Principles of Academic Research

methodological and epistemological principles at a glance

Summary [made with AI]

Note: This summary was produced with AI support, then reviewed and approved.

- Academic work follows fundamental principles Findings should be generalisable, based on logical reasoning and empirical testing, and remain verifiable by others. Only in this way does connectivity emerge - the integration of new results into existing debates.

- The methods differ Deduction derives hypotheses from theories, induction identifies patterns from data, abduction seeks plausible explanations for surprises. All three modes of reasoning have their place, often combined within the research process.

- Verifiability means that results can be reconstructed intersubjectively. Subjective experiences must therefore be reflected, documented, and made transparent. Objectivity remains an ideal; what matters is the controlled disclosure of ones own position.

- Good scientific practice demands more than methodological discipline. Binding principles are reliability, honesty, respect, and accountability. In addition, care, openness, proportionality, and participation matter - principles that also include ethical sensitivity, sustainability, and inclusion.

- Research distinguishes four basic types exploratory, when new fields are investigated; descriptive, when phenomena are systematically recorded; explanatory, when causes are clarified and hypotheses tested; evaluative, when measures or programmes are assessed.

Topics & Content

- Reflection Task / Activity

- Principles of Science

- 1.1 Generalisable Knowledge

- Reflection Task / Activity

- 1.2 Verification of Truth through Logic & Empiricism

- 1.2.1 Deductive Reasoning

- Typical Use Cases

- Challenges

- 1.2.2 Inductive Reasoning

- Typical Use Cases

- Challenges

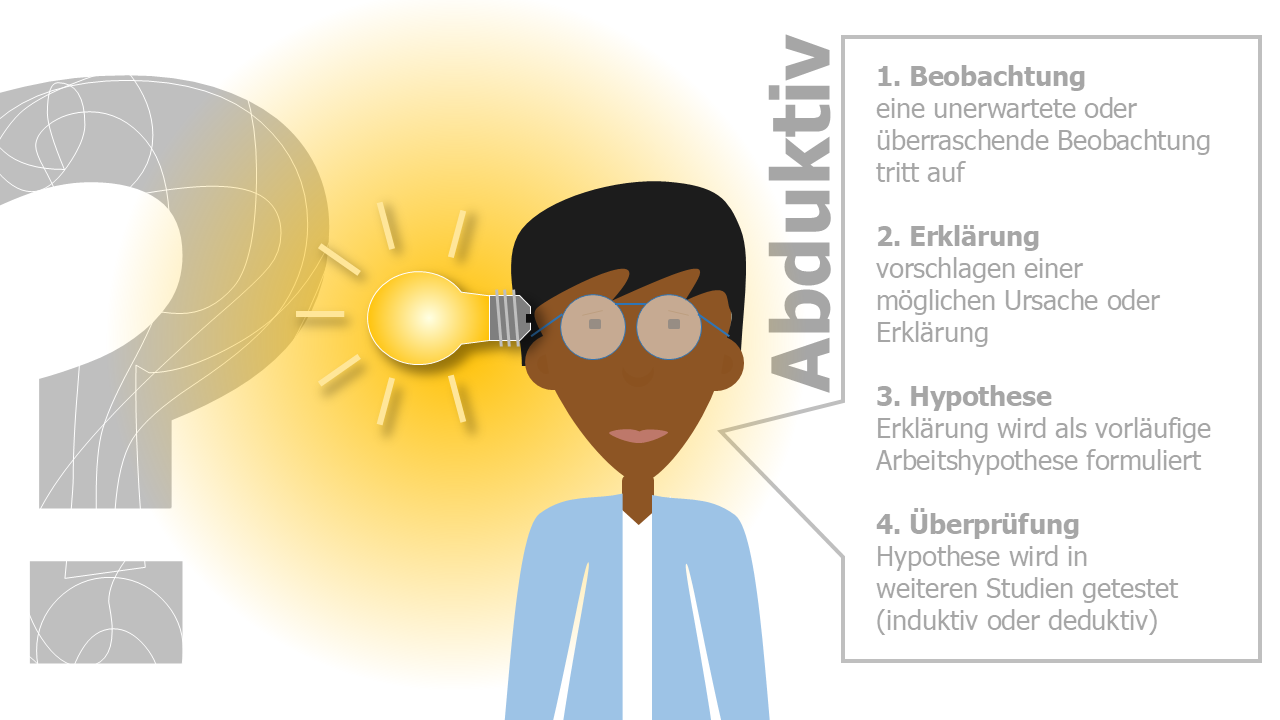

- 1.2.3 Abductive Reasoning

- Application

- Challenges

- 1.2.4 Exemplary Application in Research Methods

- Conclusion

- Reflection Task / Activity

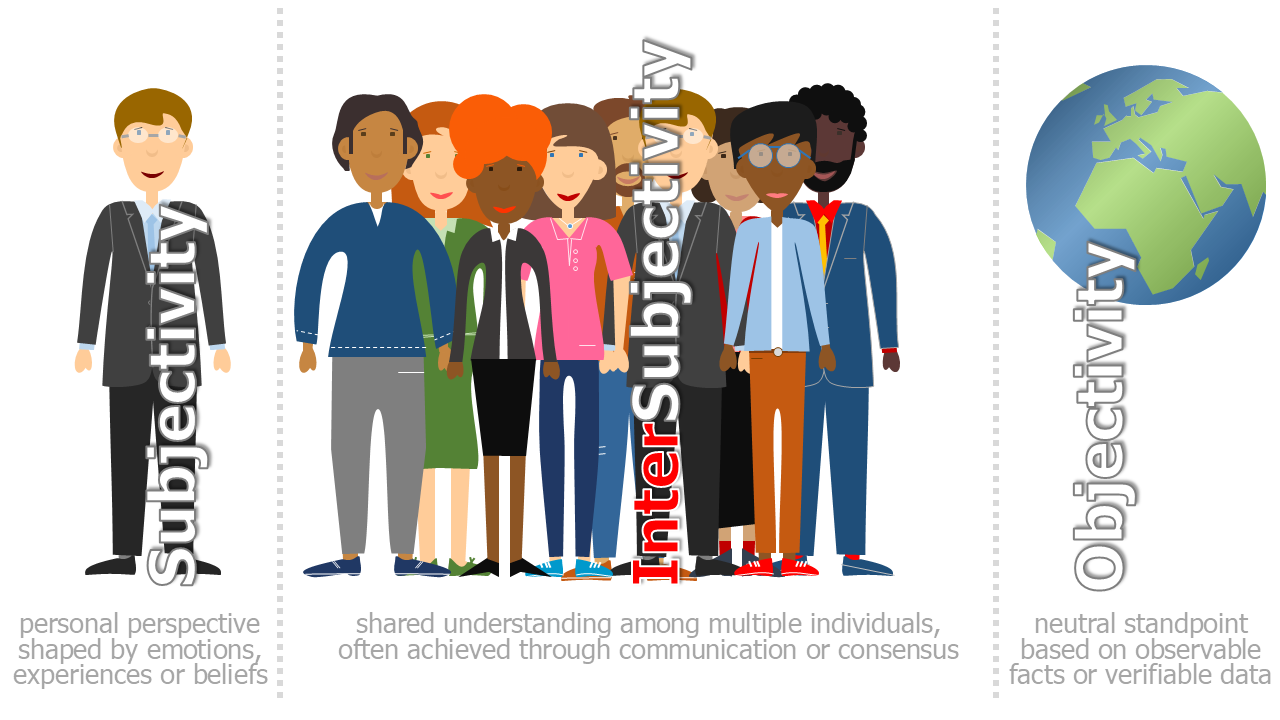

- 1.3 Verifiability

- 1.3.1 Subjectivity

- 1.3.2 Objectivity

- 1.3.3 Intersubjectivity

- Basic principles

- Applications

- Challenges

- 1.3.4 Controlled Subjectivity

- Basic principles

- Applications

- Challenges

- 1.3.5 Subjectivity - Objectivity - Intersubjectivity - Controlled Subjectivity Compared

