Copyright, Plagiarism & AI

Master legal & ethical principles of copyright, academic integrity, and responsible AI use in scholarly work.

Summary [made with AI]

Note: This summary was produced with AI support, then reviewed and approved.

- Copyright protects intellectual creations such as texts, images, music, software or research data. It safeguards the moral and economic interests of authors and defines who decides on use and publication.

- Intellectual property includes copyright, patent law, trademark law and design law. The key requirement is originality, meaning a personal intellectual creation with recognisable individuality. Pure functionality or automatically generated content does not meet this threshold.

- AI-generated content is only protected if humans make creative contributions, for example through selection, editing or original structuring. Prompts are usually not protected unless they are individually creative in a literary or artistic sense.

- Copyright distinguishes between moral rights (attribution, integrity of the work, first publication) and economic exploitation rights (reproduction, distribution, performance, online availability). Exploitation rights can be transferred via licences.

- Terms and Conditions of software providers are binding contracts. They regulate practical use more narrowly than copyright law and violations may lead to suspension, deletion or claims for damages.

- So-called free-to-use content carries risks because rights are often unclear. Users remain responsible for legal compliance and can be liable even if they acted in good faith. Creating your own or using clearly licensed materials is safer.

- Different types of works such as images, music or videos are subject to specific protection dimensions, including personality rights, neighbouring rights or panorama freedom. The right to one’s own image applies even in public spaces.

- Infringements can have civil law consequences (injunctions, compensation, removal) or criminal penalties. Even students may face consequences, for instance when publishing seminar papers with unauthorised images or videos.

- For education and research, exceptions such as quotations or teaching provisions exist but apply only under strict conditions such as purpose, proportionality, source attribution and non-commercial context.

- Plagiarism violates academic integrity and is considered serious both legally and institutionally. It occurs not only through verbatim copying but also through inadequate paraphrasing, missing references or structural imitation.

Topics & Content

- Reflection Task / Activity

- 1 Basics of Copyright Law

- 1.1 Intellectual Property and Copyright

- 1.1.1 Types of Works

- 1.1.2 Originality and Threshold of Creativity

- AI & Copyright

- 1.1.3 Duration and Start of Protection

- 1.2 Copyright & Usage Rights

- 1.2.1 Moral Rights of Authors

- 1.2.2 Economic (Exploitation) Rights

- 1.2.3 Transferability and Licensing

- 1.3 Terms and Conditions (AGBs) and Usage Restrictions of Software

- 1.3.1 Distinction from Copyright and Licences

- 1.3.2 Practical Examples

- 1.3.3 Relevance for Study, Teaching and Research

- 1.4 Seemingly Free-to-Use Content

- 1.4.1 Responsibility of Users

- 1.4.2 Relevance for Study, Teaching and Research

- 1.5 Special Protection Dimensions by Type of Work

- 1.5.1 Images and Visual Content

- Right to One’s Own Image

- Panorama Freedom

- Indoor Spaces

- Design Protection

- 1.5.2 Music & Sound Recordings

- 1.5.3 Videos & Audiovisual Media

- Recordings of Teaching Sessions

- 1.5 Consequences of Infringement

- 1.5.1 Civil Law Consequences

- 1.5.2 Criminal Law Consequences

- 2 Limitations, Quotations & Academic Practice

- 2.1 Legal Exceptions for Education and Research

- Checklist

- 2.2 Requirements for Quotations as Legal Exception

- 2.2.1 Short Quotations vs. Extended Quotations

- 2.2.2 Citable Sources and the Obligation to Reference

- 2.2.3 Practical Guidelines for Quotation Use

- 2.3 Plagiarism and Academic Misconduct

- 2.3.1 Plagiarism vs. Permissible Use

- 2.3.2 Consequences of Academic Misconduct

- 3 Open Licences, OER & Public Domain

- 3.1 Creative Commons

- 3.1.1 Overview of Licence Types

- Compatibility Table of CC Licences

- CC Licence Selection Tool

- 3.1.2 Mandatory Elements and Wording of Licence Notices

- Example of a complete licence notice:

- Different Wording and Placement Depending on the Medium

- Additional Metadata

- 3.1.3 Avoiding Mistakes

- Checklist

- 3.2 Open Educational Resources (OER)

- 3.2.1 OER as a Tool for Participation, Innovation and Sustainable Higher Education

- 3.2.2 Use, Adaptation and Redistribution

- 3.2.3 Distinction: Creative Commons is not the same as OER

- Only the following are OER-compliant:

- OER is more than just a licence

- 3.3 Public Domain / Gemeinfreiheit

- 3.3.1 Difference from the CC0 Licence

- 3.3.2 Possibilities for Use

- 4. Artificial Intelligence in Academic Work

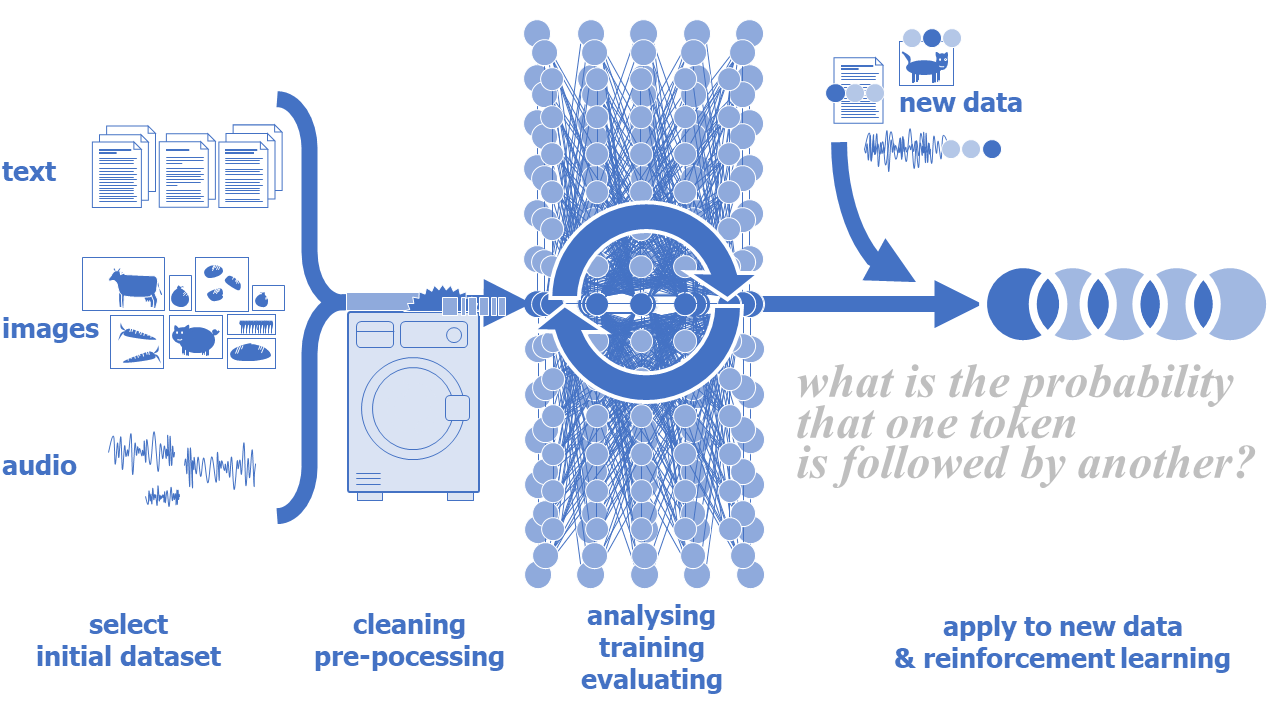

- 4.1 Foundations and Functionality of Artificial Intelligence

- 4.1.1 Terminological Clarification

- 4.1.2 Training Data and Model Architecture

- For further insights into how large language models (LLMs) work...

