spoons where they are most effective - and consistently avoid energy waste.

-

Weekly Structure: Energy-Time Blocking:

With this method, the week is divided into blocks. The decisive factor is not only available time, but also the energy profile across the week. A weekly plan reveals typical high and low phases: some days are more suitable for complex, energy-intensive tasks (e.g. Monday morning for essay writing), others for lighter activities (e.g. Friday evening for sorting literature or structuring notes).The key is not to plan every day equally intensively, but to steer energy purposefully. This shows on which days most spoons are available for core study tasks and on which days regeneration or smaller tasks are better scheduled. The result is a balanced weekly rhythm that prevents overload and ensures steady progress.

-

Structure for Small Study Units: Energy-Pomodoro Technique:

Here, a study task is divided into short units of a maximum of 25 minutes. Each unit corresponds to a specific energy demand ("spoons" as explained above). While simple tasks such as sorting notes may cost only one spoon, complex tasks such as analysing a study or drafting part of an essay require two or three spoons.Before each unit, a timer is set to concentrate effort and initiate breaks on time. Break length depends on the energy demand: after a light unit, five minutes may suffice, whereas after intensive sessions, ten to twenty minutes are more effective. Breaks should include restorative activities - standing up, moving, fresh air, drinking water, or short relaxation exercises.

If a task unexpectedly requires more energy than anticipated, it is advisable to end the unit early and take a longer break immediately. This prevents overload and keeps the energy balance stable. The decisive factor is not the number of units, but the balance: at the end of the day, energy expenditure should be offset by sufficient recovery.

Build a Functional Learning Routine

Record your progress in writing or digitally - for self-monitoring and motivation.

Read key texts before class - even if not everything is understood. Note down initial questions.

Revise notes directly after class. Highlight unclear points and add important terms.

Fix regular study times - in line with your energy levels, biorhythm, and commitments.

Prioritise tasks: use methods such as the Energy-Eisenhower Matrix to distinguish important & urgent, high-energy tasks from unimportant, non-urgent ones.

Break large tasks such as seminar papers into small steps - sequence them along a timeline and use methods such as Energy-Pomodoro or Energy-Time Blocking to structure study phases.

Plan buffer times for revisions, feedback, and technical issues - especially before deadlines or presentations.

Include literature beyond the required reading - to deepen understanding and provide context.

4.3 Beyond the classroom - explore, connect, grow professionally ^ top

Learning does not end at the edge of the timetable. The degree programmes in Energy & Sustainability Management and Facility & Real Estate Management are complemented by a variety of formats that promote interdisciplinary thinking, social responsibility, and cross-disciplinary dialogue. Many of these offerings are a compulsory part of the curriculum:

-

Guest Lectures: Evening discussions with guests from academia, industry, and politics. These are part of the curriculum’s focus on practice and research transfer.

-

Sustainable Days: A multi-day event series addressing socially relevant sustainability issues. Participation is a curricular requirement.

-

WinterSchool: An international project week focusing on sustainable urban and neighbourhood development. Real-life case studies are tackled in interdisciplinary teams.

In addition to these formats, students are encouraged to expand their learning by deepening their subject knowledge and engaging in academic activities beyond the university. Reading current specialist literature on industry-related developments - even outside of class - is a valuable way to build expertise and critical judgement. Relevant sources include:

- Trade journals and industry publications

- Academic journals and position papers

- White papers and reports from research institutes, public authorities, or companies

- Podcasts, newsletters, or blogs with a strong academic or professional focus

Professional conferences, public lectures, panel discussions, forums, and excursions also offer chances to explore current topics in real time, follow debates, and engage with experts.

Another key element is involvement in professional associations or subject-specific networks. Many of these organisations offer discounted student memberships and access to:

- Industry-specific knowledge, reports, and training

- Events and internal professional networks

- Mentoring schemes or job postings

- Opportunities to publish student work

Such engagement not only strengthens your professional network but also eases the transition into working life - for example, in sustainability consulting, real estate development, or facility services.