- Reflection Task / Activity

- 2. Standards of Good Scientific Practice

- 2.1 European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity

- 2.1.1 Reliability

- 2.1.2 Honesty

- 2.1.3 Respect

- 2.1.4 Accountability

- 2.2 Complementary Principles in Research Practice

- 2.2.1 Care

- 2.2.2 Openness

- 2.2.3 Proportionality

- 2.2.4 Participation

- 2.2.5 Additional Context-Specific Principles

- Reflection Task / Activity

- 3. Types of Scientific Research

- 3.1 Overview: Exploratory, Descriptive, Explanatory, and Evaluative Research

- 3.2 Exploratory Research

- Basic Principles

- Challenges

- Examples & Application Fields

- Exemplary Methods

- Possible Applications

- 3.3 Descriptive Research

- Basic Principles

- Challenges

- Examples and Areas of Application

- Exemplary Methods

- Possible Applications

- 3.4 Explanatory Research

- Tabular Overview: Explanatory Research

- Basic Principles

- Challenges

- Examples and Application Areas

- Exemplary Methods

- Possible Applications

- 3.5 Evaluative Research

- Foundational Aspects & Characteristics

- Challenges

- Examples & Fields of Application

- Sample Methods

- Potential Applications

- Reflection Task / Activity

- 4. Bachelor's Thesis, Master's Thesis & Doctoral Dissertation Compared

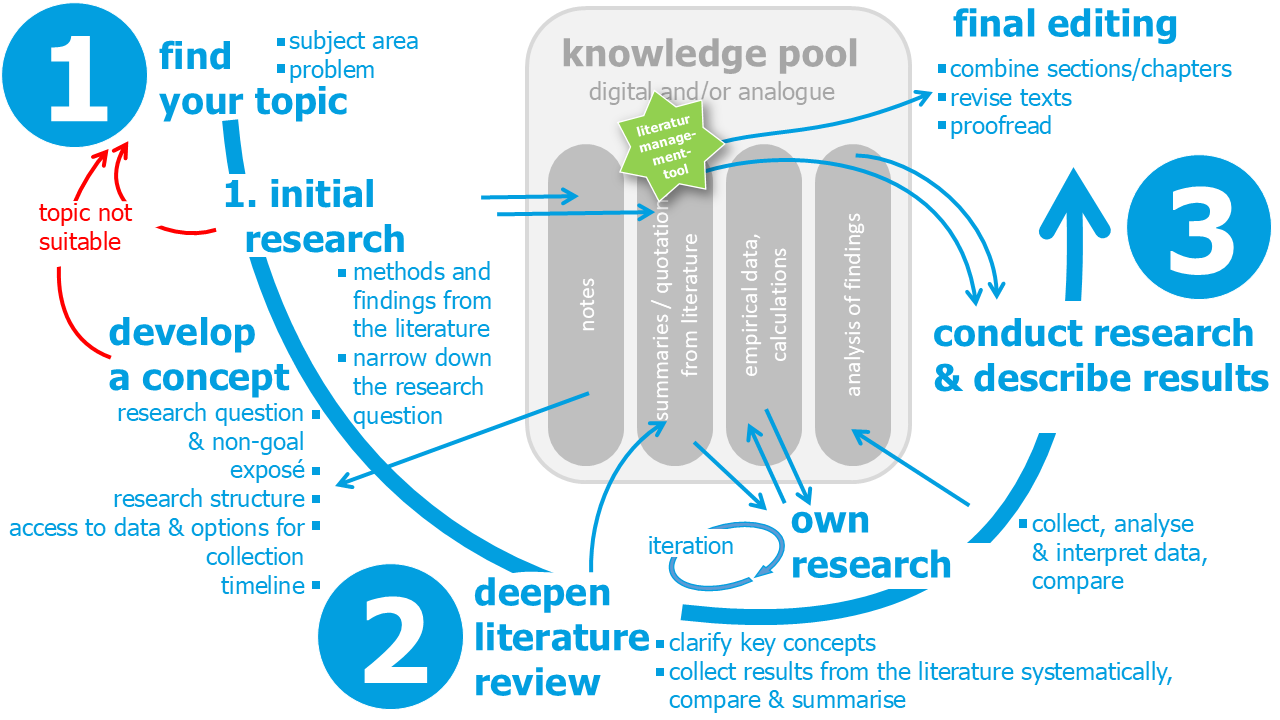

- 5. Phases of an Academic Thesis

- 5.1 Topic Selection & Concept Development

- 5.2 Research Engagement & Execution

- 5.3 Writing & Final Editing

- 6. Academic Writing = Career Advantage?!

- Reflection Task / Activity

Reflection Task / Activity ^ top

Before you read on, take a few minutes to write down what science means to you. What experiences have you had with academic work - at school, in your studies, or at work?

Important: At this stage, do not consult any specialist literature or explainer videos. The aim is to surface your own ideas - independent of official definitions or concepts.Principles of Science ^ top

Academic work follows fundamental principles that apply regardless of discipline or subject. They ensure quality assurance, enable transparency, and create a shared basis for academic discourse. By adhering to these principles, scientific findings remain coherent and verifiable.

Connectivity is a central quality criterion in academic work. It describes the capacity of research outcomes to link into existing scholarly debates - being taken up, developed further, or critically discussed by other researchers. Science is not a closed system of truths but a continuous, intersubjective process of knowledge generation, in which each new result can connect with or deliberately contrast against - existing theories, questions, concepts, and methods. Connectivity does not imply agreement with the existing literature or theoretical stance. Critical engagement, counter hypotheses, and methodological innovations can all be connective if they provide transparently and traceably reference the current state of knowledge and justify their deviation or advancement. Research that lacks connectivity remains isolated and makes little contribution to collective knowledge production.

In practice, connectivity manifests at multiple levels:

-

conceptual: key terms are clearly defined and positioned in relation to other concepts.

-

theoretical: existing models are adopted, modified, or refuted.

-

methodological: employed methods are documented and compared with established standards.

-

empirical: findings are presented so that they can be compared with other studies or used to confirm, extend, or nuance existing results.

In interdisciplinary research, connectivity is especially important: findings must be formulated so that they remain comprehensible across disciplinary boundaries. This demands conscious reflection on language use, reference theories, and the differing knowledge interests of various fields. Ultimately, connectivity is closely linked to transparency and reproducibility in academic work. Only when research processes, arguments, and conclusions are openly disclosed can others build upon them - through replication, further development, or critique. Connectivity forms the communicative foundation of academic work: insights should not remain isolated but be embedded in existing debates and made accessible for others to develop further. Achieving this connectivity requires adherence to certain fundamental principles that safeguard the quality and robustness of scholarly claims. Three central principles lie at the heart of this framework:

-

Generalisable knowledge: research must extend beyond single cases to produce systematically justified statements.

-

Logical and empirical rigour: combining reasoned argument with empirical verification ensures conclusions are theoretically grounded and supported by observation or data.

1.Reproducibility: other researchers must be able to trace, verify, or replicate the methods, reasoning steps, and results.

These three principles constitute the methodological and epistemological scaffolding that makes connectivity possible. Only when claims are valid, logically consistent, and verifiable can they enter the academic dialogue and serve as the basis for confirmation, extension, or challenge.

The principles of science form the shared foundation for scholarly engagement.

1.1 Generalisable Knowledge ^ top

A key aim of scientific research is to produce findings that go beyond individual cases. Science seeks generalisability - that is, statements that are transferable to other, comparable situations. When a single case is used to support a scientific argument or illustrate a hypothesis, it must be carefully assessed for its exemplary character. This means it should be selected and presented in such a way that it allows conclusions to be drawn about a broader group of cases or phenomena. Only then can genuinely generalisable knowledge be achieved.

Academic writing differs above all through its aim of generating generally valid knowledge, compared to other text types such as discussion essays or expert reports and professional statements in practice. The following table provides a structured comparison:

| Feature | Argumentative Essay | Expert Report / Opinion | Academic Paper |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Critical engagement with a topic; forming a reasoned opinion | Assessment of a specific situation or measure | Generation of new, scientifically grounded insights addressing a defined question or research gap |

| Basis | Argumentative structure with pro and con perspectives | Professionally grounded assessment based on standards, data, or expert knowledge | Theories, models, empirical data, or systematic literature analysis; methodologically guided |

| Context of Use | General educational discourse | Case-specific, e.g. in engineering, medicine, law | Research context; transferable to other cases |

| Structure / Argumentation |

|

|

|

| Position of the Author | Personal viewpoint encouraged, often in the conclusion | Professional assessment with a personal-expert position | Personal opinion is secondary; emphasis on objective, verifiable reasoning based on theory and data |

| Language Style | Factual, with rhetorical elements | Professionally factual, partly legal or technical | Scientifically precise, objective, and neutral |

| Use of Sources |

|

|

|

The ability to work scientifically goes beyond simply gathering information. It requires structuring content in a methodologically sound and transparent way, embedding it into a broader system of knowledge. There is a difference between an argumentative text, an expert report with a professional judgement, and an academic paper aimed at generating new knowledge or critically evaluating existing findings.