- 4.2 Legal Framework and Copyright in the Context of AI

- 4.2.1 OECD Principles for Trustworthy AI

- 4.2.2 EU AI Act

- Risk-Based Regulatory Approach

- Transparency Obligations for General-Purpose AI (GPAI)

- Extended Obligations for Systemically Risky GPAI

- 4.2.3 General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

- Common Data Protection Issues in the Use of Generative AI

- Recommendations for GDPR-Compliant Use of AI

- 4.2.4 Copyright and Ownership of AI-Generated Content

- 4.3.1 Potential and Opportunities

- 4.3.2 Challenges and Limitations

- 4.3.3 Scientific Standards & Disclosure Requirements

- 4.4 Effective Prompting

- 4.4.1 How Language Models Process Prompts

- 4.4.2 Examples of Effective Prompt Engineering

Reflection Task / Activity ^ top

How naturally do you use content created by others in your daily life - for example in presentations, written assignments, social media posts or research?

Reflect on three situations from your academic or professional life where you used someone else’s work (e.g. images, texts, data, videos).

Consider whether this use was legally allowed - and whether you yourself are the author of any works. Write down your examples and initial assessments.1 Basics of Copyright Law ^ top

Copyright protects intellectual creations by individuals in the form of texts, images, music, films, software, academic work and other forms of expression. It defines who holds the right to decide how a work may be used, and under what conditions third parties may use it. The purpose of copyright law is to safeguard both the moral and economic interests of creators while also balancing protection with education, research and participation in society.

In the context of academic study, teaching and research, copyright is highly relevant. Students, lecturers and researchers are both creators of original content and users of others' works. It is therefore essential to understand what counts as a protectable work, what rights creators have, how usage rights can be defined, and what legal exceptions apply to education and science.

This chapter introduces the legal foundations of copyright law and explains key concepts such as work, authorship, usage rights and exploitation rights. It clarifies what rights arise by law, when these are infringed, and what role images, music, videos and other digital content play in academic work.

1.1 Intellectual Property and Copyright ^ top

The term intellectual property refers to all legal protections for intangible goods. These include in particular:

-

copyright for creative works in the fields of art, literature and science,

-

patent law for technical inventions,

-

trademark law for product and service identifiers,

-

design law for visual and aesthetic creations.

These rights grant exclusive usage rights - even though they do not apply to tangible objects. Authors have the exclusive right to decide whether, how and by whom their work may be used. Copyright law thus protects not only economic interests but also the moral rights to the integrity and recognition of one's own work.

Copyright is a key form of protection for intellectual property in European legal systems. It protects works of literature, science and the arts - including texts, images, music, films, software and research data - from unauthorised use and grants creators the exclusive right to decide on their publication, modification and commercial use.

| Level | Legal Basis | Main Content Focus |

|---|---|---|

| EU | EU Copyright Directive 2001/29/EC | Sets minimum standards for protection scope and rights clarity in the digital EU |

| EU | Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (EU 2019/790) | Modernises copyright for online platforms; exemptions for education & research |

| Austria | Copyright Act (öUrhG) | Differentiates between moral rights, economic exploitation rights & exceptions for education/research |

| Germany | Copyright Act (UrhG-DE) | Comprehensive rules on types of works, usage rights, exceptions and criminal provisions |

1.1.1 Types of Works ^ top

Copyright protects works that qualify as original intellectual creations. Several types of works are recognised, which - depending on national legislation - are typically categorised using similar systems.

| Country | Legal Basis | Legal Definition of a Work |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | Section 1, §§1-9 öUrhG | "Works of literature, musical works, visual and cinematographic arts that are original intellectual creations." |

| Germany | §2 UrhG-DE | "Personal intellectual creations" in defined categories (e.g. literary works, musical works, photographic works, etc.) |

The following table provides an overview of typical categories of works protected under copyright law:

| Type of Work | Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Literary works | academic texts, novels, articles, blogs, emails | even short forms may be protected if they are individually crafted |

| Musical works | melodies, compositions, arrangements | especially protected when they involve original sequencing and rhythm |

| Visual arts | photographs, drawings, paintings, collages | includes digital images and installations |

| Cinematographic works | feature films, documentaries, educational videos | combine multiple types of work (sound, image, editing) |

| Computer programmes | software, apps, simulations | also includes GUI design (user interfaces) |

| Technical representations | diagrams, tables, schematics | protected only if individually designed; not for pure data reproduction |

| Applied art / design | furniture, fashion, product drafts | may overlap with design or utility model protection |

| Multimedia works | websites, infographics, digital presentations | only protected if individually designed, not if made from standard templates |

1.1.2 Originality and Threshold of Creativity ^ top

Whether a work is protected by copyright does not depend solely on its form or category. The key criterion is whether it meets the required threshold of originality - meaning it must show a sufficient level of creative input. This term is rarely defined in legal texts but has been clarified through case law and academic literature.

The central question is always: Is the work the result of a personal, creative performance?

The following aspects are essential in determining whether a work is original in the sense of copyright law:

-

Personal intellectual creation

The work must be the result of a deliberate, individual process. It is not enough if the content is generated purely by chance, mechanically, or automatically - for example by a camera in automatic mode or by AI without human editorial input. -

Creative freedom / mode of expression

There must be some degree of freedom in which the author makes personal choices - for example regarding style, language, structure, perspective, melody or composition. The greater this freedom, the more likely the work will be recognised as original. -

Threshold of creativity / individuality

The work must clearly stand out from everyday, routine or purely functional expressions. Standard phrases, templates, data compilations or procedural outputs usually do not qualify. Individuality must be expressed in the form - not just in the topic or purpose. -

Personal signature

An original work bears the recognisable "handwriting" of its creator. This may be evident in the style, language, concept or design - for instance through a creative approach, a unique composition or an innovative combination of elements. -

No purely functional character

Works whose form is determined solely by technical requirements or functional use (e.g. many forms, technical drawings, instruction manuals) are generally not considered original. Factual presentations that do not deviate from the norm in their design also fail to meet the threshold. -

Fixation in a specific form of expression

Ideas, theories, concepts or methods are not protectable - only their individual expression. For example: the thought "climate change is a challenge" is free, but a personally written article about climate policy with a unique structure and wording can be protected.

In the European legal context, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) has clarified the originality requirement. According to its consistent rulings (e.g. Infopaq, C-5/08), a work must be the result of the author’s "own intellectual creation". This definition is also decisive in Austria and Germany.

Originality is not about the subject - it’s about the form. What matters is the expression, not the topic.

Depending on the type of work, the required level of creativity may vary. For art, literature and music, a low level of individuality is often sufficient. For technical or academic representations, higher standards apply due to external constraints such as functionality, norms or purpose.

AI & Copyright ^ top

Especially in connection with artificial intelligence (AI), the following applies: content that is entirely generated by algorithms or large language models (LLMs) such as Mistral, ChatGPT, DALL·E or similar systems is not automatically protected by copyright - neither in favour of the AI (which is not a legal entity), nor in favour of the user.

An AI-generated work can only be protected by copyright if the following conditions are met:

-

A natural person makes independent decisions about the content, structure or style and uses the AI output deliberately as a starting point, raw material or source of inspiration.

-

The human user makes an original contribution through selection, arrangement, editing or combination of AI-generated material - going beyond mere automation.

-

The final product shows recognisable individual characteristics contributed by the user - for example, through stylistic refinement, creative structuring or an original interpretation of a topic.

In general, prompts - i.e. the input commands to the AI - are not protected by copyright. They are usually simple instructions or functional commands.

An exception applies only if the prompt itself already shows a creative and linguistically original design - for example as a literary instruction, poetic structure, dramatic scene or intentionally composed text:

| Prompt Example | Protected by Copyright? | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| "Create an outline on the topic of sustainable urban development." | No | Functional instruction, no individual linguistic or artistic performance |

| "Write a short story in the style of Kafka about a future where architects only work for AI housing machines …" | possible | Individually formulated text, literary style, dramatic composition, personal design |

Not everything that appears creative is protected by copyright - what counts is the original contribution of a natural person.

1.1.3 Duration and Start of Protection ^ top

Copyright protection arises automatically when a work is created - regardless of whether it is published, registered or commercially exploited. Unlike patent or trademark law, no registration is required.