Consciously broaden your learning horizon

At the start of each semester, look for events inside and outside the university - such as lectures, excursions, or conferences.

Read current literature on key industry trends - not just the required readings.

Use newsletters, academic platforms, or library databases to discover new publications.

Join a professional association - many offer affordable student memberships and strong support.

Get involved: attend meetings, take part in discussions, and make purposeful connections.

Reflect: How does what you’ve read or experienced change your view of your studies and your future profession?

5 Motivation & Resilience - Staying Well While Studying ^ top

Between performance expectations, time pressure, self-doubt, and private responsibilities, students often face demanding situations that need to be managed. Especially in a practice-oriented university context, motivation, frustration tolerance, and resilience are key factors for academic success and mental well-being.

This chapter focuses on different aspects of managing both internal and external pressure: dealing with procrastination and performance stress, regulating tension, maintaining balance between academic and personal life, and making use of support systems - including legal and organisational options.

5.1 Staying motivated - set goals, overcome procrastination ^ top

Motivation is a dynamic factor that can change over the course of studies. It is influenced by clarity of goals, positive expectations, the belief in one’s ability to achieve results through personal effort (self-efficacy), as well as by social integration and a sense of meaning. At the same time, postponement (procrastination) is a widespread phenomenon in university life. Procrastination is often not caused by laziness, but by feelings of being overwhelmed, fear of failure, or lack of structure. In addition, tasks may deliberately contain open or missing details in order to encourage independent thinking, reflective decisions, and creative solutions. However, such uncertainties can also encourage procrastination if they are not actively addressed and if the challenge is not seen as an opportunity for personal growth. Dealing with such situations is made more difficult by unfavourable working environments, constant distractions, or unrealistic expectations.

Stay in action - even when motivation is low

Break large tasks into smaller, manageable steps.

Start with something low-threshold - for example, 10 minutes of focused work ("just get started").

Use methods like Pomodoro or time-blocking to ease into a productive rhythm.

Reflect on your goals regularly: Why are you studying? What motivates you in the long run?

5.2 Managing pressure - understand stress and take action ^ top

Performance pressure at university often arises from academic demands, expectations and sometimes from internal high pressure to succeed. Constant stress can lead to tension, poor concentration, irritability, withdrawal, or exhaustion. Active stress management is not a luxury - it is a key condition for sustainable learning and personal stability. Stress cannot be avoided entirely, but it can be managed with relaxation techniques, realistic planning, support from others, and mental strategies.

Take charge of your stress

Learn techniques such as progressive muscle relaxation, breathing exercises, or short mindfulness routines.

Pay attention to early signs of overload: sleep problems, difficulty focusing, or irritability.

Make use of counselling - most universities offer psychosocial services or learning support.

Talk to your lecturers when requirements feel unclear or excessive - communication often helps relieve pressure.

5.3 Keeping your balance - rest, move, connect ^ top

Studying is a demanding activity, even if it often feels less strictly regulated and more "relaxed." There is no time clock, no fixed working hours, and often no direct control. Precisely for this reason, it is easy to get the impression that studying is more flexible or less binding, even though the actual workload requires a high level of time commitment. To prevent studies, work, and private life from being in constant competition, clear boundaries, recovery, and social connections are needed. A healthy work-study-life balance not only promotes well-being but also increases the ability to learn. Key influencing factors are sleep, nutrition, exercise, and social contacts. Leisure, hobbies, and creative breaks also contribute to mental balance.

Keep your balance - for the long term

Schedule regular recovery time - sleep, movement, and offline time are part of your learning strategy.

Maintain social connections - also outside of university. Talking to others helps during difficult periods.

Take signs of exhaustion seriously - act early before they become chronic.

Develop personal routines that energise you: walks, music, sports, quiet moments, or conversations.

