Literature Search & Identifying Fake News

conducting academic searches - finding relevant sources

Summary [made with AI]

Note: This summary was produced with AI support, then reviewed and approved.

- Literature research is the foundation of academic work. It helps to systematically identify existing studies, evaluate them critically, and place them within a theoretical framework. This anchors your own work in the academic discourse.

- The purpose of literature research goes beyond collecting sources. It sharpens the research question, supports methodological decisions, and ensures that results are transparent and comparable.

- Depending on the stage of the project, literature work serves different functions - from finding a topic and defining theoretical boundaries to analysis and discussion.

- Fake news, misinformation, and satire require critical evaluation. Important aspects include traceability, context, reliability of sources, and methodological quality. Analytical frameworks such as the CRAAP Test can be helpful for this purpose.

- Criteria for evaluation include the credibility of the source, editorial context, comparison with other sources, plausibility of arguments, and the authenticity of visual media.

- International fact-checking networks and national initiatives provide useful tools for verifying information.

- Methods of literature research include snowballing and systematic searching. Snowballing uses backward and forward references, while systematic searching relies on clear search strings and defined databases. In practice, a combination of both is recommended.

- Systematic reviews follow a clear process - from search strategy and screening to analysis and structuring. Documentation and transparency are essential throughout the process.

- Different research tools vary in suitability. General search engines or large language models are methodologically unsuitable, while academic databases and specialised tools such as Semantic Scholar or Scite better meet quality standards.

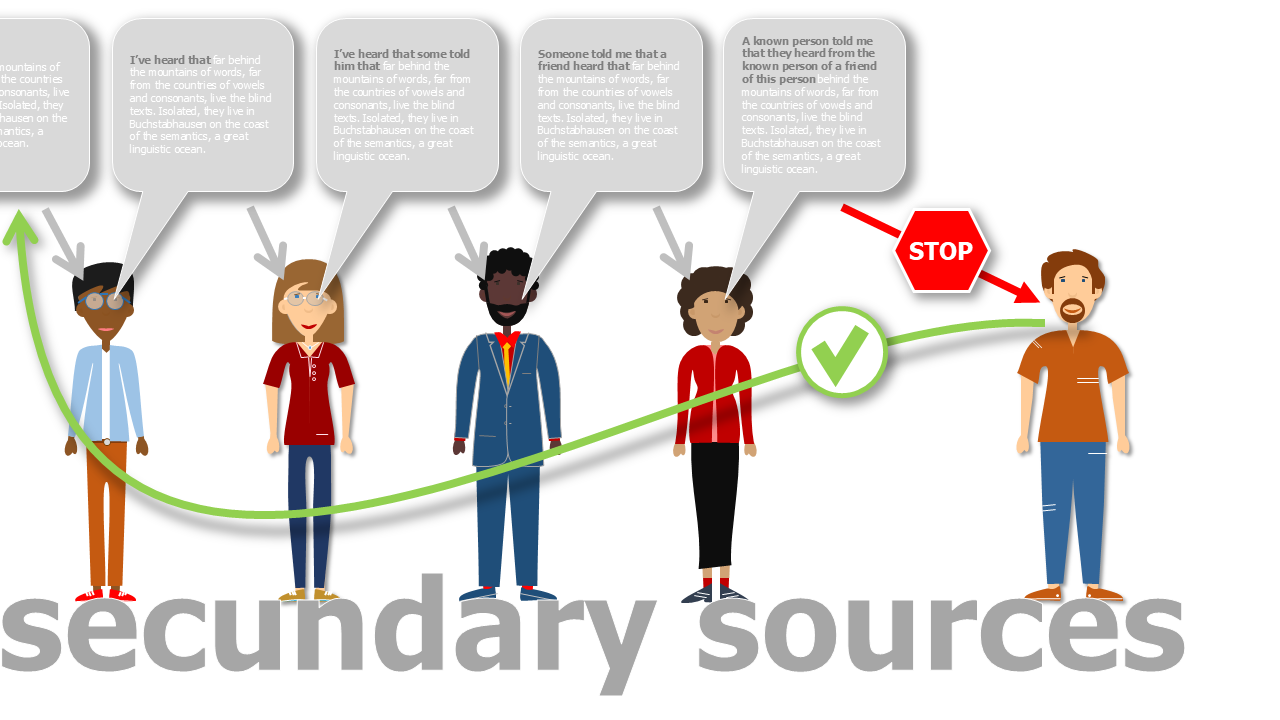

- The quality of academic work depends on selecting appropriate types of sources. Primary sources should be preferred, while secondary sources should only be used in exceptional cases. Wikipedia can be helpful for orientation but should not be cited directly.

- Evaluation criteria for academic sources include independence, objectivity, transparency, reliability, timeliness, relevance, quality, and adherence to ethical standards.