The key requirement is that the work qualifies as a personal intellectual creation. Once this is met, copyright protection applies.

Protection begins as soon as the work has reached a recognisable and complete form of expression. Publication is not required. Sketches, drafts, unpublished manuscripts or digital prototypes may also be protected.

The duration of protection is largely harmonised between Austria and Germany. According to §60 öUrhG (Austria) and §64 UrhG-DE (Germany), the duration is:

- 70 years after the author’s death (post mortem auctoris),

- for joint works: 70 years after the death of the last surviving co-author,

- for anonymous or pseudonymous works: 70 years after first publication (unless the author becomes known),

- for computer programs: also 70 years after the author’s death.

After this period, the work enters the public domain. It may then be used, edited, copied and shared freely - without the permission of the original author or their legal successors.

However, even when a work becomes public domain - i.e. after the protection period expires - other legal rights may still apply. These can restrict free use or require additional permissions:

-

Right to one’s own image

In Austria, the right to one’s own image is defined in §78 öUrhG. It protects individuals from unauthorised publication or distribution of their image, especially when it violates personal rights, privacy or reputation.

In Germany, this right is governed by the Art Copyright Act (KUG), particularly §§22 and 23. Here too, images of individuals may only be published with their consent, unless a legally defined exception applies (e.g. relevance to contemporary history). -

Design and trademark rights

Even if a copyright-protected product photo or packaging enters the public domain, design or trademark protection may still apply.

In Austria, this is regulated by the Design Protection Act (MuSchG), in Germany by the Design Act (DesignG). Trademark protection is regulated by the Trademark Protection Act (MSchG) in Austria and the Trademark Act (MarkenG) in Germany. These rights apply independently of copyright and may remain valid longer - particularly for logos, product designs or characteristic packaging. -

Citation requirements in academic contexts

Even for public domain texts, images or data, academic work still requires correct citation of sources. This is not a copyright rule, but part of good academic practice.

In Austria, these standards are outlined by the OeAD and the Austrian Agency for Research Integrity (ÖAWI).

In Germany, they are defined by the DFG Guidelines for Safeguarding Good Research Practice. Anyone using external works - even public domain ones - must clearly indicate their origin.

1.2 Copyright & Usage Rights ^ top

Copyright not only provides protection but also grants specific rights that arise from the creation of a work. These rights define who may do what with a work, whether others may use it, and under what conditions. In higher education, this especially concerns the use of teaching materials, academic texts, data, images, music and videos.

1.2.1 Moral Rights of Authors ^ top

Moral rights protect the personal connection between an author and their work. These rights are inalienable and non-transferable, though they may be limited or modified by contract - for example, in employment or publishing agreements. In Austria, they are regulated in §§19ff öUrhG, and in Germany in §§12-14 UrhG-DE.

| Right | Description | § & Title (AT) | § & Title (DE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right to attribution (naming the author) | The author has the unwaivable right to be named as the creator of the work. This applies in public communications (e.g. book covers, exhibition catalogues, video credits, online publications) as well as in metadata or reuse. | §19 öUrhG - Right to be named as author | §13 UrhG-DE - Right to acknowledgement |

| Right of first publication | Only the author may decide if, when and how a work is first made publicly available. This is a core expression of intellectual freedom. | §19(2) öUrhG - Right of first publication | §12 UrhG-DE - Right to decide on publication |

| Right to integrity of the work (protection from distortion) | The author may object to any distortion or harmful alteration of their work, especially if it affects artistic expression or meaning. | §20 öUrhG - Ban on distortion | §14 UrhG-DE - Protection from distortion |

| Right to title protection | The original title of a work enjoys independent protection under Austrian law. In Germany, titles may be protected via trademark or competition law. | §21 öUrhG - Protection of work titles | §5 MarkenG or §§3,4 UWG |

| Protection from unauthorised access or seizure | Authors may prevent their work from being used, destroyed or sold without consent - even in private or state contexts. | §22 öUrhG - Protection from interference | Derivable from §14 UrhG-DE; also general civil law |

| Inalienability of moral rights | In Austria, waiving moral rights is explicitly prohibited. In Germany, it is not legally regulated but generally considered inadmissible. | §23 öUrhG - Ban on waiver | Not explicitly regulated, but inferred from legal principles |

Example: An author can prohibit their poem from being used in a political context that does not align with their beliefs - even if it is formally cited correctly.

1.2.2 Economic (Exploitation) Rights ^ top

Economic rights govern the commercial use of a work. They give the author exclusive control over how their work is used materially or digitally. In Austria, these rights are defined in §§14-18 öUrhG, and in Germany in §§15-24 UrhG-DE.

| Right | Description | § & Title (AT) | § & Title (DE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reproduction right | Covers the right to copy the work in full or in part, digitise it, film it, scan it, or reproduce it by other technical means. Applies to both analogue and digital formats. | §15(1) Z1 öUrhG | §16 UrhG-DE |

| Distribution right | Covers the right to distribute the work in physical form - e.g. by selling, renting, leasing or transferring it in other ways. | §16 öUrhG | §17 UrhG-DE |

| Exhibition right | Relates to the public display of original works - e.g. paintings, sculptures, installations or other physical objects. | §18a öUrhG | §18 UrhG-DE |

| Adaptation right (derivative works) | Covers the right to alter, develop or incorporate the work into a new one - e.g. through translation, arrangement or film adaptation. | §14 öUrhG | §23 UrhG-DE |

| Broadcasting right | Covers the right to transmit the work via radio, satellite, cable or other electronic media - especially TV, radio or livestream. | §17 öUrhG | §20 UrhG-DE |

| Public performance right | Covers the presentation of the work to an audience - e.g. in cinemas, theatres, lectures, concerts or public venues. | §18 öUrhG | §19 UrhG-DE |

| Online making-available right | Covers the right to upload the work online so that it can be accessed at a chosen time and place (e.g. YouTube, websites, podcasts, e-books, LMS). | §18a öUrhG | §19a UrhG-DE |

| Rental and lending right | Refers to time-limited use by third parties - e.g. via libraries, video rentals or software licences. | §16a öUrhG | §17(2) UrhG-DE |

| Display right for works on built property | Covers buildings or artworks placed permanently in public spaces - such as buildings, sculptures or façade art. | §16(3) öUrhG | §59 UrhG-DE ("panorama freedom") |

Example: A lecturer uploading a self-produced video to YouTube exercises their right to make the work publicly available - provided they are the original creator of the video.

1.2.3 Transferability and Licensing ^ top

While moral rights are fundamentally non-transferable, exploitation rights can be transferred in whole or in part, or granted to others via licensing agreements. The following types of licences are common:

| Type of Rights Transfer | Description |

|---|---|

| Simple licence | The licensee may use the work alongside others - the author may grant additional licences to others. |

| Exclusive licence | Only the licensee may use the work - the author waives their own usage rights. |

| Time-limited | Rights are granted for a specific period only. |

| Territory-limited | Usage is restricted to certain countries or regions. |

| Scope-limited | The licence applies only to specific types of use (e.g. print only, e-learning only). |

Note: Licensing agreements should always be recorded in writing and formulated as clearly as possible - especially for projects involving multiple contributors or intended for publication.

1.3 Terms and Conditions (AGBs) and Usage Restrictions of Software ^ top

Terms and Conditions (AGBs) are standardised contractual provisions pre-formulated by companies for a wide range of agreements. Users generally accept these terms either by clicking a confirmation box ("I agree") or implicitly through the use of a service. From a legal perspective, they are not merely guidance but binding contractual components.

This means: Anyone using a programme or platform enters into a civil law contract with the provider. Even if no individual contract has been negotiated, the AGBs apply in full - as long as they do not conflict with mandatory law. A breach of AGBs is therefore not a typical copyright infringement, but it can be a violation of contract with serious consequences (e.g. account suspension, compensation claims, formal warnings).