Science is a dialogical process. It thrives on making findings transparent, subjecting them to critical discussion, and embedding them in existing theories and research frameworks. Only then can knowledge unfold its relevance beyond the individual case - knowledge that is, in short, connectable.

One term often mentioned in this context is representativeness. However, this is not synonymous with generalisability. Representativeness is a methodological concept, particularly relevant in quantitative research. It refers to the extent to which a sample reflects the characteristics of a larger population, e.g. in standardised surveys, secondary data analysis using large datasets, or simulations modelling real system behaviours. The demand for representativeness applies whenever results are to be generalised to a defined target population. Depending on the research design, this may also be relevant in interview studies - for instance, when standardised guide-based interviews are conducted with randomly selected participants. Case studies, too, can aim for theoretical representativeness by strategically selecting typical, extreme, or contrasting cases (theoretical sampling). In modelling and simulation, representativeness depends on whether the model is designed to generate generalisable conclusions about a population or system.

Generalisability, on the other hand, is a broader epistemic aim. It can be justified in various ways depending on the research approach:

- quantitatively through statistical representativeness,

- qualitatively through analytical generalisation, theoretical saturation, or typology building,

- conceptually or theoretically through logical coherence and conceptual clarity.

Conclusion: Representativeness is one possible means of empirically supporting generalisable findings - especially in quantitative studies. However, it is neither universally required nor a guarantee of scientific quality. Non-representative studies - such as case studies, qualitative interviews or exploratory simulations - can also generate connectable and theoretically significant insights, as long as they are systematically reasoned, transparently documented, and contextually framed.

Reflection Task / Activity ^ top

Find one example each of an argumentative essay, an expert opinion, and an academic paper - either online or from your previous academic or professional experience.

For each example, note:

- What was the aim and context of the text?

- How was it structured?

- What sources were used?

- How did the text handle subjective judgements?

Then compare your three examples:

- Where do you see the main differences?

- Where do you notice similarities?1.2 Verification of Truth through Logic & Empiricism ^ top

In academic research, statements are not simply asserted; they must be systematically justified. Scholars therefore need to ask themselves on what basis their reasoning rests and how it can be verified. At this point, two fundamental principles become relevant: logic and empiricism. By applying logic, thoughts can be structured and conclusions drawn consistently from existing assumptions. Empiricism, in contrast, refers to observations, measurements, or experiences. These two principles are not opposed to one another but rather interact and complement each other. In scientific practice, this interplay becomes particularly clear through three methods: - deduction, in which hypotheses are derived from theories

- induction, in which new connections are established from empirical observations

- abduction, in which a surprising observation leads to a plausible explanation.

The three approaches differ with regard to their starting point, their type of justification, and their role in the research process - depending on whether one moves from a general theory to specific cases (deductive), from specific observations to general statements (inductive), or from a single observation to an initial plausible explanation (abductive).

The type of research question (e.g. open or closed) is not decisive for this distinction. What matters is how the reasoning process is structured.

The following overview contrasts the three modes of reasoning and highlights central differences regarding their starting point, purpose, evidential strength, and academic function. The examples illustrate how each form of logic is applied in research practice.

| Aspect | deductive approach | inductive approach | abductive approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direction of reasoning | From the general to the specific | From the specific to the general | From an observation to the most plausible explanation |

| Starting point | Theory, model or assumption | Observations, experience, data | Surprising or unexpected observation |

| Purpose | To test or apply an existing theory | To identify new patterns, to develop hypotheses | To formulate an initial, plausible working hypothesis |

| Evidential strength | Logically compelling if the theory is correct | Probable, but not certain | Possible and plausible, but not yet confirmed |

| Research function | To test hypotheses, confirm or refute theories | To generate hypotheses, develop theories | To develop new ideas and explanations |

| Example | "If sustainable buildings increase user satisfaction, then people in green buildings should be more satisfied." | "Many users report higher satisfaction in green buildings - perhaps this is related to building quality." | "The lawn is wet - it has probably rained." |

1.2.1 Deductive Reasoning ^ top

Deductive reasoning is an epistemological process - that is, a way of reasoning concerned with how knowledge is generated and justified - in which specific conclusions are logically derived from general principles. This approach is often described as "top-down" because it proceeds from a general theory or hypothesis to specific predictions or conclusions. Deductive inferences are logically necessary: if the general principles are true, then the derived conclusions must also be true.

If A is true and B falls under A, then B must also be true.

In scientific practice, this means that a theory or model is used to formulate questions or hypotheses that can subsequently be tested empirically. The validity of deductive reasoning, however, depends solely on the correctness of the premises and the logical structure - not on empirical observation.

-

General statement or theory:

Deductive reasoning begins with a general statement or theory that is grounded in established principles or prior scientific knowledge. This general statement is referred to as the premise and forms the basis for the deductive process. -

Derived conclusion:

The purpose of deductive reasoning is to derive specific predictions or conclusions from the general premise. These conclusions are, in principle, logically necessary: if the premise is true, the conclusion must also be true.

Typical Use Cases ^ top

-

Hypothesis formulation: Researchers often use deductive reasoning to generate hypotheses. A hypothesis is a specific prediction based on a general theory. Deduction enables researchers to formulate expectations and then test these through observation or experimentation.

-

Theory testing: Deductive reasoning is employed to test and validate existing theories. When predictions derived from a theory are confirmed by empirical data, this supports the theory.

-

Falsification: Deductive reasoning also allows for falsification. If predictions derived from a theory are contradicted by empirical evidence, the theory may need to be revised or rejected.

Challenges ^ top

-

Assumptions: Deductive reasoning relies on the accuracy of its premises. If these are flawed, the conclusions will also be invalid.

-

Complexity: In complex systems or real-world contexts, conclusions may not be as straightforward as theoretical examples suggest. Deductive reasoning can be more difficult to apply in such situations.

-

Uncertainty: Many areas of research involve uncertainty and variability. Deductive logic often abstracts from such factors and may not adequately reflect the nuance of empirical data.

1.2.2 Inductive Reasoning ^ top

In contrast to deduction, inductive reasoning is based on specific observations and leads to general conclusions. This approach is often described as "bottom-up," as it proceeds from concrete data to general patterns or regularities. Inductive conclusions are not logically necessary, as they rely on probability and generalisation.

-

Observations and data:

The process of inductive reasoning begins with careful observation and data collection. Researchers gather information on the phenomena or events they wish to investigate. -

Identification of patterns or trends:

Once sufficient data has been collected, researchers analyse it to identify patterns or trends. These may relate to recurring characteristics or behaviours. -

Generation of conclusions:

Based on the identified patterns or trends, researchers formulate general conclusions or hypotheses. These conclusions are probabilistic in nature - that is, the patterns observed are likely, though not guaranteed, to apply to future cases or situations.

Typical Use Cases ^ top

-

Pattern discovery: Researchers use inductive reasoning to detect patterns or trends in data. This is particularly useful in exploratory research, especially when little prior knowledge is available about a phenomenon.

-

Hypothesis generation: Patterns identified through inductive reasoning can serve as a basis for generating hypotheses, which may later be tested using deductive methods.

-

Theory development: Inductive reasoning can contribute to the development or refinement of theories. When repeated observations indicate consistent patterns, broader theoretical frameworks may be constructed.

Challenges ^ top

-

Generalisability: Inductive reasoning involves generalising from specific observations. However, these generalisations may not hold true in all contexts.

-

Sample representativeness: The strength of inductive conclusions depends heavily on the representativeness of the sample. A non-representative sample can lead to distorted or unreliable conclusions.

-

Unforeseen variables: Inductive conclusions may be affected by unknown or uncontrollable variables that were not accounted for in the analysis.

1.2.3 Abductive Reasoning ^ top

In contrast to deduction and induction, abductive reasoning aims to find a plausible explanation for a surprising or unexpected observation. This approach is often described as an "inference to the best explanation". Abduction does not provide logical certainty or a general rule, but rather an initial, provisional interpretation that serves as a starting point for further research.