Topics & Content

- 1. Literature Search

- 1.2 Purpose, Role and Relevance of Literature Search in Academic Work

- Reflection Task / Activity

- 1.3 Hoaxes, Fake News and False Information

- 1.3.1 Distinguishing Satire, Misinformation and Disinformation

- 1.3.2 Spotting False Information - Criteria for Critical Evaluation

- Further Reading / Resources

- 1.3.3 No Fake News - Information Sites & Tools for Identifying False Content

- International Fact-Checking Networks

- Austrian & German Initiatives

- Tools for Verifying Visual and Audiovisual Content

- Educational Networks & Resources

- Reflection Task / Activity

- 2. Methods of Literature Search

- 2.1 Snowballing vs. Systematic Literature Search

- Further reading on snowballing

- Systematic review examples

- 2.2 Advantages and Disadvantages of Both Methods

- 2.3 Steps of a Systematic Literature Review

- 2.3.1 Define Search Strategy - Terms and Parameters

- 2.3.2 Conduct Search and Screen Results

- 2.3.3 Analyse and Structure the Literature

- Reflection Task / Activity

- 3. Search Tools and Platforms

- 3.1 General Search Engines - Not Suitable for Academic Research

- 3.2 LLMs - Not Suitable for Academic Literature Search

- 3.3 Google Scholar - Limited Usefulness

- 3.4 Wikipedia as a First Source of Information

- Exceptions: When Wikipedia Can Be Cited

- Reflection Task / Activity

- 3.4 Academic Databases - Core Tools for Scholarly Research

- Key Subscription-Based Databases (accessible via Fachochschule Kufstein Tirol - University of Applied Sciences -)

- 3.5 Open Access Databases - Freely Accessible Scholarly Resources

- 3.6 Platforms by and for Researchers

- Reflection Task / Activity

- 4. Types of Sources and How to Evaluate Them

- 4.1 Primary and Secondary Sources

- 4.2 Criteria for Academically Suitable Sources

- 4.3 Sources for Academic Work

- 4.4 Checklist for Assessing Scientific Quality of Sources

- Reflection Task / Activity

1. Literature Search ^ top

Academic work is not based on opinions or everyday experiences, but on verifiable and well-documented knowledge. A critical engagement with relevant academic literature forms the foundation of this knowledge. Therefore, literature search is not a secondary step but a central element of any academic project - whether it's a presentation, seminar paper, bachelor's or master's thesis.

The goal of literature search is to identify, contextualise and critically assess the existing state of research on a specific topic or question. It provides the theoretical foundation that your own work builds on - whether to further develop existing models, identify research gaps or empirically examine established hypotheses.

Engaging with literature is always a process of orientation within the academic discourse. By researching and analysing relevant sources, you gain insight into which topics have been extensively studied, which concepts and terminologies are used in the field, and where further clarification is needed. These insights are crucial for sharpening your research question and planning your methodological appro

1.2 Purpose, Role and Relevance of Literature Search in Academic Work ^ top

Academic writing does not occur in a vacuum. It always forms part of a broader research context - whether by building on existing theories, refining current models or critically engaging with recent studies. In this context, literature search fulfils a vital function: it positions your own work within the academic discourse and reveals what is already known, which questions remain unanswered and how your own contribution fits into this landscape.

The purpose of literature search is not merely to "collect sources". Rather, it involves systematically identifying, critically analysing and theoretically situating relevant academic literature. This is the only way to develop a well-founded line of argument and formulate a precise research question. A solid literature base also supports methodological decisions, helps derive hypotheses, or justifies case selections in a transparent manner.

The role of literature research shifts depending on the phase of your project:

- In the topic-finding phase, it helps identify promising research gaps or socially relevant issues.

- During conceptual planning, it aids in defining theoretical terms, comparing models or mapping academic schools of thought.

- In the analysis phase, it allows you to contextualise results and compare them with existing studies.

- In the discussion, it supports a critical reflection on the reach and limitations of your findings.

Careful engagement with literature increases not only the academic quality but also the credibility of your work. Readers quickly recognise whether a topic has been thoroughly researched, whether the state of research has been accurately represented, and whether arguments are based on sound evidence. Literature search is not an optional add-on - it is the backbone of any academic argument.

This is especially true in practice-oriented degree programmes such as Energy & Sustainability Management or Facility Management & Real Estate. In these fields, literature research is key to effectively linking theory and practice. Relying solely on practice reports, personal observations or popular science articles can lead to methodological and substantive weaknesses. Academic rigour begins with a precise, traceable and theory-driven literature analysis - and that requires both methodological skills and critical thinking.

Reflection Task / Activity ^ top

Choose two academic papers, ideally from your field of study. Read both papers with a focus on how they use literature:

How many and what types of sources are used? What purposes do these sources serve (e.g. defining terms, building theoretical frameworks, selecting methods, comparing findings)? Highlight specific places in the text where literature is cited.

Then ask yourself: What would be missing if this source were not included? Is its use appropriate and logical? Take notes on the role of literature in different sections of the paper (introduction, theory, method, analysis, discussion).

Based on your analysis, define what you want to pay particular attention to in your next project: When will you start searching for literature? What approach will you take to find relevant sources and use them effectively?1.3 Hoaxes, Fake News and False Information ^ top

False information has accompanied human history for centuries - but with the rise of digital media, its speed, reach and impact have drastically increased. Content can now be distributed globally, shared rapidly and reproduced endlessly, often without checking its origin, intent or factual accuracy. False information may be spread deliberately - for disinformation, propaganda or product marketing - or unintentionally, due to poor research, misunderstandings or uncritical sharing.