1.3.1 Distinction from Copyright and Licences ^ top

-

Copyright: Arises automatically with the creation of a work and protects the rights of the author.

-

Licence agreement: Grants third parties the right to use specific copyright-protected content.

-

Terms and Conditions (AGBs): Define how and where such content or software may be used. They may restrict usage more narrowly than copyright law itself.

Thus, AGBs extend the legal framework: they do not affect the duration of copyright protection but regulate the practical use of software, templates or design elements.

1.3.2 Practical Examples ^ top

-

According to Canva's Content License Agreement (Chapter 9, Paragraph 10), it is prohibited to use Canva content in any product that allows for the redistribution or reuse of the content in a way that enables extraction, access, or reproduction as an electronic file. This is particularly relevant when creating PDFs, as the nature of this format makes it extremely difficult to prevent the extraction of embedded Canva content such as themes, graphics, or images. Since PDF files can be easily edited and elements can be extracted or reused, incorporating Canva content in PDFs would violate the licensing agreement. As the creator, you are responsible for ensuring that Canva’s licensing terms are followed and are liable for any claims arising from improper use of licensed content.

-

Using Microsoft Premium Creative Content in PDFs can present challenges due to the licensing restrictions outlined in Microsoft’s terms. While it is permissible to embed these graphics, themes, and icons in documents created with Microsoft 365 and export them to formats like PDF, the extraction or reuse of such content outside of Microsoft applications is prohibited. PDFs, by nature, often allow for the extraction of embedded elements, which may violate these licensing rules. Even with security settings, such as restricting editing or copying, there is no absolute guarantee against unauthorised extraction. As a creator you should be aware of these risks and ensure compliance with Microsoft’s licensing agreements to avoid potential liability.

1.3.3 Relevance for Study, Teaching and Research ^ top

The importance of AGBs is particularly evident in the academic context. Anyone working with digital tools, templates or stock materials in study or research does not act solely within the scope of copyright, but also within a contractual framework defined by the providers.

A breach of AGBs is not a classic copyright infringement but a violation of the user contract with the provider. The consequences can be significant: providers such as Canva or Microsoft reserve the right in their AGBs to suspend accounts without notice, delete content, or even take legal action for damages. This also applies to content created in the context of study programmes.

In lectures, academic publications, presentations or university projects the question often arises whether the use of specific templates or design elements is permissible. Many AGBs are deliberately broad and allow room for interpretation. For instance, it may be acceptable to show a Canva graphic in a university presentation, but not to redistribute the same graphic as an openly accessible PDF, since the design elements could be extracted. Similarly, Microsoft design templates are often subject to restrictive conditions that allow redistribution only within the Microsoft environment.

This issue becomes particularly critical in university projects involving external partners or companies: in such cases, the copyright exceptions for teaching and research do not apply. The unauthorised redistribution of files from which design elements could be extracted constitutes a clear breach of contract. Special caution is therefore required in collaborative projects.

To avoid legal uncertainty, it is advisable to create and use your own graphics and design elements or rely on content that is clearly licensed for the intended purpose.

1.4 Seemingly Free-to-Use Content ^ top

The internet hosts countless platforms offering images, music, videos or graphics as "free to use" or "royalty-free". At first glance, such content appears to be a simple and convenient solution, particularly for students, lecturers and researchers who need visual or multimedia material quickly. However, behind this apparent freedom lie significant legal risks. It cannot always be guaranteed that the works in question were genuinely released by their original authors, or that the stated licence is in fact valid.

1.4.1 Responsibility of Users ^ top

Many open platforms that provide content under CC0 or similar licences rely on user uploads. The difficulty is that there is often no verification of rights. A person can upload a photo, illustration or piece of music to which they hold no rights. If such a work is incorrectly labelled as "public domain", users may gain a false sense of security.

Another risk is the lack of reliable documentation. Most platforms do not require registration, nor do they provide a binding confirmation of who uploaded or downloaded the content. This means there is no firm evidence that the work was genuinely published with the consent of the authors and downloaded under the conditions stated.

Particularly problematic is the possibility of retrospective claims. Even if an image or graphic was originally available under CC0 or in the public domain, it may later be re-licensed, a rights holder may discover unauthorised use, or fraudulent parties may attempt to demand fees after the fact.

In all these cases, users who have already employed the material in assignments or projects may face licence claims or lawsuits for damages.

Legally, the responsibility for lawful use lies primarily with the users. Anyone who incorporates seemingly free-to-use graphics into a dissertation, publication or research project may ultimately be liable for infringements - even if the error originated with the platform or the uploader. Rights holders can demand cessation, damages or licensing fees, regardless of whether the use was in "good faith".

1.4.2 Relevance for Study, Teaching and Research ^ top

In the academic context, the uncritical use of such content can lead to serious issues. In academic writing, breaches of good research practice may occur if materials are used whose origin is unclear. In university projects involving external partners or companies, the copyright exceptions for teaching and research do not apply. Contractual breaches or licence infringements are particularly serious here, as they usually involve commercial use, where licensing costs or claims for damages may be especially high.

When in doubt, create your own content. For sensitive projects or publications this is the safest approach. If there is any uncertainty about the origin or licence of material, it is better not to use it.

1.5 Special Protection Dimensions by Type of Work ^ top

Not all works are treated equally under copyright law. Depending on the medium - such as images, music or video - specific protection dimensions, additional rights and varying legal requirements apply. These are not limited to copyright but may also include neighbouring rights such as design protection, image rights or performance rights. Anyone creating or using visual, musical or audiovisual content should carefully assess which rights are involved and what permissions are required.

The following subsections offer a structured overview of additional legal aspects that arise from the type of work - regardless of whether copyright protection applies in the strict sense.

1.5.1 Images and Visual Content ^ top

Visual works - such as photographs, illustrations, drawings, graphics, design objects and similar representations - are protected by copyright if they are personal intellectual creations. In addition, other rights often need to be considered:

-

An image is protected by copyright if it is individually crafted - through composition, lighting, choice of subject or post-processing.

-

Digital collages, scientific visualisations or creative diagrams may also qualify as protected works under copyright law.

-

Simple "snapshots" or automatically generated recordings without creative input (e.g. surveillance cameras) typically do not meet the threshold - unless performance rights apply (i.e. protection for persons or companies who significantly contribute to the exploitation of a work without being the original author - such as producers, broadcasters, performers or press publishers).

Right to One’s Own Image ^ top

Anyone who photographs or films a person infringes their personal rights. In Austria (§78 öUrhG) and Germany (§22 KUG), portraits may only be published with the consent of the person depicted.

Exceptions apply if the image is relevant to public life (e.g. at public events or of public figures), provided no legitimate interests are violated.

Extra care is needed with group photos, event recordings or scenes in public spaces. Publication is not automatically allowed just because the image was taken in a public area. What matters is whether the individual is clearly recognisable - and whether their legitimate interests could be affected.

Unproblematic are incidental images: If people appear unintentionally and only in the background, with no specific focus, this is called "incidental presence". This applies, for example, if tourists appear in the background of an architecture photo or passers-by are blurred in a street scene. In such cases, the public interest in the overall scene often outweighs personal rights.

However, explicit consent is required when:

-

a single person is clearly highlighted and portrayed as the main subject (e.g. through framing, sharpness or pose),

-

group photos are taken in private or semi-public contexts (e.g. at seminars, workshops, study groups),

-

personal data is provided, such as names, context information or geotagged metadata,

-

the image reveals behaviour, emotions, political or religious views,

-

the publication is commercial or intended for public visibility (e.g. on a university website, in social media or marketing brochures).

Particular caution is required in cases of vulnerability (e.g. children, people with disabilities, marginalised groups) and sensitive settings (e.g. during exams, in medical care, at demonstrations or in religious spaces). In these situations, publication is only lawful and ethically acceptable with informed and documented consent.

Merely being in a public space does not void the right to privacy. Even in streets, squares and lecture halls, everyone has the right not to be depicted and published against their will if personal rights are affected.