5.4 When life gets tough - use support ^ top

Not all burdens in university life can be "organised away." Especially towards the end of the semester, peaks in workload arise from multiple exams, submissions, and group projects. If, during this phase, additional and unforeseen serious personal or professional challenges and crises occur, situations may develop that feel overwhelming and can no longer be managed alone. In such cases, knowledge of legal frameworks and institutional support services can help. FH Kufstein Tirol offers various options to ease extraordinary individual stress situations:

-

Three attempts per exam: You may take up to three attempts per subject. Only the successful attempt appears on your transcript - failed attempts are not shown.

-

Study interruption: In justified cases, you may pause your studies for up to one year without losing previously earned credits.

-

Adapted exam formats: If you have a documented disability or chronic condition, you have the right to adapted assessment formats (e.g. extra time, digital submission, assistive tools).

-

Absence due to caregiving responsibilities: If you are responsible for children or dependent relatives and no alternative care is available, their illness can be a valid reason for absence.

Use your resources wisely

Start preparing for exams, presentations, and deadlines early - and build in buffer time.

Allow yourself study-free days during intense phases - recovery is part of the process.

Find out about support services offered by your university - e.g. counselling, learning coaching, or compensation for disadvantages.

Report high stress levels early - to your degree programme team, lecturers, or student advisory services.

6 Learning Techniques & Self-Management - Making Learning Effective ^ top

Taking notes helps to structure your thinking and make it visible. Reading strategies allow for a targeted approach to academic texts. A mindful use of digital tools and learning platforms opens up new ways to stay organised and deepen your understanding. Finally, personal routines, regular revision and constructive feedback play an important role in developing your learning over time.

Academic learning is an active, self-directed process - and therefore a personal one. What works best will depend on your goals, the context and your own habits. The aim of this chapter is to introduce core principles and offer practical approaches that can help you build and refine your learning practice.

6.1 Understanding Learning - A Process, Not a Type ^ top

In public debate, there is often talk of visual, auditory, or kinaesthetic learning types. This categorisation is not scientifically valid. Sustainable learning does not depend on a fixed "type", but on active engagement with content, contextualisation and repetition, as well as the personal relevance of what has been learned. Learning is particularly effective when information is not only received but also processed, questioned, and applied. Learning becomes effective when new content is connected with existing knowledge, presented in different forms, and linked to emotions or perspectives for action. Social and motivational factors also influence the sustainability of learning processes.

A degree programme therefore places particular demands on self-responsibility in learning: not everything is taught in courses; a large part of knowledge is acquired through individual preparation, follow-up, and transfer processes. To meet these requirements, effective learning strategies are essential.

This leads to several practical strategies for successful studying:

-

Active processing: Content should not simply be read or listened to - it needs to be processed actively. This can be done by highlighting, summarising, visualising, discussing or applying ideas. Active engagement improves understanding and memory retention.

-

Regular revision: Repetition helps anchor information in long-term memory. Spaced repetition is far more effective than cramming. Revisions should be spread over time and tailored to individual learning rhythms.

-

Multimodal learning: Understanding improves when content is accessed through various senses and formats: reading, writing, drawing, listening, speaking, or even moving. Switching modalities creates new perspectives and strengthens memory.

-

Application-oriented learning: Connecting learning to real questions, practical challenges or everyday situations enhances relevance and makes it easier to remember.

-

Linking to prior knowledge: New ideas are stored more effectively when they relate to what is already known. It helps to consciously activate relevant prior knowledge before diving into new material.

-

Learning from mistakes: Errors are not failures - they are valuable learning tools. They highlight gaps in understanding and guide improvements. Testing oneself and learning from feedback leads to stronger learning outcomes.

-

Social learning: Studying with others - through discussion, explanation or comparison - broadens perspectives and boosts motivation. Collaborative learning often leads to deeper understanding.

-

Emotional anchoring: Emotions affect attention, motivation and memory. Learning environments that feel meaningful, encouraging and empowering improve knowledge retention.