Academic work requires the ability to critically assess information and consciously exclude problematic content. Not every unconventional source is automatically untrustworthy - just as not every professionally designed website is reliable. What matters are traceability, context, source base and methodological integrity.

1.3.1 Distinguishing Satire, Misinformation and Disinformation ^ top

Not all false information is created with intent to deceive. Misunderstandings can occur - for example, when satire is not recognised or poorly labelled. Satire is a form of expression protected by freedom of speech and artistic freedom. It may exaggerate, polarise or fictionalise without claiming factual accuracy. It only becomes problematic when satirical content is mistaken for fact or taken out of context.

Types of problematic content:

| Type of Message | Description |

|---|---|

| fully fabricated | Content is completely made up to provoke reactions - e.g. for scandal, opinion manipulation or defamation. Also used to promote untrustworthy products or websites. |

| partially false | The core of the information is true, but key facts are omitted, twisted or invented. This leads to distorted statements or false conclusions. |

| misunderstood satire | Satiric content that is perceived as fact due to lack of labelling or missing context. Legally not false information, but can be misleading in practice. |

1.3.2 Spotting False Information - Criteria for Critical Evaluation ^ top

Every day, countless pieces of information circulate online, many of which are difficult to verify. The critical evaluation of texts, images, statements and sources is therefore a core academic skill. Disinformation and manipulation are not always easy to detect, as they are often professionally designed and deliberately obscure doubts.

The following areas of analysis provide a structured framework for evaluating information sources using the CRAAP test principles: Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose.

-

Source Evaluation - Check formal and content-related credibility

- Is there an imprint or bibliographic information?

- Are author(s) and publisher(s) named?

- Are academic qualifications or institutional affiliations identifiable?

- Was the content published by a recognised institution, academic publisher or journal?

- Is the language neutral and objective, or emotional and sensational?

- Are official domains and institutional names used correctly (e.g. "who.int" not "who-int.org")?

- Is there reference to established scholarly discourse?

-

Contextual Analysis - Understand intent and rhetoric

- Is there a clear political, ideological or commercial agenda?

- Are key narratives repeated to promote a particular viewpoint?

- Use of emotionally charged terms (e.g. "mainstream media lies", "hidden truth", "secret document")?

- Are opposing views or nuanced perspectives omitted?

- Is there a lack of editorial structure or publishing conventions?

-

Cross-Referencing and Plausibility - Assess content

- Are statements supported or contradicted by credible sources?

- Are quotes complete, accurate and verifiable in context?

- Do the mentioned persons or institutions actually exist - and are they credible?

- Can data, statistics or studies be traced back to sources?

- Is the argument coherent, logical and free of contradictions?

-

Visual Media - Assess image and video authenticity

- Use reverse image search to check original image context

- Look for signs of digital editing (artefacts, shadows, blurring, unnatural effects)

- Analyse metadata if available (date, location, file info)

- Watch for selective cropping or zooming that removes contextual elements

-

Evaluate Before Using or Sharing - Reflect on responsibility

- Fact-check before sharing in conversations, presentations or on social media

- Be sceptical of "too perfect" or overly dramatic content

- Apply extra scrutiny to emotionally charged topics (fear, outrage, insecurity)

- Be aware of your own cognitive biases (confirmation bias, wishful thinking)

- Refrain from passing on unchecked information - even if you personally agree with it

Further Reading / Resources ^ top

-

Evaluating Information - Applying the CRAAP Test © 17.09.2010 by Sarah Blakeslee, Meriam Library, California State University, Chico, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

-

Blakeslee, S. (2024). The CRAAP Test. LOEX Quarterly, 31(3), 6-7. https://commons.emich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1009&context=loexquarterly

1.3.3 No Fake News - Information Sites & Tools for Identifying False Content ^ top

This list of international platforms and tools can help verify information, images and videos. These resources promote media literacy and enable informed evaluation of content from different regions. The list is exemplary, not exhaustive.

International Fact-Checking Networks ^ top

-

International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) - global network promoting quality standards for fact-checkers, including a code of principles for independence and transparency.

-

European Fact-Checking Standards Network (EFCSN) - alliance of European fact-checking organisations committed to shared quality standards.

-

Reuters Fact Check - fact-checking unit of a global news agency with defined evaluation criteria.

-

Africa Check - independent fact-checking organisation based in Johannesburg, active in multiple African countries in English and French.

Austrian & German Initiatives ^ top

-

Correctiv - Faktencheck - independent German investigative platform publishing regular fact-checks on political claims, viral social media posts and fake news.

-

DPA-Faktencheck - fact-checking unit of the German Press Agency, analysing social media content for accuracy.

-

ARD Faktenfinder - fact-checking section of public television, analysing news stories and disinformation campaigns.

-

HOAXmap - interactive collection of false reports, especially those related to migration, including fact-based rebuttals from credible sources.

-

Faktenforum - structured fact collections on topics such as climate, energy, vaccines, migration or economics.

-

Mimikama - Austrian platform raising awareness on internet misuse, social media hoaxes, scams and chain messages. Offers its own investigations and explanatory content.