Panorama Freedom ^ top

So-called panorama freedom allows the photographing or filming and publication of works that are permanently located in public spaces - such as buildings, monuments or public artworks - without the consent of the creator or property owner.

However, this rule is not universal and varies by country. In Austria (§4(1) Z5 öUrhG) and Germany (§59 UrhG-DE), panorama freedom generally applies if:

-

the work is permanently situated in a public space (e.g. buildings, streets, parks),

-

the image is taken from a publicly accessible spot (not from drones, balconies, interiors or elevated positions with special equipment),

-

the work is not altered or portrayed in a distorting way (e.g. by offensive edits, ironic distortion or questionable contexts).

Panorama freedom is not granted everywhere - many countries lack such legislation or allow only limited use:

In France or Italy, for example, the Eiffel Tower at night or the Colosseum may not be published without permission, particularly if protected light installations, perspectives or settings are involved.

In Spain, the legal situation is unclear, meaning commercial use of photos of public buildings can be legally risky.

The same applies in the USA, Japan and Canada - especially for public artworks, logos or distinct architectural designs.

In Switzerland (§27 URG) and Liechtenstein (Art.16 LUG), a restricted form of panorama freedom exists - but it does not explicitly permit commercial use.

Many buildings in other countries serve military purposes (not always recognisable at first sight). Photographing them may be strictly prohibited.

For study abroad, field trips, research projects or social media posts, it is crucial to understand that panorama freedom is not an internationally guaranteed right. Publishing photos of buildings, artworks or installations from another country may - depending on local law - violate copyright or property rights.

Always check the legal situation before taking or sharing photos from abroad.

Indoor Spaces ^ top

Panorama freedom only applies to works in outdoor public spaces - not to those located inside buildings. As soon as an artwork, installation or architectural object is located indoors, its use generally requires permission under copyright law.

Even if entry is free or paid, these spaces are not considered public in a legal sense, but rather privately or institutionally controlled environments. The rights holders (e.g. museums, venue operators, owners) may impose conditions for photos and videos, particularly for:

- commercial use (e.g. in publications, on websites, for merchandise)

- publication in media or social platforms

- recording of tours, performances or events

Recordings used for teaching, projects or presentations are also subject to copyright law and the house rules of each institution. Just being present or holding a ticket does not entitle you to use or publish images freely.

Always check before filming or photographing indoors - and ask whether usage permission is needed. Written consent is advisable in unclear cases.

Design Protection ^ top

A visual work can, in addition to copyright, also fall under design law (in Germany: registered design, formerly known as "Geschmacksmuster"). Design protection does not cover the content or function of a work but only its external appearance - regardless of whether the design is also protected by copyright.

Design protection does not arise automatically. It must be applied for at the relevant patent office (Austrian Patent Office or German Patent and Trade Mark Office). The requirements are novelty and what is known as "individual character" - a distinctive visual appearance that differentiates the design from existing ones.

Particular attention is needed when dealing with logos, trademarks and designs that are visible in photos - for example, a bottle label on a table, a passer-by wearing a branded T-shirt, or a distinctive design object in the background of an architectural image.

If the logo or design appears only incidentally - not as the central focus of the image - this is usually not considered unlawful.

However, if a design is deliberately emphasised, highlighted or used commercially, this can infringe design or trademark rights - especially if it gives the impression that the featured product or brand is being endorsed or is part of the content.

Where possible, use neutral backgrounds or crop images to avoid showing third-party designs.

1.5.2 Music & Sound Recordings ^ top

Musical works and sound recordings are protected by multiple legal layers that go beyond classic copyright. In addition to the composition and lyrics (protected as literary and musical works), the performance, the recording itself, and the public use of the recording may all be subject to separate rights. The most relevant rights include:

-

Copyright in musical works

The composer of a musical piece is the legal author under copyright law. Protection covers melody, harmony, rhythm and structure - and possibly also song lyrics, which count as literary works.

Even a low level of creative input may be sufficient for protection. Copying short sequences of notes or rhythms can already infringe copyright if they are considered distinctive. -

Performance rights for performers

Performers - such as singers, musicians, or voice actors - are protected by neighbouring rights (§§66-71 öUrhG / §§73-75 UrhG-DE), even if they are not the original authors. This protection applies even when the performed work itself is in the public domain.

Example: An orchestra's interpretation of a classical piece is protected independently of the original composition’s copyright status. -

Protection of the sound recording ("phonogram")

The so-called phonogram producer’s right (§76 UrhG-DE / §70 öUrhG) protects the technical recording of a performance. Whoever produces the recording - such as a record label or studio - holds exclusive rights to reproduce, distribute and publicly play the recording. -

Public use and exploitation

For public performance (e.g. in lectures, videos or podcasts), a licence is usually required. This applies to the composition, the performance (e.g. singing), and the recording.

Legal exceptions for education may apply, but not for all types of use.

| Context | Typical Example | Potentially Commercial? | Rights Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presentation with background music | Image slideshow, event opener | Yes (e.g. sponsorship, public appearance) | Composition, performance, recording |

| Educational video / screencast | eLearning content with music intro | Yes (YouTube, Moodle) | Composition, performance, recording |

| Podcast / interview | Degree programme podcast with jingle | Yes (e.g. on Spotify) | Composition, performance, recording |

| Social media clip | Project teaser on Instagram | Yes | Composition, performance, recording |

| Event recording | Footage containing music segments | Yes (if published) | Composition, performance, recording |

Only use music for which you have verified the necessary usage rights for commercial or educational publication (purchased and/or under a clear licence).

1.5.3 Videos & Audiovisual Media ^ top

Videos and audiovisual content typically combine multiple protected work types into one medium. This makes their legal assessment complex: in addition to copyright for visual and audio elements, other rights may apply - including personality rights, neighbouring rights, design and trademark rights, and licensing agreements.

A video may involve the following layers of protection:

-

copyright-protected works (e.g. cinematography, editing, script, music, graphics),

-

protected performances (acting, presenting, performing),

-

protected recordings (sound/image carrier rights held by producers),

-

personality rights of individuals shown,

-

visible design or trademark rights (e.g. logos, branded packaging),

-

platform-specific legal terms (e.g. YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Spotify).

As such, videos typically involve a combination of rights that exist simultaneously. For example, an educational video may:

- be protected as an audiovisual work under copyright law,

- include music licensed through GEMA, AKM or SUISA,

- feature speakers protected under performance rights,

- show individuals who must consent to publication.

Each relevant right must be clarified - especially before publishing, performing publicly, or using commercially.

Many platforms (e.g. YouTube, Vimeo, TikTok, Instagram) require users to agree to broad licensing terms when uploading content. These often include:

-

The platform is granted permission to distribute, edit and reuse the video.

-

While authors retain copyright, they effectively give up some control over how the video is used.

Recordings of Teaching Sessions ^ top

The legality of recording teaching sessions depends on multiple factors:

-

Consent of all parties involved (especially those visible or audible in the recording),

-

Intended use: internal (e.g. on Moodle) vs. external (e.g. YouTube),

-

Use of protected content (e.g. slides, images, videos, music).

Not every self-recorded video can be published freely - copyright, personality rights and licensing issues must always be considered together.

1.5 Consequences of Infringement ^ top

In academia, intellectual property is not just a resource - it is a legal asset. Anyone using third-party content must follow the legal rules, whether through licences, legal exceptions (limitations), or correct citation. Violating copyright law can lead to serious consequences.

1.5.1 Civil Law Consequences ^ top

Authors can assert civil claims if their rights are violated:

-

Cease and desist: The use and distribution of the work must be stopped.

-

Removal: Published content must be taken down or withdrawn.

-

Damages: Compensation may be claimed, including licensing fees and further payments for lost commercial opportunities - sometimes substantial.

-

Disclosure: Users may be required to reveal how, when and where the work was used.

Even students can face civil consequences - for example, if they publish seminar papers, photos or videos containing protected material on public platforms or social media without authorisation.

1.5.2 Criminal Law Consequences ^ top

Copyright violations can be prosecuted as criminal offences in Austria and Germany, especially when committed intentionally and for commercial gain. (§§91-92 öUrhG / §§106-108a UrhG-DE)

Penalties range from fines to imprisonment of up to two years - and in serious cases, up to five years.