-

Unexpected observation:

The process of abductive reasoning begins with an observation that cannot easily be explained with existing knowledge. Researchers encounter a phenomenon that raises questions. -

Plausible explanation:

On the basis of this observation, they formulate a possible explanation. This explanation is not conclusive, but it appears reasonable and coherent in the given context. -

Working hypothesis:

Abductive reasoning leads to a hypothesis that links the observation with the explanation. This hypothesis is provisional and must be examined further through inductive or deductive methods.

Application ^ top

-

Exploratory research: Abduction is especially useful when little prior knowledge about a phenomenon is available. Researchers can develop initial explanations that are later tested systematically.

-

Hypothesis generation: Abductive reasoning makes it possible to formulate new hypotheses that are grounded in surprising or unexplained observations.

-

Qualitative research: In approaches such as Grounded Theory, abduction is used to derive preliminary interpretations from interviews or case studies, which are then further refined and tested.

Challenges ^ top

-

Uncertainty: Abductive reasoning is neither conclusive nor highly probable; it is only plausible. Later findings may prove it wrong.

-

Subjectivity: What counts as plausible often depends on the researcher’s background knowledge and perspective.

-

Verifiability: Abduction alone does not provide verification. Only subsequent inductive and deductive testing can make an abductive hypothesis academically robust.

1.2.4 Exemplary Application in Research Methods ^ top

The following table uses typical research methods and research designs to show the application of deductive, inductive and abductive reasoning:

| Method | Deductive application | Inductive application | Abductive application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire | Questions are based on theoretical concepts or previous studies. Aim: to test a hypothesis. | Exploratory items in a pilot study to identify relevant topics. | Unexpected responses lead to a new, provisional hypothesis that is explored in further studies. |

| Interview (guide) | Structure and question logic follow a theory or conceptual assumptions from the literature. | Conversations without a fixed structure. Aim: to discover new perspectives; categories emerge only during analysis. | Individual surprising statements by respondents inspire new interpretations or first explanatory approaches. |

| Simulation | Model assumptions are based on theoretical knowledge or empirically established relationships. | Model is developed from existing data sets (e.g. through data-driven analysis or machine learning). | Unexpected simulation results serve as a starting point for formulating new hypotheses about system relationships. |

| Case study | Case selection and analysis are guided by a theory or typical hypotheses from the literature. | Case study is used to investigate complex phenomena openly. Theory emerges during analysis. | Distinctive features in a case lead to an initial, plausible explanation that can be tested in further cases. |

| Secondary data analysis | Literature-based hypotheses are tested systematically using available data. | Aim is to explore existing data, e.g. to identify unexpected patterns or relationships. | An unusual data pattern is interpreted as a clue to a new relationship and formulated as a hypothesis. |

Conclusion ^ top

Deductive, inductive, and abductive reasoning each have different strengths - all three are important in academic research:

- Deduction: useful when theories or models already exist and need to be tested or applied.

- Induction: suitable when a topic is new or when the aim is to explore it openly to identify relevant aspects.

- Abduction: helpful when a surprising observation requires an initial plausible explanation, which can then be tested further.

In many research projects, these approaches are combined:

- first abductively, to interpret an unexpected observation and propose an initial hypothesis,

- then inductively, to collect further data and identify patterns,

- and finally deductively, to test the hypotheses systematically.

Reflection Task / Activity ^ top

Research what is meant by "deduction", "induction", and "abduction" in academic work.

Develop an example from your own field for each - one that follows a deductive approach, one that is inductive, and (if possible) one that is abductive.

Explain in your own words what the difference is - and for which purpose you would use each approach.

1.3 Verifiability ^ top

Scientific work is founded on the verifiability of knowledge. This is enabled by intersubjective reasoning: a complex matter must be comprehensible and checkable by multiple observers. Since absolute objectivity is rarely attainable, intersubjectivity is considered a central quality criterion.

1.3.1 Subjectivity ^ top

Subjectivity refers to personal perspectives shaped by individual experiences, emotions or values. Subjective statements are not universally valid and usually cannot be independently verified.

-

Subjective judgements are based on personal perception.

-

They are not necessarily supported by data or facts.

-

Different individuals may interpret the same phenomenon differently.

1.3.2 Objectivity ^ top

Objectivity refers to an ideal state of scientific knowledge where statements are entirely independent of the person making them. Objective statements must be reproducible under identical conditions, and understandable to anyone, regardless of individual background or perspective.

-

Objective statements hold true regardless of observer or context.

-

They are fully verifiable and consistently reproducible.

-

Objectivity is aspired to in science, but fully attainable only in certain fields (e.g. mathematics, physics).

1.3.3 Intersubjectivity ^ top

Intersubjectivity denotes shared understanding between multiple subjects. It is the main criterion for scientific verifiability: a finding is considered valid when it can be independently reconstructed by others - especially within the scholarly community.

Basic principles ^ top

-

Communication and documentation: Results are prepared so that others can evaluate and understand them.

-

Shared understanding: Terms, methods and interpretations are aligned within the scholarly community.

Applications ^ top

-

Peer review: Scholars assess texts for consistency, transparency and academic quality.

-

Scientific discourse: Knowledge emerges through exchange - disagreement and consensus are integral to the process.

Challenges ^ top

-

Cultural and linguistic contexts: Varied understandings may lead to misinterpretations.

-

Limited perspectives: A homogeneous research team may offer a narrow horizon.

-

Unconscious biases: Researchers, too, hold preconceptions that shape interpretation.

-

Complex phenomena: Even with full disclosure, some interpretations remain contested.

1.3.4 Controlled Subjectivity ^ top

Personal experiences, values or theoretical positions influence how data are gathered, analysed and presented. Rather than eliminating these influences, scientific practice demands their explicit reflection and disclosure. This is known as controlled subjectivity.

Basic principles ^ top

-

Self-reflection: Researchers question their own perspective and disclose personal assumptions, interests or experiences.

-

Transparent documentation: Decisions regarding methodology, scope or interpretation are systematically justified.

Applications ^ top

-

Subjective influences are not avoided but made visible and critically reflected upon.

-

Readers can trace how results emerged and better assess their validity.

-

Controlled subjectivity enhances academic integrity and trustworthiness.

The following text modules provide practical examples of how controlled subjectivity can be implemented and made transparent throughout the research process - including the reflection of one's own role, the conduct of interviews, data interpretation, and methodological documentation.

Reflecting on the Researcher’s Role:

Within the study, the researcher did not operate solely from an external, observational perspective but was also actively embedded in the project context. This dual role - as both researcher and participant - enabled deeper insights into internal processes, but also carried the risk of unintentionally influencing data collection and interpretation.

To minimise potential bias, the researcher’s positionality was regularly reflected upon in line with the principle of controlled subjectivity. Key decisions, such as the selection of data, the formulation of questions, and the analytical procedures, were systematically documented and transparently justified.

Potential Influence on Data Collection:

- The researcher consciously reflected on their personal proximity to participants and familiarity with the research context, as these factors may influence participants’ responses (e.g. through social desirability or implicit role expectations).*

To counteract such effects, care was taken to use open, non-leading questions during interviews, maintain neutral body language, and adopt a reserved, non-directive manner. The research role was clearly communicated in advance to clarify expectations and avoid role conflicts.

Potential Influence on Interpretation:

Data interpretation was conducted with ongoing reflection on possible preconceptions, which might arise from disciplinary background, project involvement, or personal experience.

Alternative interpretations were actively considered, and the analysis was complemented by peer feedback. Interpretations closely aligned with personal perspectives were explicitly marked to strengthen transparency and reveal potential interpretive frameworks.

Transparency and Academic Integrity:

Rather than being excluded, personal perspectives and theoretical orientations were explicitly acknowledged as part of the analytical process. These influences were made transparent through systematic documentation (e.g. reflexive notes, methodological justifications), thereby supporting research integrity and enhancing the trustworthiness of findings.

Challenges ^ top

-

Blind spots: Personal positions are not always consciously recognised.

-

Role conflict: Researchers may simultaneously be observers, participants or stakeholders - requiring careful handling.

-

Lack of training: Dealing with subjectivity is often not formally taught in research practice.

-

Limits of disclosure: Not all influences can be fully made transparent or adequately expressed.