Tools for Verifying Visual and Audiovisual Content ^ top

-

YouTube DataViewer (Amnesty International) - tool to verify video upload data and track content origins.

-

Google Images - tool for reverse image search to check the origin and context of visuals.

-

TinEye - reverse image search tool to verify visual content.

Educational Networks & Resources ^ top

-

Trust Project - develops "Trust Indicators" to help users identify reliable journalistic content.

-

[Center for an Informed Public] - offers educational materials for countering global disinformation.

-

First Draft News - formerly a global network with training, tools and resources on disinformation, now continued on new platforms.

-

News Literacy Project - US-based educational initiative offering digital tools and teaching materials to promote news literacy.

Reflection Task / Activity ^ top

Find two online articles on a current topic in your field of study. Choose one from a recognised academic source and one from a public blog, social media platform or video channel.

Evaluate both using the following criteria: Who is the author? Is there evidence of their qualifications and credibility? Are sources cited? Are they traceable and verifiable? Is the language sensationalist or manipulative? Are facts and opinions clearly separated? Use at least one of the tools or strategies mentioned (e.g. reverse image search, fact-checking site, comparison with official source).

Finally, reflect: Which article would you use for academic work - and why? Which indicators were particularly helpful for your assessment? How confident do you feel in handling questionable sources?2. Methods of Literature Search ^ top

A precise and systematically conducted literature search is a key component of any academic project. It provides the foundation for theoretical argumentation, supports critical engagement with existing knowledge and enables the development of original research questions. The aim is not to collect as many sources as possible, but to identify relevant, credible and up-to-date literature, evaluate it critically, and integrate it meaningfully into the structure of the argument.

There are two established methods of literature search, each with its own strengths and limitations: the snowballing technique and the systematic literature search. These methods can be combined and should always be documented transparently.

2.1 Snowballing vs. Systematic Literature Search ^ top

Snowballing starts from a small number of key sources and builds a network of related literature by tracking references (backward search) and identifying newer publications that cite the source (forward search). This method is useful for initial orientation or niche topics with limited database coverage.

A systematic literature search follows a structured, documented and reproducible approach. Based on a research question, keywords are defined and applied in recognised academic databases. The results are screened and selected based on clear and transparent criteria. This method allows for a comprehensive and traceable review of the current state of research.

| Approach | Snowballing | Systematic Literature Search |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Select relevant seed sources | Define keywords from the research question |

| Search Strategy | Backward: track reference lists Forward: find citing publications |

Use search terms in scientific databases, filter by relevance |

| When to Stop? | When no new relevant sources are found | When all results have been reviewed |

Further reading on snowballing ^ top

- Wohlin, C. (2014). Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1145/2601248.2601268

Systematic review examples ^ top

-

Madanayake, U. H., & Egbu, C. (2019). Critical analysis for big data studies in construction: Significant gaps in knowledge. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 9(4), 530-547. https://doi.org/10.1108/bepam-04-2018-0074

-

Xu, J., Chen, K., Zetkulic, A. E., Xue, F., Lu, W., & Niu, Y. (2019). Pervasive sensing technologies for facility management: A critical review. Facilities, 38(1/2), 161-180. https://doi.org/10.1108/f-02-2019-0024

-

Jabeen, S. et al. (2020). A Comparative Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis on Sustainability of Renewable Energy Sources. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 11(1), 270-280. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijeep.10759

-

Huber, C., Koch, D., & Busko, S. (2014). An International Comparison of User Satisfaction in Buildings from the Perspective of Facility Management. International Journal of Facility Management, 5(2).

2.2 Advantages and Disadvantages of Both Methods ^ top

No method is universally superior - depending on the topic, research aim and availability of literature, one approach may be more suitable than the other. In practice, a combination of both is often most effective: start with a systematic database search, then extend the results through targeted snowballing.

| Criterion | Snowballing | Systematic Literature Search |

|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | Often high, especially with open-access seed sources | Often low - many articles behind paywalls |

| Credibility | High if seed source is academically sound | Needs to be assessed in each case |

| Diversity of Results | Often low, especially with homogeneous sources | High - shows various approaches and perspectives |

| Time Requirement | Quick at first, but time increases with each step | High initial effort for planning and documentation |

| Risk of Irrelevant Sources | High if the seed source is inadequate | High if keywords or filters are poorly chosen |

| Best Use | For initial overview and topic exploration | For systematic analysis and overviews |

2.3 Steps of a Systematic Literature Review ^ top

A systematic literature review is a methodologically controlled process for identifying, selecting, analysing and evaluating academic sources. Its aim is to gather relevant literature in a structured and transparent way to provide a solid foundation for theoretical argumentation, research questions and discussion of results.

Unlike informal web browsing, a systematic review is based on fixed criteria, clearly documented procedures, and reproducibility. This improves the quality of the literature base and supports research integrity.

The process consists of three interlinked steps:

2.3.1 Define Search Strategy - Terms and Parameters ^ top

Start by deriving keywords from your research question. These should reflect all major dimensions - topic, target group, geographic or temporal aspects, and methodological approach.