Repeated or deliberate use of protected content without rights clearance can also be considered intentional - especially when warnings or notices are ignored.

2 Limitations, Quotations & Academic Practice ^ top

The legal limitations to copyright (also called "exceptions") ensure that education, science and research are not disproportionately restricted by copyright law. They provide a legal basis for using certain types of works without needing explicit permission from the rights holders - for example for analysis, criticism, discussion or teaching purposes.

However, these limitations are not unlimited. They only apply when very specific conditions are met - only then is the use considered lawful.

2.1 Legal Exceptions for Education and Research ^ top

Limitations are designed to support access to knowledge and the use of third-party works in academic contexts - for analysis, critical discussion and engagement with socially relevant content. This includes quotations, copies or digital teaching materials.

However, these exceptions are not "free passes." They only apply when all of the following conditions are fulfilled:

-

Purpose requirement

The use must serve an explicitly permitted purpose - such as teaching, academic work or educational development. Purely private or commercial use is excluded. -

Proportionality

Only the necessary part of a work may be used. Full reproduction is not allowed - except in clearly justified cases (e.g. large-scale quotation in academic work). The material must be integrated with a clear educational purpose. -

Attribution

The author, title, year of publication and (if applicable) editor and publisher must be correctly cited. In Germany, this is required under §63 UrhG-DE; in Austria, under §57 öUrhG. -

Non-commercial use in a restricted context

The use must be non-commercial and take place within a closed institutional setting - e.g. a password-protected Moodle course, a lecture or a closed study group. -

No purely decorative use (no "incidental" content)

The work must not be used solely for visual enhancement. It must be directly relevant to the teaching or research context - for example, as the subject of analysis, debate or interpretation. -

Respect for the ban on modification

Works may not be altered - even if the use is allowed under a limitation. Only technical adjustments are permitted (e.g. resizing or file conversion) - and only if they do not change the nature of the work. This is regulated in §62 UrhG-DE and §14 öUrhG.

EU-wide, these limitations must follow the "three-step test" defined in Article 9(2) of the Berne Convention:

-

Use is allowed only in certain special cases,

-

It must not interfere with the normal economic use of the work,

-

It must not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author.

The Directive (EU) 2019/790 on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (CDSM) obliges all EU member states to harmonise exceptions and limitations for digital education. Key points include:

-

the country-of-origin principle (the law of the country where the provider is based applies),

-

the requirement for secure digital learning environments (e.g. Moodle rather than public YouTube),

-

and exemption from needing licences if no equivalent commercial offer exists.

| Country | Legal Basis | Specific Rule |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | §42g öUrhG | Limitation for teaching, education and research; non-commercial; source citation; only necessary portions allowed |

| Germany | §§60a-60h UrhG-DE | Comprehensive education exceptions (UrhWisG); e.g. 15% of a work, full articles, text and data mining; some uses require payment |

Checklist ^ top

These limitations provide legally secure ways to use content - but always under strict conditions. Before using third-party material, ask yourself:

Even when something is freely accessible online: that does not mean it can be used without restriction.

2.2 Requirements for Quotations as Legal Exception ^ top

Quotations are a legally permitted form of copyright exception - but only if they meet the specific requirements of copyright law. This so-called "freedom to quote" supports scholarly discourse, critical engagement with published ideas and the integration of one's own arguments into the broader research context.

2.2.1 Short Quotations vs. Extended Quotations ^ top

The legal basis for quoting in education and research is defined by national copyright limitations. In Austria (§42f öUrhG) and Germany (§51 UrhG-DE), a distinction is made between short quotations and extended (or large-scale) quotations:

| Type of Quotation | Feature & Purpose | Scope | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short quotation | Quoting individual passages for clarification, criticism or referencing | A brief excerpt of a text, image detail or music clip | Analysing a sentence from a textbook, including a short graphic in an academic talk |

| Extended quotation | Reproducing entire works or significant parts if the quoting text engages with it in depth | Complete texts or works in justified cases | Discussing an entire poem, analysing a complete research poster, reproducing full images |

Extended quotations are only allowed in exceptional, well-justified cases!

2.2.2 Citable Sources and the Obligation to Reference ^ top

Not every text or source is automatically suitable for citation. Quotations are only permitted if both the source and the quotation meet the following requirements:

-

Public availability (this also applies to sources behind paywalls, as they are generally accessible once a licence fee is paid)

-

Recognisable purpose for quoting (e.g. evidence, analysis, critique)

-

Integrated and commented on in context (not just a collection, not "decorative" or added merely as filler or eye-catcher without meaningful integration into the line of argument)

-

Formally marked and clearly referenced so the original source can be reliably identified

-

Limited to the minimum content necessary

2.2.3 Practical Guidelines for Quotation Use ^ top

Quotations are used to support arguments in academic writing - not simply to repeat what others have said. What matters is the targeted, careful and traceable use of external content within your own line of thought.

Using reference management tools (e.g. Zotero, Citavi) helps ensure correct formatting, consistency in citation style, and efficient management of large numbers of sources.

2.3 Plagiarism and Academic Misconduct ^ top

Plagiarism is considered a serious violation of academic integrity. It undermines the credibility of scholarly work, infringes the rights of original authors, and may lead to legal and institutional consequences. Plagiarism is not only a breach of examination regulations but often also a violation of copyright law.

2.3.1 Plagiarism vs. Permissible Use ^ top

Not every use of external content automatically constitutes plagiarism. What matters is the correct referencing of the source, the clear separation between your own work and third-party content, and the academic purpose of its use. The use of third-party content is only permissible if all of the following conditions are fulfilled:

-

Academic purpose

-

Full and correct citation of the source

-

Clear distinction between own work and external content

If even one of these conditions is missing, the accusation of plagiarism may be justified - even if a formal citation is present (e.g. in cases of "hidden" plagiarism).

Plagiarism can occur in many forms - not only through direct copying, but also through paraphrasing, translations, or structural imitation. The following table presents common mistakes alongside improved, citable alternatives. The examples include extracts from original sources referenced in footnotes [^Plagiat OriginalSource1] 1 2 3

| Plagiarism Type | Description | Plagiarism Example | Improved Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verbatim copy or translation without source | Original text is copied word-for-word or translated without quotation marks or indication that it is a self-made translation. | The term user satisfaction is very broad (Huber et al., 2014). In the studies of office buildings, temperature had a strong influence on user satisfaction. The term user satisfaction is defined broadly in the literature and varies by building type. |

User satisfaction is an umbrella term for various aspects in buildings (Huber et al., 2014, p.2). "In the studies of office buildings, temperature had a strong influence on user satisfaction" (Huber et al., 2014, p.8, own translation). "Der Begriff Nutzerzufriedenheit ist in der Literatur sehr weitläufig definiert und ist für die Gebäudetypologien unterschiedlich" (Busko et al., 2014, p.8). |

| Verbatim Translation Plagiarism | A foreign-language quote is translated but used without labelling it as an own translation - even if the source is correctly cited, this violates APA rules. | "Temperature had a strong influence on user satisfaction" (Huber et al., 2014, p.8). | "Temperature had a strong influence on user satisfaction" (Huber et al., 2014, p.8, own translation). |

| Paraphrase without Source | Content is taken over in meaning but no source is mentioned. | The influence factors are not clearly defined in the different studies. | According to Huber et al. (2014), no clear explanatory variables for user satisfaction can be derived from the studies (p.10). |

| Paraphrase too Close to the Original | The wording is only slightly changed and too close to the original - lacks sufficient own contribution. | The term user satisfaction is very broad and refers to different aspects in buildings (Huber et al., 2014, p.2). | Huber et al. (2014) use the term user satisfaction as an umbrella term for various usage-related aspects in buildings (p.2). |

| Wrong Source Attribution | Content is attributed to a wrong or uninvolved source. | There are no standardised questionnaires (Muhammad et al., 2013). | Huber et al. (2014) state that there is no standardised questionnaire design for measuring user satisfaction (p.10). |

| Context Plagiarism / Missing Separation | Own and external parts of text are mixed in such a way that it is not clear where the source begins or ends - despite correct attribution. | Different building types have specific requirements regarding indoor climate, which directly affects the design of user-friendly environments. This is particularly true for the perception of temperature, which has a consistent strong influence on user satisfaction in office buildings, while this connection is less studied in residential buildings - although it also shows a high impact there (Huber et al., 2014, p.8). | Different building types have specific requirements for indoor climate. Huber et al. (2014) show in their comparative analysis that the perception of temperature in office buildings has a consistently strong influence on user satisfaction, while this effect is less frequently proven in residential buildings - but still shows a clear impact (p.8). |

| Concealed Plagiarism | External content is incorporated into one's own text in such a way that it is not recognisable as such - e.g. through incomplete, unclear or deliberately misleading source attributions. | • Temperature has a strong influence on satisfaction in offices. • Updating questionnaires is absolutely necessary (own wording, but content from Huber et al., 2014). • The following aspects are derived from different sources. (No citations provided, direct and indirect usage) |