1.3.5 Subjectivity - Objectivity - Intersubjectivity - Controlled Subjectivity Compared ^ top

A comparative table illustrates the four concepts and typical examples of their application in scientific contexts. It supports reflection on the levels of positionality and verifiability in scholarly claims.

| Level | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Subjectivity | Personal perception shaped by individual experience and emotion. | "I feel the winters in the Alps are milder today than in the past." |

| Objectivity | Statement that is independent of the observer and reproducible under identical conditions. | "Temperature measurements over 30 years show a significant decline in snow days." |

| Intersubjectivity | Agreement within a scientific community on terms, methods and results. | "Climate researchers worldwide agree through data analysis and discussion on anthropogenic climate change." |

| Controlled Subjectivity | Reflexive and transparent disclosure of individual perspectives to enhance verifiability. | "As I was directly involved in the organisational decision‑making, I transparently reflected on my role and its influence in the research process." |

Reflection Task / Activity ^ top

Research the term "intersubjectivity" and distinguish it from "subjectivity" and "objectivity".

Consider: Why is intersubjectivity so important for scientific verifiability? Find an example from your field where intersubjectivity plays a role.2. Standards of Good Scientific Practice ^ top

Science thrives on trust: trust in research quality, in the integrity of researchers, and in the verifiability of findings. To uphold this trust, the international scientific community has developed a widely accepted consensus on standards and guidelines for Good Scientific Practice (GSP). These standards define how research should be planned, conducted, documented, and communicated - and where misconduct begins. Universities, funding bodies, and research institutions issue corresponding guidelines, for instance:

-

Hochschulkonferenz AG "Research Ethics / Research Integrity". (2020). Praxisleitfaden für Integrität und Ethik in der Wissenschaft. Bundesministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Forschung. https://www.bmfwf.gv.at/dam/jcr:51530238-8ece-4dde-808e-0ad0c9107f6b/2020-10-20_Praxisleitfaden für Integrität und Ethik in der Wissenschaft_engl_.pdf

-

Österreichische Agentur für wissenschaftliche Integrität (Hrsg.). (2019). Richtlinien der Österreichischen Agentur für wissenschaftliche Integrität zur Guten Wissenschaftlichen Praxis. https://oeawi.at/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/OeAWI_Broschüre_Web_2019.pdf

-

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Hrsg.). (2022). Leitlinien zur Sicherung guter wissenschaftlicher Praxis- Kodex (1.1). https://zenodo.org/records/14281892/files/en_Guidelines for Safeguarding Good Research Practice_Code of Conduct_Version 1.2.pdf

-

ALLEA - All European Academies. (2023). The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity. https://doi.org/10.26356/ECoC

2.1 European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity ^ top

The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity, developed by ALLEA (All European Academies), is a widely recognised framework. Founded in 1994, ALLEA unites over 50 national science academies across more than 40 European countries - including the Austrian Academy of Sciences, the German Leopoldina, and the UK’s Royal Society. ALLEA’s objectives include fostering scientific exchange in Europe through:

-

Advising on science policy,

-

Promoting research freedom and integrity,

-

Developing shared standards for good scientific practice.

The European Code of Conduct - drafted in collaboration with the European Commission - outlines four central principles:

| Principles | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Reliability | Research must be methodologically sound, carefully planned and transparently conducted. |

| Honesty | All findings and statements must be presented truthfully, completely and openly. |

| Respect | The rights, dignity and interests of humans, animals, the environment and cultural heritage must be respected. |

| Accountability | Researchers bear responsibility for their work and its consequences - from planning through publication. |

The Code also provides practical guidance on:

-

Publication ethics and authorship roles,

-

Data management and archiving,

-

Peer review, evaluations, and mentoring,

-

Addressing misconduct, conflicts and whistleblowing.

It serves both as a behavioural standard for researchers and as a guideline for institutions, ethics committees and funding agencies.

2.1.1 Reliability ^ top

Research should be systematic, methodologically rigorous and conducted with utmost care. Scientific insights must be based on transparent, verifiable and consistent methods - not chance or arbitrariness.

-

Recognised methodology: Researchers select appropriate methods corresponding to the research question and justify these decisions transparently. Methods must be disciplinary standard and well-reasoned.

-

Transparency in the research process: Every stage - from data collection through analysis to interpretation - is documented so others can understand, evaluate or replicate the process. Preliminary decisions (e.g. case selection, data exclusion) must be traceable.

-

Reproducibility & repeatability: Studies should be replicable under similar conditions. This also includes includes listing all materials used, software versions, and analysis criteria.

-

Consistency and plausibility: Results should remain comparable across tests, data sources or time points. Any inconsistencies must be explicitly discussed rather than concealed.

2.1.2 Honesty ^ top

Integrity is foundational to scientific work. Researchers must communicate transparently, impartially and fully throughout the research process.

-

Transparency towards third parties: All relevant information - such as study design, funding sources and potential conflicts of interest - must be disclosed. Concealment is unacceptable.

-

Unbiased presentation of data and findings: Results should be presented objectively, without deliberate distortion in favour of hypotheses.

-

Comprehensive reporting: Unexpected, insignificant or contradictory findings must also be reported. Omitting selective data (reporting bias) violates research integrity.

-

Fair authorship and citation: Contributions from others must be properly credited. Ghostwriting, honorary authorship or plagiarism are impermissible. Those who did not make substantial contributions should not be listed as authors.

2.1.3 Respect ^ top

Research never occurs in a vacuum - it concerns people, animals, society, and the environment. Ethical awareness and responsibility are required at all times.

-

Respect for human dignity: Participants must provide voluntary, informed consent. Privacy and confidentiality must be protected.

-

Avoidance of harm: Research must not cause psychological or physical harm - to respondents, observed individuals, affected groups or society at large.

-

Environmental responsibility: Research should consider ecological effects, use resources responsibly, and avoid unnecessary emissions or strain.

-

Cultural and historical sensitivity: Respect and sensitivity are necessary when working with heritage, historic sites or socially sensitive topics.

-

Animal welfare: The 3Rs must be observed: Replace (use alternatives where possible), Reduce (minimise the number of animals), Refine (minimise suffering).

2.1.4 Accountability ^ top

Scientific research entails responsibility - to the scholarly community, the public, one’s institution and future generations.

-

Diligent documentation and archiving: Data, analysis steps, materials and versions are recorded in a way that ensures long-term accessibility and scrutiny. Empirical studies must comply with data retention requirements.

-

Disclosure of funding and interests: Funding sources, institutional ties and potential conflicts must be declared, especially in evaluations, industrial research or consultancy.

-

Handling of errors: Mistakes are not taboo but part of the scientific discourse. Errors should be acknowledged openly, and published findings corrected or retracted if necessary.

-

Quality culture and mentoring: Senior researchers bear responsibility for transmitting good scientific practice to students, doctoral candidates and colleagues. Ethics training, supervision and discussion are integral to scholarly qualification.

2.2 Complementary Principles in Research Practice ^ top

In addition to the four core principles of the ALLEA Code (Reliability, Honesty, Respect, and Accountability), many national and discipline-specific guidelines include further principles and attitudes that characterise reflective scientific practice. These expand or refine the ALLEA principles to address contexts where particular considerations - such as ethical sensitivity, stakeholder inclusion, or sustainability - are key.

2.2.1 Care ^ top

Care entails methodical discipline, reflection and precision at every stage of scientific work:

-

Formulating the research question: The question is clearly articulated, justified, and developed without unexamined pre-assumptions.

-

Conducting data collection: The chosen method is implemented with care - adhering to protocols, maintaining precise records and applying appropriate prompts.

-

Analysis & interpretation: Interpretation is transparent and logical; statements are grounded in data, not speculation or wishful thinking.

-

Citation & source usage: Ideas, arguments or findings from others are accurately cited; secondary sources are clearly identified.

-

Data handling: Research data are carefully stored, versioned and protected against loss or unauthorised access.

2.2.2 Openness ^ top

Openness denotes a willingness to communicate research transparently, share findings, and remain receptive to criticism or alternative perspectives:

-

Process and goal transparency: Study design, assumptions, methodological choices and limitations are openly disclosed.

-

Access to results: Findings are published in open formats where possible (e.g. Open Access).

-

**Access to data: Data are documented and shared to enable reuse, verification or comparison (e.g. Open Data).

-

Willingness to engage in dialogue: dissenting views are welcomed as opportunities to broaden understanding.

-

Interdisciplinary collaboration: researchers actively seek and maintain cooperation across disciplinary boundaries.

2.2.3 Proportionality ^ top

Research must be ethically justifiable. Proportionality implies that the expected benefits are appropriate relative to the effort, risks or burdens involved:

-

Consideration of sensitive topics: Personal or distressing questions are only asked if essential to the research aims.