Expand keywords:

- Synonyms, related terms, common abbreviations

- Broader and narrower terms

- English translations (for international databases)

From these, construct a search string using Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) to target results more precisely.

Example:

("sustainable real estate" OR "green building") AND ("user satisfaction" OR "occupant perception") AND NOT ("residential")

Define additional search parameters:

- Databases (e.g. Emerald Insight, EBSCO, SpringerLink)

- Time frame (e.g. since 2015)

- Document type (e.g. peer-reviewed journals only)

- Language

All steps must be documented for transparency in the methodology chapter.

2.3.2 Conduct Search and Screen Results ^ top

Use the search string in selected databases. Apply filters for full text, document type or discipline as needed.

Screen results in stages:

- Title screening - exclude irrelevant titles

- Abstract screening - for unclear or borderline hits

- Full-text screening - for clearly relevant studies

Apply inclusion/exclusion criteria consistently and justify exclusions. Typical exclusion reasons:

- No clear link to research question

- Not scholarly

- Full text not accessible

- Duplicates

Track progress quantitatively, e.g.:

- Number of hits per database

- Number after title/abstract screening

- Final number of included sources

Optionally, create a flowchart from initial hits to final sample - this improves transparency and aligns with best practices.

2.3.3 Analyse and Structure the Literature ^ top

Finally, analyse the selected sources, compare them, and organise them thematically. Aim to outline the current state of research, identify major positions, controversies and gaps, and explain their relevance to your own study.

Common evaluation criteria:

- Topic and aim of the publication

- Theories and models used

- Research methods (qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods)

- Samples and contexts (region, sector, target group)

- Key findings, arguments and conclusions

You can group the literature into thematic clusters or comparison matrices - by method, region, time period or argument. These clusters can also guide the structure of your theoretical and analytical sections.

Use reference management software (e.g. Zotero, Citavi) to organise, tag and comment on literature, manage citations and store abstracts and notes.

Also consider quality assessment of the literature. Evaluate sources for scholarly rigour, peer review, transparency of methods or recency. This reduces the inclusion of low-quality materials.

A thorough and well-documented literature review is essential for the credibility and traceability of your academic argument. It also strengthens your ability to reflect critically on existing research and develop original insights.

Reflection Task / Activity ^ top

Based on your current research question, define suitable keywords and create a specific search string for an academic database.

Conduct a combined search: begin with a systematic search, followed by targeted snowballing.

Document your process: Which sources did you include or exclude - and why?

Create an overview (e.g. table or cluster map) showing key similarities, differences and research gaps.

Reflect: What kind of results did each method produce? What would you do differently in your next literature search?3. Search Tools and Platforms ^ top

The quality of an academic paper strongly depends on the quality of the literature sources used. It is therefore essential to select appropriate tools and platforms to locate valid, citable and verifiable information. This chapter introduces various types of search systems - ranging from general search engines to specialised academic platforms and licensed databases.

3.1 General Search Engines - Not Suitable for Academic Research ^ top

General-purpose search engines such as DuckDuckGo, Ecosia, Qwant, Google or Bing are designed for everyday information retrieval in personal or professional contexts - not for academic purposes. Their underlying algorithms prioritise results based on commercial interests, user behaviour and technical parameters rather than academic relevance or content quality.

A major issue is the personalisation of results: these engines produce individualised lists that vary depending on location, language settings, device type, search history and user interactions. Even when identical search terms are used, the results can differ significantly - a factor that contradicts the principles of reproducibility and intersubjective verifiability in academic work.

Moreover, the ranking algorithms are neither publicly accessible nor transparently documented. The exact weighting of factors such as click-through rates, dwell time, backlinks, site structure, paid advertising or machine learning remains proprietary and opaque. This lack of transparency makes methodologically controlled literature searches extremely difficult and violates academic principles such as traceability and openness.

In addition, commercial content is often not clearly marked. Paid advertisements and SEO-optimised content frequently appear on equal footing with credible sources - or even higher. Without careful analysis, users may struggle to determine whether a source is academically sound, objective and suitable for citation.

There are also considerable uncertainties regarding content origin and subject classification. General search engines display results from a wide range of sources - from personal blogs and forums to company websites, journalistic outlets and pseudo-academic platforms. It is not possible to systematically limit results to peer-reviewed articles, reputable academic journals or official institutional publications.

Furthermore, transparent filtering, thematic classification, and documented research steps - all essential for academically sound literature searches - are lacking. Features such as Boolean search logic, restriction to specific academic journals, or access to bibliographic metadata are either very limited or entirely unavailable.

3.2 LLMs - Not Suitable for Academic Literature Search ^ top

Large Language Models (LLMs) such as Mistral, ChatGPT, Claude or Gemini can be useful tools in academic contexts - for example, in structuring ideas, generating content drafts or improving language. However, they are not suitable for conducting academically sound literature searches, as they fail to meet essential criteria for transparency, reproducibility and quality assurance.