-

Reflection-based learning: Regular reflection enhances awareness of how one learns. By thinking about what worked, what didn’t, and why, learners develop metacognitive skills that support sustainable learning.

Change of perspective: Learning journal as a reflection and development tool

One powerful method to apply these strategies is keeping a learning journal. This tool supports structured reflection and can be used daily, weekly or after specific learning activities - in digital or analogue form, freely written or guided by specific categories.

A learning journal supports self-regulation, metacognitive awareness and long-term learning habits. It combines reflection and planning, makes learning paths visible, and includes all elements typically associated with a (learning) portfolio. This includes documenting progress, showing learning outcomes, analysing how a result was achieved, and reflecting on mistakes, feedback and improvement processes. In this way, the journal becomes a comprehensive tool for tracking both the process and outcomes of learning.

It may include:

-

Topics and content of the learning session

-

Learning goals and steps achieved

-

Reflections on the material and open questions

-

Notes on focus, mood and motivation

-

Observations of learning patterns, distractions or barriers

-

Overview of results and partial achievements (including feedback or marks)

-

Reflections on mistakes and strategies for improvement

-

Planning of realistic and motivating next steps

Make learning your intentional process

Use multiple formats - reading, writing, speaking, sketching - to strengthen your understanding.

Plan revisions across longer time frames using methods such as spaced repetition.

Process content actively by summarising, visualising or discussing.

Keep a learning journal to reflect on your progress and challenges.

Create emotionally engaging study phases - link learning to meaning, self-efficacy and achievable goals.

6.2 Notes & Annotations - Making Thinking Visible ^ top

Notes and annotations are more than just memory aids - they are tools for understanding, organising and reflecting. Taking notes actively engages you with the content and helps structure your thoughts. The goal is not to write down as much as possible, but to capture what is relevant in a meaningful and organised way.

Notes serve different functions: they help record initial information (e.g. in lectures), condense and structure content (e.g. when reading academic texts), and prepare for exams or academic writing. To fulfil these functions effectively, notes should be reviewed, revised and systematically developed during the follow-up.

The choice of note-taking technique depends on the aim, the context and your personal preferences. The most important factor is not the method itself, but the active engagement with the content. Visual sketches, tables or summarised bullet points can be just as effective as full sentences - as long as they support mental processing and enhance clarity.