-

Reducing participant burden: Those involved are not subjected to unnecessary physical or psychological stress.

-

Responsible use of resources: Time, finances, materials, and environmental resources are used efficiently.

-

Ethical evaluation in animal research or interventions: alternatives are considered and unnecessary repetition avoided.

2.2.4 Participation ^ top

Participation involves actively involving individuals or groups directly or indirectly affected by the research, thereby enhancing relevance, ethical integrity and acceptance.

-

Involvement in planning: Stakeholders and affected groups contribute to topic selection or formulation of research questions.

-

Collaborative data collection and analysis: Data gathering and interpretation involve participants (e.g. community-based research).

-

Transparent communication of results: Findings are presented in accessible formats and shared with participants.

-

Recognition of experiential knowledge: Subjective experiential insights are respected as valuable contributions to analysis.

2.2.5 Additional Context-Specific Principles ^ top

Depending on the field, institution or research context, additional principles may further support scientific integrity and societal responsibility:

-

Sustainability: Research is designed with ecological, social and institutional longevity in mind.

-

Transdisciplinarity: Systematic collaboration between academia and practice is actively pursued.

-

Diversity and inclusion: Research encompasses varied perspectives and avoids discrimination or systematic exclusion.

-

Responsible use of technology: New technologies are assessed not only for efficiency but also for social implications, power relations or ethical risks (e.g. AI, surveillance, genetic engineering).

These additional principles reinforce scientific responsibility and ethical grounding - especially in transdisciplinary and practice-oriented fields such as sustainability, public health research and social innovation.

Reflection Task / Activity ^ top

Examine two different codes of scientific conduct (e.g. ALLEA, DFG, OeAWI).

Which principles are shared? Which are emphasised differently? Consider how you might apply these standards concretely in your studies or research project.3. Types of Scientific Research ^ top

Academic research is a multifaceted process aimed at the systematic investigation of phenomena to generate new knowledge, test existing theories, and develop practical solutions to current challenges. Differentiating between various types of research helps to better classify research projects, understand methodological approaches, and interpret findings appropriately.

The following section introduces four core types of scientific research. Each serves a distinct function within the process of knowledge generation - from initial orientation within a topic area to evaluating the effectiveness of specific interventions. These four core types - exploratory, descriptive, explanatory, and evaluative - provide a foundational framework that reflects the research interest of a given study. Many additional types of research, such as prognostic, interventional, theoretical, or normative, either derive from or complement these fundamental forms. They are often expanded or specialised applications of the four central research logics.

3.1 Overview: Exploratory, Descriptive, Explanatory, and Evaluative Research ^ top

The four basic types of scientific research can be distinguished by their objectives, theoretical grounding, and methodological approaches. Each represents a different pathway to knowledge that can be applied depending on the research question and context. Exploratory research primarily investigates underexplored phenomena, while descriptive research aims to systematically capture existing states or trends. Explanatory research seeks to identify causal relationships and test hypotheses. Evaluative research, in turn, assesses the effectiveness or impact of actions and programmes. The following table compares key characteristics of these four research types and supports their differentiation in academic practice.

| Research Type | Objective | Theoretical Basis | Methodology | Typical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exploratory | To explore new topics, generate hypotheses | Low or open | Flexible, often qualitative | Initial insights, concepts, research questions |

| Descriptive | To systematically describe phenomena | Optional | Standardised, usually quantitative | Frequencies, distributions, status reports |

| Explanatory | To explain causes and relationships | High | Standardised, quantitative | Explanatory models, hypothesis testing |

| Evaluative | To assess interventions or programmes | Goal- or theory-oriented | Mixed methods common | Assessments (e.g. effectiveness, efficiency) |

3.2 Exploratory Research ^ top

Explores unknown territory by searching for hidden patterns in data or investigating the behaviour of a phenomenon.

Exploratory research is applied when there is little prior knowledge, no established theories, or existing explanatory models prove inadequate. Its aim is to provide orientation, develop initial explanatory approaches, and open up new research perspectives. It is particularly suitable in early project phases or when addressing complex, interdisciplinary questions.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Aims | Preliminary orientation, discovery of new patterns |

| Theoretical relation | Open or limited |

| Methodological approach | Flexible, frequently qualitative |

| Data analysis | Descriptive, structure-seeking, hypothesis-generating |

| Typical methods | Interviews, focus groups, case studies, literature reviews |

| Challenges | Limited transferability, interpretative ambiguity, lack of theoretical frame |

Basic Principles ^ top

-

Aims: Exploratory research seeks to better understand phenomena that are poorly understood or newly emerging. The goal is to gain an initial overview and identify potential influencing factors or relevant relationships.

-

Theoretical relation: Research often commences without a fixed theoretical framework. Theories or concepts emerge from collected data or are applied retrospectively to contextualise findings.

-

Flexibility: Researchers adapt their methodological approach in response to emerging data and analysis. New insights may influence subsequent phases of data collection, which is especially common in qualitative designs.

-

Epistemic interest: The aim is not to test pre-defined hypotheses, but to generate new research questions, conceptual frameworks, and hypotheses for subsequent investigation.

-

Typical methods: Commonly employed methods include narrative interviews, focus groups, ethnographic observations, alongside exploratory quantitative methods (e.g. cluster analysis, correlational patterns).

Challenges ^ top

-

Limited generalisability: Findings from exploratory studies are often context-specific. They provide initial hypotheses rather than statistically validated results.

-

Interpretive ambiguity: Due to the openness of the research process, interpretation plays a central role, requiring methodological sensitivity and transparent documentation.

-

Lack of theoretical embedding: Without grounding in existing theory, findings may remain isolated, limiting their connectivity and academic relevance.

-

Subjective bias: The researcher’s perspective is actively shaping. To mitigate bias, reflective practice and methodological safeguards (e.g. triangulation) are essential.

Examples & Application Fields ^ top

-

Identifying emerging social indicators for sustainability reporting in small and medium-sized enterprises.

-

Exploring barriers to adopting building‑related energy data within ESG reporting frameworks.

-

Capturing previously unconsidered perspectives on sufficiency strategies in corporate energy management, for example via interviews with facility managers.

-

Conducting exploratory case studies on user perceptions of service quality in modern office designs.

-

Investigating factors influencing vacancy trends in regional secondary real estate markets.

-

Interviewing technical facility managers about obstacles to digitising maintenance processes.

Exemplary Methods ^ top

-

Literature review: Systematic analysis of existing studies on sustainable land use management or ESG indicators within the real estate sector.

-

Expert interviews: Semi-structured interviews with energy consultants, property managers or sustainability officers to capture their assessments and professional experience.

-

Focus groups: Moderated discussions with diverse stakeholder groups, such as building users, investors, or planners.

-

Case studies: In-depth analysis of selected real estate projects that demonstrate innovative approaches to climate protection, energy efficiency, or user participation.

Possible Applications ^ top

Findings from exploratory research often serve as a foundation for subsequent research phases, including:

-

Development of a theoretical model that systematises the identified factors.

-

Derivation of testable hypotheses for quantitative or experimental studies.

-

Design of applied research projects, e.g. on new ESG indicators or strategies to optimise sustainability performance in building operations.

3.3 Descriptive Research ^ top

Describes phenomena precisely as they appear - without altering, explaining, or evaluating them.

Descriptive research systematically and structurally captures the current state of a phenomenon. It is employed to document characteristics, distributions, or associations without necessarily offering theoretical explanations. The aim is to generate an accurate representation of reality. Descriptive studies often serve as a foundation for subsequent analytical or explanatory research by providing essential baseline data.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Aim | Systematic description of phenomena, conditions, distributions |

| Theoretical grounding | Often present, but not essential |

| Methodological approach | Standardised, often quantitative |

| Data analysis | Statistical-descriptive (frequencies, means, standard deviations, etc.) |

| Common methods | Standardised surveys, secondary data analysis, observations |

| Challenges | No causal claims, measurement issues, risk of bias |

Basic Principles ^ top

-

Aim: The goal is to capture attributes, behaviours, or attitudes of a specific target group or research object with precision. Descriptive research is not intended to test hypotheses or explain causal mechanisms; rather, it documents what currently exists.

-

Theoretical grounding: Descriptive research can be informed by theory (e.g. through structured data collection instruments), but it is not necessarily theory-bound. Classifications, definitions, or reference values often provide orientation.