-

No systematic search logic

LLMs do not conduct real searches. Instead, they generate text based on statistical probabilities within their training data. They do not document search strategies, apply filters or select sources methodically. A traceable search using Boolean logic, database queries or bibliographic control is not possible. -

Intransparent origins and unreliable citations

The data used in training LLMs is not publicly disclosed. Literature references may be fabricated ("hallucinated"), incomplete or incorrect. There is no verifiable origin, nor are references reliably citable. LLMs also cannot distinguish reliably between scholarly and non-scholarly sources. -

No access to validated academic sources

Standard models lack access to scholarly databases, library catalogues or domain-specific repositories. Even with plugins or APIs, it remains unclear whether retrieved texts are peer-reviewed, complete or academically relevant. They are therefore disconnected from verified, citable literature. -

No academic quality assessment

LLMs cannot assess methodological rigour, levels of evidence or relevance to specific academic disciplines. They often fail to differentiate between conference proceedings, academic articles, blogs or marketing texts. Critical appraisal of sources is missing. -

Lack of up-to-date information and version control

LLMs are trained on static datasets with a fixed cut-off date. Recent research or current publications are absent. As there is no time stamp or version history attached to outputs, users cannot determine the temporal validity of information - an issue for citation and relevance.

Unlike general-purpose LLMs, specialised AI research tools have been developed for academic use. These include platforms such as SciSpace, Consensus, Elicit, Scite or Semantic Scholar. These tools draw from academic databases, are partially linked to peer-reviewed journals and are trained on domain-specific scientific corpora.

They offer advantages in navigating academic fields, such as:

- Thematic clustering and semantic similarity analysis

- AI-generated summaries of research papers

- Automatic extraction of hypotheses, methods or findings

- Visualisation of citation networks and source relationships

In contrast to general LLMs, these tools are based on documented and traceable sources. Some offer direct links to full texts or provide full bibliographic references for proper citation. Nonetheless, users should remain critical when using these tools:

-

Content still requires verification

Even when a tool accesses academic sources, this does not guarantee that the extracted content is accurate or contextually appropriate. AI interpretations may be incomplete, misleading or decontextualised. -

Limited data coverage

Many systems rely on a restricted pool of open-access articles or selected journals. Full access to all academic publications - especially paywalled content - is not ensured. -

Unclear update cycles and database scope

The recency of data varies. It is not always clear which journals are indexed, how frequently they are updated, or whether retractions and corrections are taken into account. -

Insufficient documentation of search paths

Results are based on internal algorithms that are not fully transparent. Search strategies cannot always be documented or reproduced.

| Aspect | LLMs | Specialised AI Research Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | General-purpose models supporting various tasks like text generation, translation, editing or programming. | Designed specifically for academic research - focusing on discovering, summarising and comparing scientific studies. |

| Use Case | Useful for brainstorming, structuring, language refinement or explaining academic content. | Designed to support academic research questions, identify relevant studies, compare methods and synthesise findings. |

| Data Source | Trained on large text corpora from books, websites and open sources - no targeted academic database integration. | Built on structured scientific databases, often with live access to academic content. |

| Source Transparency | Outputs are based on language patterns, not traceable references. | Outputs are linked to DOIs, titles, authors and journals - fully citable. |

| Up-to-dateness | Knowledge is limited to the model’s training cut-off date. | Tools may provide access to recent publications depending on the platform. |

| Response Type | Answers are fluently generated but may include hallucinated facts. | Answers are evidence-based, drawn from existing studies or meta-analyses. |

| Search Function | No real database search possible; no filtering or bibliographic access. | Systematic searching by keyword, topic or question, sometimes including relevance ranking. |

| Citability | Outputs are not reliably verifiable or citable. | Studies include full citation data and can be used directly in academic writing. |

| Analytical Features | No data-driven evaluation - relies on pattern-based language generation. | Focuses on verifiable data from methods, results and samples. |

| Use in Academic Work | Helpful for drafting, outlining or understanding - not suitable for citation or literature search. | Suitable for systematic searches, summaries, source evaluation and verifying academic evidence. |

| Cost & Access Limits | Free LLM versions allow unlimited chats, but lack database integration. | Free versions provide only few results; paid plans often show abstracts only, not full texts (due to paywalls). |

| Cautions for Academic Use | LLMs may hallucinate, present outdated or factually incorrect content - critical evaluation is essential. | Even specialised tools often summarise abstracts only and may miss contextual factors - full text access via libraries remains essential. |

3.3 Google Scholar - Limited Usefulness ^ top

Google Scholar is a freely accessible search engine for academic-oriented literature. Operated by Google LLC, it automatically indexes publicly available online content, including journal articles, conference papers, theses, academic reports, technical documentation, preprints, e-books, presentation slides, and grey literature. Institutional repositories, publisher platforms and personal websites of researchers may also be included.

Google Scholar’s strength lies in its broad access to a variety of content types. It can be helpful for initial orientation and for identifying keywords, authors, highly cited works or foundational debates. The "Cited by" feature is also useful for discovering related literature or analysing backward citations.