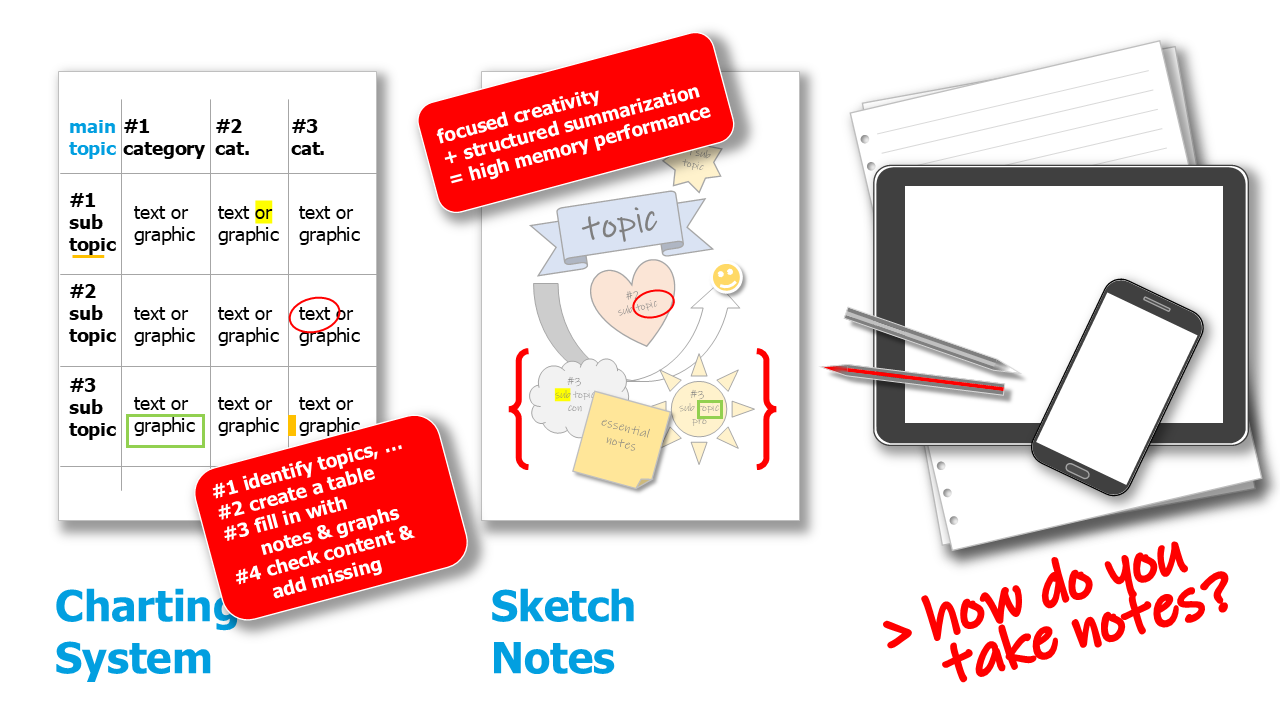

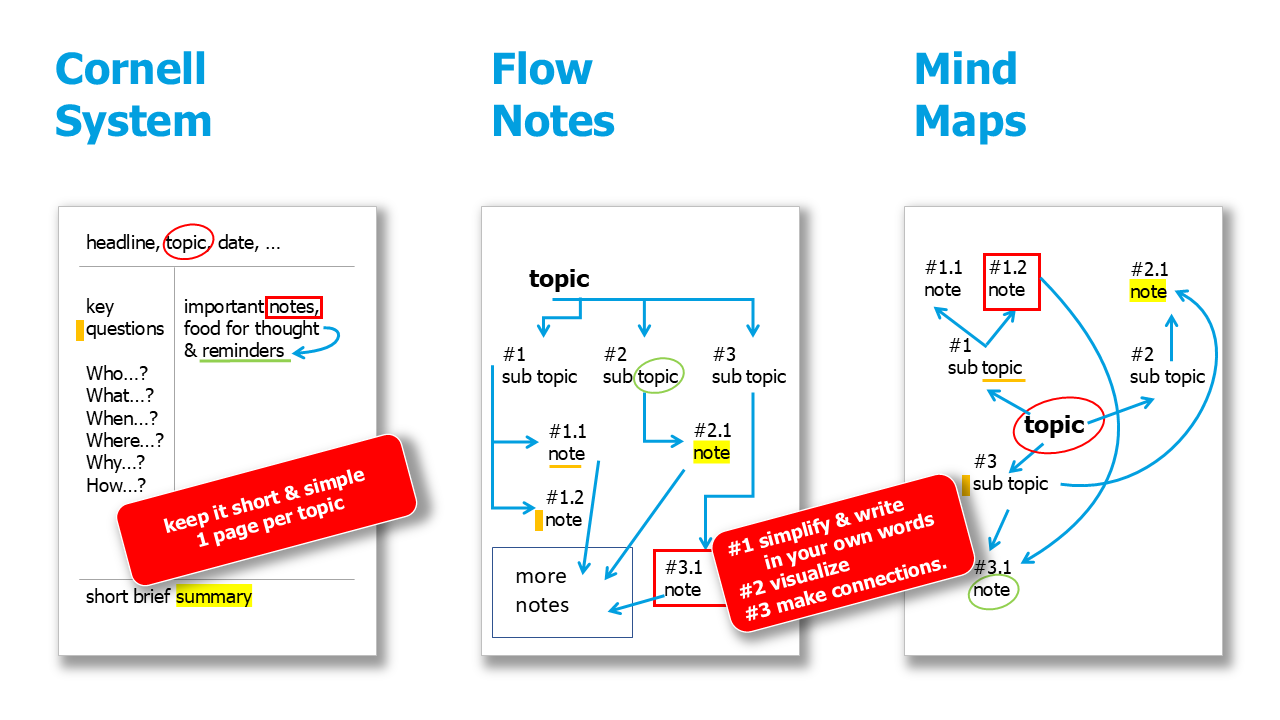

Common note-taking methods with different focuses:

| Method | Focus | Benefit | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cornell Method | Separation into notes column, guiding questions, summary | Encourages critical thinking and structured review | Lectures, exam preparation |

| Mind Map | Visual linking of key concepts | Shows relationships, encourages creative thinking | Topic overview, brainstorming |

| Charting System | Tabular structure based on categories | Enables comparison, clear structuring | Detailed analysis, literature comparison |

| Outline Method | Hierarchical bullet points | Clear structure, suitable for complex content | Structuring texts, academic elaboration |

| Sketch Notes | Combination of drawings, symbols, and text | Enhances visual learning and individual access | Personal learning summaries |

| Flow Notes | Free, associative notes with comments | Supports dynamic thinking, flexible structure | Discussion notes, reflections |

Regardless of the method used, it is important to revise notes soon after they are taken: close gaps, clarify abbreviations, highlight key points or summarise essential ideas. This turns rough drafts into useful learning materials.

Integrating subject-specific terminology, quotations and references to further reading is especially helpful - for example, when preparing academic assignments. Linking notes with learning objectives, exam formats or project requirements significantly increases their value.

Make your notes active and reflective

Develop a personal note-taking style that helps you organise and understand content.

Regularly revise your notes to secure key insights and expand your knowledge.

Use colours, symbols or tables to highlight structures and clarify connections.

Use your notes as a basis for applying knowledge, preparing for assessments or conducting academic work.

6.3 Reading Strategies - From Initial Overview to Deep Understanding ^ top

Studying involves reading. Academic articles, technical reports, legal texts or scientific literature form a central part of learning at university. But academic reading is not the same as reading fiction. The key is not simply reading more or faster, but reading with intention. Good academic reading means being able to understand the author’s message, identify important information, and reflect critically on it. That calls for different strategies depending on whether you’re looking for a quick overview, trying to extract specific content, or aiming for in-depth understanding. Reading in academic contexts is therefor not a linear activity. It usually involves multiple stages: getting an overview, focusing on selected parts, closely reading complex sections, weighing arguments and ideas, and linking the information to your own thinking.

Core aspects of a successful reading process:

-

Be clear about your goal before reading: Knowing what you are looking for helps you decide how deeply to engage with a text. Do you want a quick overview, a key definition, or a detailed understanding of the full argument? This clarity helps you manage your time and focus.

-

Use the structure of the text: Titles, headings, introductions, summaries, highlighted keywords, diagrams or bold terms often show how a text is organised. Paying attention to these signals makes it easier to spot key sections and decide what to read more carefully.

-

Selective reading over completeness: Not all texts need to be read word for word. Often it’s enough to focus on selected sections, concepts or arguments. Being able to judge what is relevant - and what is not - is an important academic skill.

-

Focus on key information while reading: Learn to spot useful content by watching for signal words, examples, and summarising phrases. This allows you to track the author’s line of reasoning and extract essential points more quickly.

-

Slow and deep reading where needed: Some parts - such as definitions, theories or detailed explanations - require close attention. These passages should be read more than once, annotated, and put into your own words. Concentration and mental effort are key.

-

Connect new content to what you already know: Learning works best when new information fits into your existing knowledge structure. Try to relate ideas from the text to past lectures, your experience, or other readings.

-

Use visual and linguistic markers: Lists, tables, figures, and formatted keywords act as orientation aids. Learning to scan for these elements can save time and help you quickly understand the organisation of the content.

-