-

Methodological approach: Standardised quantitative methods are commonly used. In some contexts, structured qualitative techniques such as systematic observation or coding of open responses may also be applied.

-

Research interest: Descriptive research focuses on "how frequent", "how strong", "in which manifestations" - rather than causes. Its strength lies in producing empirically substantiated clarity and comparability.

-

Common methods: Typical methods include structured questionnaires, counts, analysis of existing datasets (e.g. energy consumption, vacancy rates), and systematic observations.

Challenges ^ top

-

No causal claims: Descriptive research does not provide causal explanations. Even if correlations are reported, no causal relationships can be inferred.

-

Measurement issues: The quality of the results depends heavily on the operationalisation. Imprecise questions, unclear categories, or poorly executed data collection can distort findings.

-

Risk of bias: Even with standardised methods, systematic errors may occur - for example, due to non-response bias in surveys or selective data availability in secondary data analyses.

-

Interpretation of data: Even without claiming causality, descriptive data must be interpreted with care. Context, data sources, and possible influencing factors must be considered.

Examples and Areas of Application ^ top

-

Assessment of average energy consumption per square metre in office buildings in Austria.

-

Descriptive analysis of user satisfaction with facility services (e.g. cleaning, indoor climate) based on standardised questionnaires.

-

Measurement of vacancy rates in the property portfolios of municipal housing providers across different regions and time periods.

-

Content analysis of publicly available ESG reports to determine the frequency of key indicators (e.g. CO2 emissions per employee).

-

Observation and documentation of workspace utilisation in co-working environments during weekdays.

Exemplary Methods ^ top

-

Online survey: Quantitative study on tenant satisfaction with energy management in residential buildings, including frequency distributions and mean values.

-

Secondary data analysis: Use of data from statistical offices, energy suppliers, or industry reports to describe market or consumption structures.

-

Structured observation: Systematic recording of space usage (e.g. meeting rooms, communal areas) in public buildings using a predefined observation grid.

-

Monitoring reports: Regular status reports on sustainability indicators within organisations or institutions, e.g. carbon footprint or water consumption.

Possible Applications ^ top

Descriptive research frequently provides the basis for:

-

Benchmarking across properties, regions, or time periods (e.g. energy consumption per m2).

-

Identification of anomalies, trends or deviations that indicate the need for further investigation.

-

Development of data-driven indicator systems, for example for ESG reporting or sustainability controlling.

-

Preparation of follow-up studies by selecting relevant variables for explanatory or experimental research.

3.4 Explanatory Research ^ top

Seeks to clarify why a phenomenon occurs by analysing cause-effect relationships and testing verifiable hypotheses.

Explanatory research - also referred to as causal or analytical research - aims to identify relationships between variables, test hypotheses, and uncover causal links. It frequently builds upon descriptive findings and often employs quantitative methods to deliver well-founded explanations for observed phenomena. The central question is: Why is something the way it is?

Tabular Overview: Explanatory Research ^ top

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Goal | Explanation of causes, mechanisms, and relationships |

| Theoretical reference | High - theories and hypotheses are central |

| Methodology | Standardised, primarily quantitative |

| Data analysis | Statistical inference (e.g. regression, significance tests) |

| Typical methods | Experiments, cross-sectional or longitudinal studies, regression analysis |

| Challenges | Proving causality, control groups, confounding variables, validity |

Basic Principles ^ top

-

Goal: The aim is to understand which factors cause a given outcome. Explanatory research goes beyond description by identifying systematic influences and testing theoretically derived hypotheses.

-

Theoretical reference: Theories provide the foundation. Hypotheses are derived from theoretical models and tested empirically. Ideally, findings contribute to theory refinement.

-

Methodology: Explanatory research requires precise, controlled methods. Common approaches include laboratory and field experiments or large-scale quantitative designs. Internal validity - ensuring that observed effects are due to the studied variables - is essential.

-

Research interest: It seeks to clarify mechanisms of influence - e.g. does an energy management system actually reduce electricity consumption? What is the impact of user behaviour on indoor climate?

-

Typical methods: Randomised controlled trials, quasi-experiments, multivariate regression, time-series analysis, or structural equation modelling are frequently applied.

Challenges ^ top

-

Demonstrating causality: Providing empirical evidence for causal links is methodologically demanding. This requires clearly defined hypotheses, control groups, and the consideration of confounding factors.

-

External validity: What holds true in a dataset or controlled experiment may not generalise to other settings. A balance between internal and external validity is essential.

-

Operationalisation: Theoretical concepts must be translated into measurable variables using valid scales or indicators. Inaccurate operationalisation compromises reliability.

-

Data requirements: High-quality, comprehensive datasets are needed. Missing values, bias, or small samples can distort results.

Examples and Application Areas ^ top

-

Examining whether certification according to DGNB or ÖGNI correlates with significantly improved energy performance in new buildings.

-

Analysing how user behaviour (e.g. window opening, equipment use) influences heating demand in office buildings.

-

Testing whether ESG reports with high transparency scores lead to better investor feedback (e.g. using regression models with control variables).

-

Conducting experimental studies to determine if visualised CO2 traffic lights influence ventilation behaviour in shared office spaces.

-

Measuring the effectiveness of information campaigns on waste reduction in residential complexes.

Exemplary Methods ^ top

-

Experiment: Random assignment of buildings to two groups - one receives an advanced energy monitoring tool, the other does not. Compare consumption afterwards.

-

Regression analysis: Assess the influence of location, building age, and technical standard on operating costs per m2.

-

Time-series analysis: Study user satisfaction before and after introducing sustainable cleaning services.

-

Quasi-experiment: Compare two real estate locations with differing ESG strategies under otherwise similar conditions to evaluate performance impact.

Possible Applications ^ top

-

Evidence-based recommendations for sustainability, energy, or real estate strategies.

-

Assessment of the effectiveness of interventions in facility management and operations.

-

Theoretical advancements in sustainable building management.

-

Reliable decision support for policymakers, practitioners, and institutions.

3.5 Evaluative Research ^ top

Systematically assesses the effectiveness, impact, or quality of measures, programmes, or processes based on pre-defined criteria.

Evaluative research examines whether and to what extent certain interventions or programmes achieve their intended objectives. It is typically applied in practical contexts, such as project monitoring, pilot evaluations, or policy reviews. At its core lies the assessment - not merely the description or explanation. It is based on a systematic evaluation design employing qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods.

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Goal | Assessment of effectiveness, efficiency, impact or quality |

| Theory Relation | Goal-oriented, often theory-driven (e.g. logic models) |

| Methods | Mixed methods are common; context-dependent |

| Data Analysis | Depending on objectives: qualitative, quantitative or integrated |

| Typical Methods | Impact analysis, surveys, goal attainment checks, multi-criteria decision making |

| Challenges | Goal conflicts, ambiguity of criteria, attribution of effects |

Foundational Aspects & Characteristics ^ top

-

Goal: Evaluative research aims to assess, rather than merely observe, interventions or initiatives. It provides decision-makers in policy, administration, and industry with reliable information regarding the usefulness or necessary adjustments of a programme.

-

Theory relation: Evaluations often rely on an impact logic model (e.g. input - output - outcome - impact) that articulates the assumed causal mechanisms behind a measure. This model serves as the frame of reference for assessment.

-

Methods: Depending on the research question, qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods are applied. Mixed-methods designs are common as they enable the analysis of both outcomes and context-related acceptance factors.

-

Research interest: The main question is not theoretical development, but: "Does this intervention work - for whom, in which context, and at what cost?" Evaluation criteria may include effectiveness, efficiency, sustainability, or acceptance.

-

Typical methods: Stakeholder interviews, target achievement analyses, before-and-after comparisons, cost-benefit analyses, or standardised feedback systems.

Challenges ^ top

-

Goal conflicts: Different stakeholders may pursue conflicting expectations. Evaluations must manage and transparently communicate competing perspectives.

-

Unclear evaluation criteria: What exactly constitutes "success" is not always evident. Criteria must be jointly defined, plausibly operationalised, and documented transparently.

-

Attribution of effects: In complex environments, it is often difficult to clearly attribute observed effects to a specific intervention.

-

Role ambiguity: Evaluators frequently operate between research, consultancy, and control. This requires critical role reflection and ethical clarity.

Examples & Fields of Application ^ top

-

Evaluation of an energy-saving programme in schools: Were energy savings achieved? What educational outcomes were observed?

-

Assessment of the effectiveness of ESG training programmes for facility managers in large corporations.