However, Google Scholar is only partially suitable for systematic academic literature research. This is due to several limitations:

-

Intransparent indexing

It is unclear which sources are indexed and which are not. Google does not provide a comprehensive list of its partner databases or publishers. The currency of the indexing is also not verifiable. As a result, there is no guarantee that relevant academic articles are included in the search results. -

Opaque ranking system

The ordering of results is based not only on keyword relevance, but also on citation frequency, author profiles or internal relevance metrics. The exact algorithms are not disclosed, which can distort the ranking. New or less-cited, yet high-quality publications may be ranked lower. -

Lack of quality control

Google Scholar does not clearly distinguish between peer-reviewed journal articles and non-reviewed literature. Preprints, unpublished manuscripts or automated translations may appear without clear indication of their academic status. This complicates the assessment of citation suitability and scholarly quality. -

Frequent duplicates and outdated versions

The same article may appear in several versions - e.g. as a preprint, as a PDF on an author’s website, and as the final publisher version. The results list often includes outdated or incomplete versions without clear labelling. This redundancy makes it difficult to select the correct and citable version. -

Unclear traceability and missing metadata

Many entries lack complete bibliographic details. Editors, journal names, publication years or DOIs may be missing or incorrectly recorded. This poses challenges for precise citation and quality assessment. -

Limited filtering options

Compared to professional academic databases, Google Scholar offers only basic filters (e.g. by date or language), no thesaurus-supported search, and no filters for publication type or peer-review status. This limits the effectiveness and accuracy of academic searches.

3.4 Wikipedia as a First Source of Information ^ top

Wikipedia is an open online encyclopaedia created and continuously edited by a global community of voluntary contributors. It offers vast thematic coverage and quick accessibility, making it a popular entry point for research. Even in academic practice, Wikipedia can serve as a helpful source for initial orientation.

Wikipedia is particularly useful for:

- gaining a first overview of a topic,

- clarifying basic concepts and terminology,

- understanding thematic relationships,

- identifying keywords for further research,

- discovering further reading listed in the reference section of an entry.

Many articles include references to external academic sources, standard works or recent scholarly publications. These may be usable in academic work - provided their quality and citation suitability are verified. In addition, Wikipedia’s categories and internal links offer a clear thematic structure and help identify related terms and concepts.

Despite its broad scope and user-friendliness, Wikipedia does not meet the key standards of academic sources:

-

Authorship is often anonymous or pseudonymous, making it difficult to assess academic expertise.

-

Article edits can be made in real time without editorial oversight.

-

Content is not subject to formal peer review.

-

Temporary inaccuracies or biased content may appear.

As a result, Wikipedia’s reliability cannot be guaranteed at all times. It is not sufficient for substantiated argumentation or academic evidence. Therefore, it should generally not be cited directly in scholarly work.

Exceptions: When Wikipedia Can Be Cited ^ top

In specific cases, using and citing Wikipedia may be academically justifiable - for example:

- when referring to Wikipedia itself, such as its functionality or content structure,

- when quoting passages from articles with clearly identifiable authors listed in the edit history,

- when using archived versions of articles that are properly documented, versioned and permanently accessible.

To cite Wikipedia appropriately, the following conditions must be met:

-

Author transparency

The edit history of a Wikipedia article allows you to track individual contributions. If contributors use real names or verifiable user profiles, they may be named as authors. While this improves transparency, it does not replace peer review. -

Version and permalink citation

Since Wikipedia entries are constantly updated, always cite the exact version you used. This includes:- the date of the article version,

- the URL of the archived version (the "permalink" - similar to a DOI in journal articles),

- the article title and section (if applicable).

Reflection Task / Activity ^ top

Search for a Wikipedia article on a topic of academic interest to you and locate the relevant version(s) with time stamp and archived permalink.

Review the literature and web references listed in the article: Which of the linked sources are academically citable? Which meet the criteria of scholarly quality, traceability and citation suitability?

Summarise your findings in a short overview and reflect: Which of these sources could you actually use in an academic paper - and why?3.4 Academic Databases - Core Tools for Scholarly Research ^ top

Academic databases are specialised search systems that exclusively index scholarly literature. They offer structured search functions, defined filter options and transparent documentation of sources. Results are generated based on clear criteria, such as matches between search terms and titles, abstracts, keywords or full texts.

These platforms enable a controlled, systematic and traceable search process - a key quality criterion in academic work. Most databases require institutional access; not all articles are freely available in full text.

Key Subscription-Based Databases (accessible via Fachochschule Kufstein Tirol - University of Applied Sciences -) ^ top

-

EBSCO - multidisciplinary database with a wide range of journals

-

Springer Link - German- and English-language academic literature, with a strong focus on engineering, business and sustainability

-

Emerald Insight - international journals specialising in management, environment, education and real estate

3.5 Open Access Databases - Freely Accessible Scholarly Resources ^ top

Open-access platforms provide free access to academic texts. They are generally not behind paywalls but vary in depth and quality. Some also include preprints - articles that have not yet undergone peer review.

-

arXiv.org - preprint archive for physics, mathematics, computer science and related fields

-

BASE - Bielefeld Academic Search Engine - multidisciplinary search engine for open-access materials

-

OpenGrey - platform for European grey literature, such as research reports, conference papers and dissertations

3.6 Platforms by and for Researchers ^ top

Academic social networks offer access to scholarly publications, preprints, conference contributions and working papers. Many authors voluntarily upload their work here.