Huber et al. (2014) show that temperature in office buildings has a consistently strong impact on user satisfaction (p.8). They also point out that the data collection tools used are not standardised and need to be updated (p.10). |

| Patchwork / Mosaic Plagiarism | Content from several passages or sources is combined, with only general or incomplete source attribution. | In recent years, interest in user satisfaction has increased significantly. Differences between building types are particularly noticeable regarding the relevance of temperature as a factor. Also, the inconsistency of questionnaires and target groups is striking (Huber et al., 2014). | Huber et al. (2014) document a rise in research interest in user satisfaction (p.2) and discuss the various survey tools and their inconsistency (p.10). They also show that temperature is a strong factor for satisfaction in offices, whereas the effect is only partially confirmed in housing (p.8). |

| Adoption of Ideas | An original insight, interpretation or systematisation is used without attributing the intellectual work of another person - even if a source is mentioned. | User satisfaction varies by building type, since different factors are relevant for office and residential spaces (Huber et al., 2014). | The following reflection is based on the analysis by Huber et al. (2014, p.9), who show that user satisfaction cannot be measured in general terms, but depends significantly on the building type - e.g. due to different expectations in office vs. residential buildings. |

| Secondary Citation without Disclosure | A citation is used from a source that itself cited it - but the fact that it is a secondary source is not disclosed. | Perez et al. (2001) examine residential satisfaction of elderly people. | Perez et al. focus on the satisfaction of elderly people in housing (cited in Huber et al., 2014, p.2). |

| Structural Plagiarism | The structure, logic of argumentation or outline is copied without attributing this intellectual performance. | The following points summarise key findings on user satisfaction in buildings (Huber et al., 2014, p.10):

|

The following presentation is structurally based on the systematic outline by Huber et al. (2014, p.10):

|

Note: Even paraphrased ideas, copied structures or content-based similarities without proper source citation are considered plagiarism. The original source must always be clearly referenced and correctly cited - this also applies to translations, paraphrases or secondary citations.

2.3.2 Consequences of Academic Misconduct ^ top

Plagiarism usually leads to multi-level consequences, which may affect three main areas:

-

Academic examination regulations

- Invalidation of an assessment or exam result

- Exclusion from retake opportunities

- Dismissal from the study programme

- Withdrawal of academic degrees

-

Legal implications

- Civil claims for injunction or compensation

- Criminal prosecution for copyright violations

- Loss of reputation with long-term effects on professional careers

Academic misconduct is not a minor offence - it can permanently damage one’s career, credibility, and academic integrity.

3 Open Licences, OER & Public Domain ^ top

Open licences allow for the legal, simple and free use of copyright-protected content - especially in education, science and research. They provide a clear framework for how materials may be reused, adapted and shared - and thus strengthen the culture of sharing.

In higher education in particular, open licence models offer new opportunities: teaching materials can be more easily adapted, integrated into learning platforms or used for international cooperation. At the same time, they promote transparency, participation and the development of open educational resources (OER).

To enable lecturers, students and research teams to work legally with open content, a sound understanding of the different types of licences is necessary - as well as knowledge of their compatibility, areas of application and correct citation.

The following subsections explain open licence models (here: Creative Commons), the didactic and legal framework of OER, and the status of works in the public domain in more detail.

3.1 Creative Commons ^ top

Creative Commons was founded in the early 2000s in the USA to offer a legal alternative to traditional copyright. The initiative came from the observation that existing copyright regulations were increasingly hindering the open exchange of knowledge, education and creativity in the digital space. The aim was to develop a flexible licensing system that allows authors to release certain usage rights - without losing full control over their work.

The non-profit organisation Creative Commons was officially launched in 2001. Key founding figures included the legal scholar Lawrence Lessig, who had been dealing with digital culture and its legal regulation since the 1990s. The first version of the licences was published in 2002. It was based on the idea that specific rights - such as adaptation, reproduction or commercial use - can be released under clear conditions.

Over the years, Creative Commons developed into a global project, supported by national partner organisations in many countries. In the German-speaking world, academic institutions in Berlin and Zurich took on the localisation and legal evaluation. The original country-specific versions were later replaced by the international licence version 4.0, which has been in effect since 2013 and is available in more than 40 languages.

Today, Creative Commons is a key tool in the Open Access movement, Open Educational Resources (OER), Open Science and the free culture community. The licences are used by millions of creators worldwide - from individuals to large institutions such as Wikipedia, Flickr, universities of applied sciences and universities, museums, government agencies or publishers.

In the education sector in particular, these licences have proven to be a reliable legal means to make content freely accessible while keeping authors’ rights transparent. Creative Commons also provides supporting tools such as licence generators, informational materials, and metadata formats for digital repositories.

Based on: Creative Commons © 2025 by Wikipedia contributors, edited and summarised by Christian H. Huber (2025).

APA reference: Wikipedia contributors. (2025, August 1). Creative Commons. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Creative_Commons&oldid=1303694967. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

3.1.1 Overview of Licence Types ^ top

CC licences are made up of modular elements that can be combined.

| Abbreviation | Description | Licensing Right | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| BY | Attribution | The work may only be used if the author is properly credited. This applies to all forms of use: copying, redistribution, adaptation, and commercial use. The exact form of credit can be specified by the author. | Standard module of every CC license; recommended for OER, Open Access publications due to transparency and compatibility. |

| NC | Non-Commercial | The work may only be used for non-commercial purposes. This includes, for example, use in free educational offerings. Use in paid online courses or ad-supported platforms can be considered commercial. The distinction is not always clear. | Suitable for content meant to be openly accessible but not exploited commercially (e.g. research projects, educational initiatives, NGOs). |

| ND | No Derivatives | The work may only be redistributed in its unchanged, original form. No translations, cuts, or redesigns are allowed. This also applies to technically necessary conversions (e.g. format requirements). | Only suitable when the content's integrity must be maintained (e.g. legal texts, declarations, official documents). Not OER-compatible. |

| SA | Share Alike | Anyone who adapts the work or builds on it must publish the new work under the same license. This prevents open material from being incorporated in closed systems. | Common in open ecosystems (e.g. Wikipedia, open source), useful for OER to ensure open distribution. |

These elements are combined into six standardised licence types used globally:

-

CC BY = Attribution

This licence permits the freest use. Users may copy, distribute, make publicly accessible, adapt and use the work commercially, as long as the author is properly credited. -

CC BY-SA = Attribution, Share Alike

This licence builds on CC BY but requires that derivative works be shared under the same licence. If the material is changed or incorporated into a new work, that work must also be published as CC BY-SA. -

CC BY-NC = Attribution, Non-Commercial

The work may be used, distributed and adapted, but not for commercial purposes. Non-commercial use includes, for example, public education institutions, but potentially excludes advertising revenue, paid courses or commercial platforms. -

CC BY-ND = Attribution, No Derivatives

This licence allows use and distribution only in unchanged original form - including commercial use. Adaptations (e.g. translations, abridgements, graphic modifications) are not permitted. -

CC BY-NC-SA = Attribution, Non-Commercial, Share Alike

This licence combines the restrictions "non-commercial" and "share alike". Adaptations are allowed but must also be shared under CC BY-NC-SA and not used commercially. -

CC BY-NC-ND = Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivatives

The most restrictive CC licence: The work may only be used in its original form and for non-commercial purposes. No adaptations, no translations, no modifications allowed. -

CC0 = Public Domain Dedication

In this special form, the author voluntarily waives all rights - as far as legally possible. It is equivalent to public domain but is a conscious act of release.