-

Analysis of the success of a sustainable housing concept in municipal building projects (e.g. passive house standard, mobility connections, social inclusion).

-

Evaluation of user participation in office planning: Was the participatory process perceived as effective and meaningful?

-

Assessment of a CAFM system’s efficiency in technical building management in terms of time savings and data quality.

Sample Methods ^ top

-

Before-after comparison: Evaluation of energy metrics and user feedback before and after the implementation of an energy monitoring system.

-

Goal attainment analysis: Assessment of whether sustainability goals (e.g. CO2 reduction, accessibility) in a construction project were met.

-

Multi-criteria analysis: Structured evaluation of different site options for a green building project, using weighted indicators such as accessibility, cost, and environmental impact.

-

Interviews and focus groups: Qualitative assessment of perceived impacts by users, stakeholders, or project managers.

Potential Applications ^ top

-

Strategic decisions on continuation, modification, or termination of measures or programmes.

-

Accountability towards funders, public authorities, or the wider public.

-

Development of good practice models in facility management or sustainable building operation.

-

Quality enhancement and optimisation through formative evaluation during implementation.

Reflection Task / Activity ^ top

Find three academic studies in a field of your choice.

Assign each study to one of the four research types discussed in this chapter - and justify your categorisation in one to two sentences.4. Bachelor's Thesis, Master's Thesis & Doctoral Dissertation Compared ^ top

Student academic papers at universities differ not only in scope but also in their objectives and research ambitions. What they have in common is that they are based on academic methods and sources, yet with each level the requirements for theoretical depth, research competence and contribution to academic discourse increase. The following table contrasts key characteristics:

| Feature | Bachelor’s Thesis | Master’s Thesis | Doctoral Dissertation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Summarise, reflect on, and apply existing knowledge; first steps in independent analysis | Conduct independent research aiming to contribute new findings to the field | Systematic, original research with a significant contribution to scientific knowledge |

| Research Gap | Not strictly required, but may be addressed | Essential: clear distinction from existing research | Central: independent identification and addressing of a research gap |

| Methodological Competence | Use of established methods, usually basic empirical approaches | Mixed methods, advanced empirical or conceptual methods | Complex methodological systems, often involving theory-led reflection |

| Use of Literature | Systematic review of fundamental literature; introduction to scientific reasoning | Critical and indepth engagement with specialist and international literature | Comprehensive, systematic and often interdisciplinary literature review based on current research |

| Academic Standard | Scientifically sound but primarily practice-oriented | Theory-based, well-argued, academically advanced | Research-based, innovative, theoretically and epistemologically contributive |

| Evidence & Argumentation | Required: coherent and properly referenced arguments based on literature and data | Required: precise citations and methodologically validated references | Indepth source work including archival or primary sources; high standards of traceability and validity |

| Permissible Formats | No mere summaries | No purely practical formats | Independent scientific contribution |

| Publishing Requirement | Not required | Possible, except with embargo | Usually publicly available, sometimes mandatory |

| Independence | First independent research project with close supervision | Self-planned and conducted, with supervision as needed | Long-term research project with limited supervision |

5. Phases of an Academic Thesis ^ top

The path towards completing an academic thesis is rarely linear. It requires planning, methodological reflection, critical engagement with existing knowledge, and, not least, the ability to systematically structure and clearly present one's own ideas in writing. Regardless of the specific disciplinary context, the process can be divided into three interdependent and partly overlapping phases: conceptual preparation, research engagement, and editorial finalisation.

Throughout all three phases, it is essential to continuously record information, literature, methodological considerations, and personal reflections. A personal knowledge repository - for example, a research journal, a structured notebook, or a digital documentation system - not only helps trace one’s own thinking but also enables the identification and integration of links between theory, method, and findings as the work progresses.

5.1 Topic Selection & Concept Development ^ top

The process begins with the selection of a thematic focus, often motivated by personal interests, societal relevance, or research gaps identified in the academic literature. From a broad subject area, an initial problem statement should be developed to specify the research interest and determine a clear direction. Even in this early phase, literature review plays a key role. By surveying relevant sources, one can assess whether the topic is viable, identify existing theoretical and empirical approaches, and pinpoint unresolved questions or controversies. Engaging with existing studies helps situate the project within the research context, guides the choice of methodology, and sharpens one’s perspective. The goal of this phase is to develop a sound research concept, usually in the form of a proposal (exposé), which includes the following elements:

-

a preliminary yet clearly defined research question;

-

defined objectives as well as explicit non-objectives to maintain focus;

-

considerations regarding data availability, methodological approach, and potential constraints;

-

a realistic timeline and work plan, including buffer periods for unexpected delays.

5.2 Research Engagement & Execution ^ top

Once the research question has been formulated, the actual research phase begins. This second phase involves deeper engagement with the academic literature and the planning and execution of one’s own empirical investigations or analyses. The aim is to find systematic answers to the research question, drawing upon theoretical concepts, methodological expertise, and empirical data. This phase includes defining key terms, constructing theoretical frameworks, and reviewing the state of the art. These steps not only position the project within the academic discourse but also serve to justify arguments and methodological choices. Own research - whether qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods - depends on a coherent and rigorous application of methods. This includes selecting appropriate tools for data collection and analysis, reflecting on research ethics, carefully planning data collection, and addressing uncertainty, bias, or disturbances. This phase is often iterative: New insights from literature or data analysis may require adjustment of theoretical assumptions or refinement of methodological approaches. A constant alignment between theory, empirical data, and reflection is therefore crucial.

At the end of this phase, you should have:

-

a structured literature overview with systematically documented sources (ideally supported by a reference management tool);

-

your research findings, analysed, processed, and interpreted;

-

and comprehensive text modules for the chapters on background/problem, theory, methodology, and findings.

5.3 Writing & Final Editing ^ top

The third phase focuses on transforming research results and theoretical foundations into a coherent and formally correct academic text. This requires not only stylistic precision but also analytical clarity and editorial discipline.

This phase includes writing and revising all chapters - from the introduction and theoretical and methodological foundations to the presentation of results, discussion, and conclusion. Text coherence, logical argumentation, and internal consistency are key quality criteria. Earlier notes, quotations, and drafts serve as the basis for the final version.

Final editing involves linguistic and formal refinement. This includes:

-

proofreading for spelling, grammar, and style;

-

verifying all citations and references, including adherence to the required citation style;

-

consistent layout of text, figures and tables;

-

and where applicable, the preparation of an abstract, appendices, a declaration of originality, or a summary in another language.

6. Academic Writing = Career Advantage?! ^ top

Academic writing is often perceived as a formal academic requirement whose relevance to professional practice is not immediately obvious. However, this perception changes when academic writing is understood not merely as a means of generating knowledge, but as a structured form of thinking and acting that remains highly applicable beyond the university context. The competencies developed through academic writing correspond closely to key demands of the workplace - especially in knowledge-intensive, planning-oriented, or analytical professions.

The following list provides insight into cross-disciplinary skills that extend far beyond the requirements of a specific thesis. While not exhaustive, it illustrates how academic writing can serve as a foundation for structured, reflective, and professional work - whether in complex project management, concept development, market analysis, or the facilitation of change processes.

-

Decision-making under uncertainty: Academic writing involves selecting from various topics, methods, or sources despite limited information. This ability to make justified decisions and reduce uncertainty systematically is central to project-based roles in consulting, management, or development.

-

Problem awareness and focus: Developing a research question requires sustained engagement with a topic over weeks or months - even in phases of uncertainty, repetition, or frustration. Such perseverance and self-motivation are essential for managing long-term professional projects.

-

Thematic depth and perseverance: Targeted research using academic databases, bibliographies, and peer-reviewed journals fosters structured information management. It also trains the ability to distinguish relevant from irrelevant sources - a core competency in today's data-driven work environment.

-

Information literacy and research skills: Formulating a clear research question requires precise problem definition, deliberate delimitation of the topic, and critical engagement with the relevant context. This capacity for abstraction and focus is fundamental to all professional analysis.

-

Analytical text processing: The ability to quickly comprehend extensive texts, identify key points, and critically assess them is vital - not only for literature reviews but also when dealing with policies, reports, studies, or contracts in professional settings.

-

Condensation and audience-appropriate communication: Academic writing demands that complex content be articulated precisely - whether in summarising study results or citing extensive sources accurately. This skill enhances professional communication - for example, in reports, presentations, or decision-making briefs.

-