-

ResearchGate - international platform with researcher profiles, direct contact features and, in some cases, extended data sets

-

Academia.edu - predominantly English-language platform for uploading and exchanging academic texts across disciplines

Note: Content on these platforms should be checked for formal publication status and peer review. Not all contributions are suitable for citation in the strict academic sense.

Reflection Task / Activity ^ top

Choose a specific topic from your field of study and search for it using

a) a general search engine

b) Google Scholar

c) an academic database

d) an open-access database of your choice

Compare the results in terms of relevance, source quality, search transparency and citation suitability.

Reflect: Which platform(s) were most helpful for your search? What surprised or confused you about specific platforms? Which search strategy would you prefer for your bachelor’s or master’s thesis?4. Types of Sources and How to Evaluate Them ^ top

In academic writing, precise handling of sources is essential. Different types of sources vary in their academic relevance and usability. This chapter explains how to distinguish between primary and secondary sources, what general criteria scholarly sources must fulfil, and which types of sources are suitable in which contexts.

4.1 Primary and Secondary Sources ^ top

In literature, social sciences, and in natural or technical sciences, a distinction is made between primary and secondary sources. This distinction is also relevant in academic writing, as the type of source directly affects the validity, traceability, and citation method of the information used.

| Primary Source | Secondary Source |

|---|---|

| Original source of a claim or finding | Reproduction, interpretation, or use of the primary source |

| Contains original data or texts | Refers to the content, analysis, or conclusions of the primary source |

| Requires direct reading and analysis | Can be used when the primary source is inaccessible |

| Preferred reference for direct quotations | Allows analysis of reception, development or reinterpretation |

In general, statements should be based on primary sources. Secondary sources may only be used if the primary source is unavailable or if the focus is on how a work has been received or interpreted.

4.2 Criteria for Academically Suitable Sources ^ top

Not every publicly accessible document meets the standards required for academic use. Academic work requires sources to be selected and applied based on clearly defined and verifiable quality criteria. These criteria address the content quality of a source, as well as its transparency, traceability and relevance to the research question.

The central question is whether a source provides verifiable, peer-reviewed and transferable knowledge. Scholarly sources must be critically examinable, logically coherent, and methodologically sound. They should result from a systematic process of knowledge production, remain open to critique, and contribute to the advancement of academic discourse.

The reliability of a source is particularly important - i.e. whether it can be verified repeatedly (reproducibility), whether the author(s) are clearly identifiable (authorship), and whether the content is current, relevant, and produced independently (objectivity).

| Criterion | Description | Grounds for Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Independence & Objectivity | The source does not serve a specific economic, political or ideological agenda; multiple perspectives are considered. | Advertising, lobbying, PR material, isolated opinion pieces without context |

| Scholarly Quality | The source originates from a recognised academic or research-based institution and follows academic standards (e.g. peer review). | Personal blogs, forum posts, anonymous texts, YouTube comments |

| Factual Correctness | Statements are fact-based, logically argued and free from sensational language or manipulative devices. | Emotionally charged language, absolute claims, rhetorical questions |

| Traceability | Data, sources and reasoning are fully documented; arguments are transparent and logically structured. | No methodology, missing data basis, unclear or undocumented conclusions |

| Citability | Author(s), publisher, year and place of publication are known; the document is published and accessible. | Anonymous content, unpublished documents, missing bibliographic data |

| Currency | The source is timely and appropriate for the research question; the publication date is visible. | Outdated, no publication date, unclear status |

| Relevance | The source relates directly to the research question and contributes theoretical or empirical foundations. | Off-topic, pure opinion with no scholarly framework |

| Purpose Transparency | The content serves academic knowledge rather than marketing, persuasion or commercial gain. | Promotional content, image campaigns, politically motivated publications |

4.3 Sources for Academic Work ^ top

Not all types of texts are equally suitable for academic analysis. The following table provides an overview of selected source types, their use, and their strengths and limitations in the academic context.

| Source Type | Usage | Advantage | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bachelor/Master Theses | not suitable | provide student perspectives | not peer-reviewed, possibly unverified sources |

| Doctoral Theses | suitable | published, reviewed | not always up to date |

| Conference Proceedings | suitable | current, project-based | unclear quality criteria |

| Academic Journals | highly suitable | peer-reviewed, high quality | long publishing process |

| Textbooks/Handbooks | limited use | definitions, foundational knowledge | seldom current, few sources |

| Popular Science | not suitable | simple explanations | not academically verified |

| Blogs | not suitable | current, informal | unverified, subjective |

| News Articles | context use only | wide reach, topical | lack of scientific rigour |

| Company Websites | context-specific use | current | commercial purpose |

| Independent Institutions | limited use | professionally relevant | potential bias |

4.4 Checklist for Assessing Scientific Quality of Sources ^ top

Use the following checklist to assess whether a source is scientifically sound and appropriate for academic work. The more criteria are met, the more reliable the source.

Reflection Task / Activity ^ top

Choose an academic publication of your choice and analyse which types of sources are used. Distinguish between primary and secondary sources, evaluate their citability, and reflect on whether you would include all sources in your own academic work. Justify your decision in writing.

![Creative Commons 4.0 International Licence [CC BY 4.0]](https://melearning.online/compendium/themes/simpletwo/images/meLearning/cc-by-large.png)