Compatibility Table of CC Licences ^ top

| License Origin ↓ New Work → |

CC BY | CC BY-SA | CC BY-ND | CC BY-NC | CC BY-NC-SA | CC BY-NC-ND |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC BY | ✔ allowed | ✔ allowed | ✔ allowed | ✔ allowed | ✔ allowed | ✔ allowed |

| CC BY-SA | ✖ not allowed | ✔ allowed | ✖ not allowed | ✖ not allowed | ✖ not allowed | ✖ not allowed |

| CC BY-ND | ✖ not allowed | ✖ not allowed | ✔ allowed but no editing | ✖ not allowed | ✖ not allowed | ✔ allowed but no editing |

| CC BY-NC | ✖ not allowed | ✖ not allowed | ✖ not allowed | ✔ allowed | ✔ allowed | ✔ allowed |

| CC BY-NC-SA | ✖ not allowed | ✖ not allowed | ✖ not allowed | ✖ not allowed | ✔ allowed | ✖ not allowed |

| CC BY-NC-ND | ✖ not allowed | ✖ not allowed | ✖ not allowed | ✖ not allowed | ✖ not allowed | ✔ allowed but no editing |

The choice of a suitable Creative Commons licence depends on how openly a work should be used, adapted, and shared. To support this decision, the tool below offers a simple selection aid.

CC Licence Selection Tool ^ top

Based on two or three questions - about commercial use, permission for edits, and licence requirements for derivative works - this form identifies which of the six standard CC licence types (CC BY to CC BY-NC-ND) best matches the desired conditions.

3.1.2 Mandatory Elements and Wording of Licence Notices ^ top

Creative Commons licensed content may only be used and shared under specific conditions. These conditions are clearly defined in the chosen licence - and must be respected and transparently documented by users for every reuse.

To make this process as easy and consistent as possible, Creative Commons recommends the so-called T.A.S.L. principle as a mnemonic for the required citation elements:

| Memory Aid | Explanation |

|---|---|

| T | Title of the work (if possible with link to the work) and year of publication |

| A | Name of the Author(s), creator(s), or rightsholder(s) |

| S | Source: Direct link to the source or publication page |

| L | Full Licence reference including a link to the licence description |

If the content has been adapted, translated, or shortened, a corresponding modification notice is mandatory - for example:

- "shortened"

- "translated"

- "content adapted"

- "combined with own material"

Example of a complete licence notice: ^ top

Copyright, Plagiarism & AI © 2025 by Christian H. Huber is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

If the material has been edited - for example, through structural or content modifications or through graphical and other changes - this must be made transparent:

Based on Copyright, Plagiarism & AI © 2025 by Christian H. Huber is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Content adapted by Fachochschule Kufstein Tirol - University of Applied Sciences -, 2025. Didactic revision and visual enhancements by Bente Morgen, 2025.

Different Wording and Placement Depending on the Medium ^ top

The wording and placement of licence notices may vary depending on the medium - but the content of the citation (T.A.S.L.) remains the same.

| Medium | Recommended Implementation | Example Formulation |

|---|---|---|

| Text document | Full T.A.S.L. reference in a footnote or bibliography; at minimum including author name, title, licence type + link, URL of the original source. | Copyright, Plagiarism & AI © 2025 by Christian H. Huber, licensed under CC BY 4.0, https://melearning.online/compendium/de/base/copyright. |

| Presentation | Short version on each used slide | © 2025 Christian H. Huber, CC BY 4.0 |

| Video | T.A.S.L. in end credits, video description or overlay; for longer videos, ideally shown at the beginning and end. | Contains content from Copyright, Plagiarism & AI © 2025 Christian H. Huber, CC BY 4.0, https://melearning.online/compendium/de/base/copyright. |

| Podcast / Audio | Licence notice in the spoken outro or in the show notes (ideally with clickable licence URL). | Extract from Copyright, Plagiarism & AI, © 2025 Christian H. Huber, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Version 4.0, Source link: https://melearning.online/compendium. |

| Image / Graphic / Infographic | Licence reference as a caption, small text box in the image, or in metadata (EXIF, IPTC); for print use, included in the image credits. | © 2025 Christian H. Huber, Copyright, Plagiarism & AI, CC BY 4.0, https://melearning.online/compendium/de/base/copyright. |

| Website / Moodle course / Learning platform | T.A.S.L. notice for each CC-licensed work or summarised in the imprint/licence section; all links should be clickable. | Content based on: Copyright, Plagiarism & AI, © 2025 by Christian H. Huber, licensed under CC BY 4.0. |

Additional Metadata ^ top

In addition to the required information, it is advisable to include further metadata. These extended details improve the reuse, visibility and documentation of Open Educational Resources (OER) and academic content.

Purpose and benefits of additional metadata:

- Improves machine readability and discoverability

- Increases transparency about creation, editing, versioning and usage context

- Promotes long-term reusability - especially in collaborative projects or Open Science contexts

Recommended Additional Metadata for CC-Licensed Works

| Metadata | Description | Example for the work "Copyright, Plagiarism & AI" |

|---|---|---|

| Version / Date | Indicates when the work was created or last edited; important for multiple versions or OER developments. | Version 1.2, as of: 06.08.2025 |

| Edited by | Complements the T.A.S.L. scheme in the case of multiple contributors or editorial changes. | Edited by FH Kufstein Tirol (2025), didactic revision by Alex Morgan (2025) |

| Context of Use | Documents the intended purpose or learning context for which the work was created or adapted. | Created for the module "Academic Writing" in the MA Energy & Sustainability Management |

| Licensing Link (machine-readable) | Allows machine-readable embedding, e.g. in HTML, CMS or repositories. | <a rel="license" href="https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/">CC BY 4.0</a> |

| Keywords / Tags | Helps content discovery; multiple tags possible. | OER, Copyright, Creative Commons, Academic Writing, Higher Education |

| Language / Translations | Language of the original version and available translations or multilingual versions. | Original: German; Translation into English by FH Kufstein Tirol, 2025 |

| Third-Party Sources / Images | Separate references are required for embedded materials with their own licences. | Infographic "Types of Plagiarism": Pixabay, CC0, via https://pixabay.com |

3.1.3 Avoiding Mistakes ^ top

Creative Commons licences enable the legal use and sharing of content - but only if applied correctly. Incomplete or incorrect licence information not only risks invalidating the legal use, but also contradicts the principles of openness and transparency.

| Error Type | Description | Concrete Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Information | Only the license (e.g. "CC BY") is given, but no source or author mentioned. | Licensing not documented properly; possible violation of license terms. |

| Missing License Link | The license (e.g. CC BY 4.0) is mentioned but not linked to the official CC website. | No proof of licensing terms for third parties; possible legal violation. |

| Unclear Edits | No information on whether the material was edited or by whom. | Violation of transparency requirements, especially for CC BY-SA. |

| Mixing Incompatible Licenses | CC-licensed work is combined with incompatible licenses (e.g. CC BY-SA and NC). | Breach of share-alike conditions (SA); potential legal conflicts. |

| Misinterpretation of NC Clause | Content is used in contexts considered "non-commercial" without verification. | Risk of legal warnings when used on ad-financed platforms or paid course systems. |

Checklist ^ top

Creative Commons licensed works may be used under clear conditions - but only if applied properly. Use this checklist to verify the main requirements:

3.2 Open Educational Resources (OER) ^ top